By JOY HINYIKIWILE

In March 2022, the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) upheld with costs the case by former Rhodes student, Yolanda Dyantyi, to appeal Rhodes University’s disciplinary case against her.

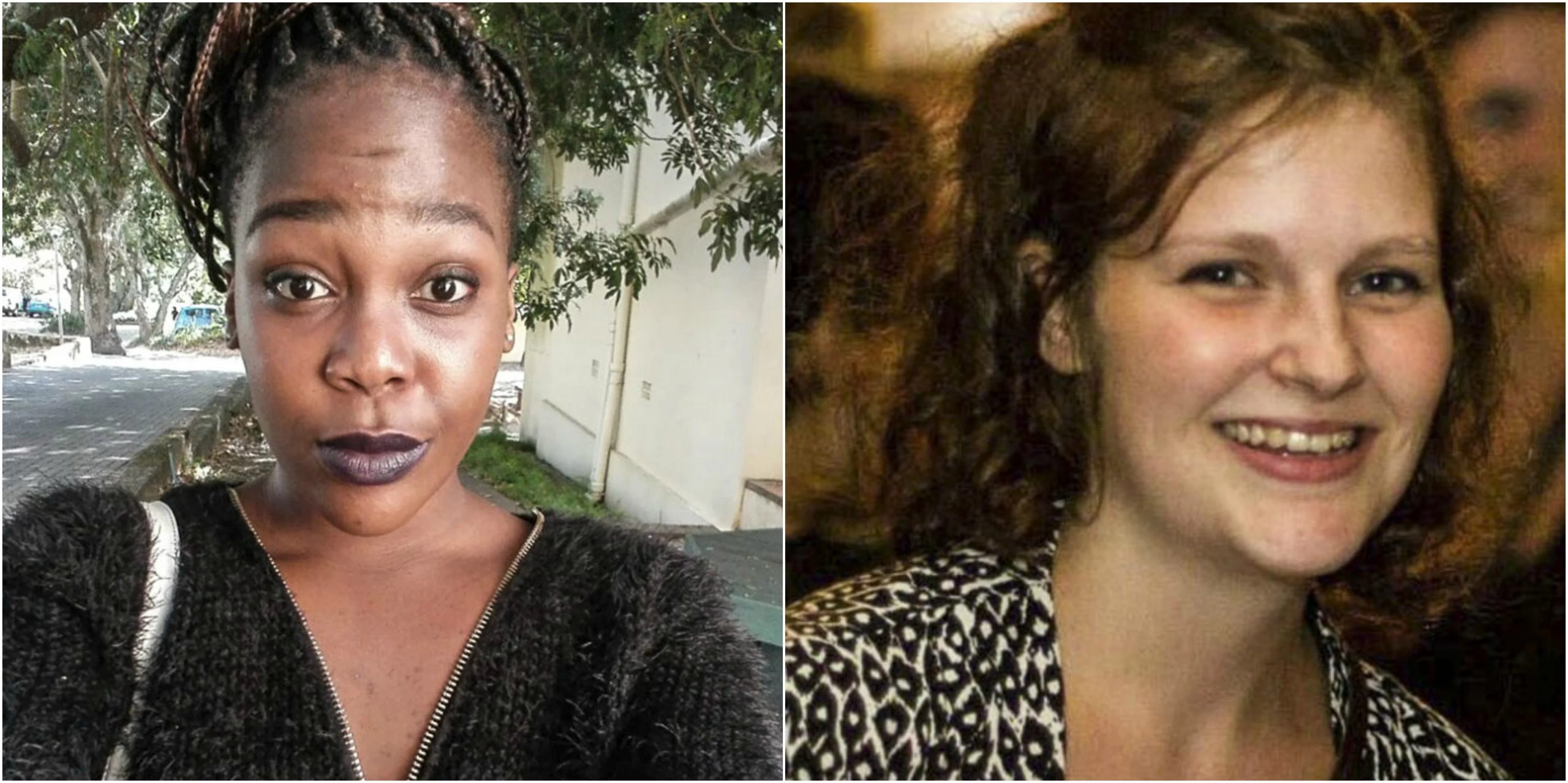

Dyantyi was permanently excluded from the university with two exams left before completing her BA degree in November 2017. Along with Dominique McFall and Naledi Mashishi, she was accused of being involved in an incident in which three male students were held against their will during the 2016 #RUReferenceList protests against sexual harassment and rape.

On 17 November 2017, the university found Dyantyi guilty of kidnapping, insubordination and assault, and McFall guilty of kidnapping and insubordination. It permanently expelled them from the university with their academic scripts endorsed, while Mashishi was expelled for ten years. However, on 29 March 2022, the SCA ordered the university to reconsider the disciplinary inquiry and that a different person chair further investigations into Dyantyi’s charges.

What happened after the #RUReferenceList protests? What message did the expulsions of McFall and Dyantyi send to students and staff about the university’s tolerance of anti-GBV activism on campus? Do students feel empowered to engage in anti-GBV activism? Has there been any progress in the fight against rape culture at the university?

Grocott’s Mail recently spoke to Dantyi, McFall and the chair of the Rhodes Sexual Violence Task Team, Prof Catriona Macleod, about the legacy of the #RUReferenceList protests to help open a dialogue on these questions. Please feel free to share your thoughts with us. And, if you don’t feel free to do so, please let us know at grocottseditor@ru.ac.za – your contributions will remain anonymous.

Dominique McFall’s story

Yolanda Dyantyi was not the only one who faced disciplinary action for her participation in the #RUReferenceList protests. Like Yolanda Dyantyi, Dominique McFall was also expelled for life for participating in the #RUReferenceList protests. She was in the final year of her BA degree when the university expelled her and refused to transfer her credit for the courses she had completed.

The university charged her with kidnapping, insubordination and acting in contravention of the student disciplinary code.

After the March SCA ruling in the case of Yolanda Dyantyi versus Rhodes University, Grocott’s asked McFall for her comment on the verdict.

McFall said she was relieved Dyantyi finally won her case at the SCA five years after they were served papers for the disciplinary hearings. She feels affirmed the SCA recognised that there was prejudice in Rhodes University’s disciplinary action.

Along with Dyantyi, McFall had initially also made court applications to challenge the university’s disciplinary action against them in 2017. They were represented by The Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI) as pro-bono clients.

McFall said she withdrew her application in 2019 because she wanted to continue studying and did not want to depend on the case outcome. She was also scared it would be a financial gamble to pursue the case and still lose.

She, however, believes there was great injustice in their expulsion, particularly Dyantyi’s, considering that she was not able to testify for herself.

“The reason I dropped the case is not at all because I [didn’t] think I’d have won. I stand by my actions on the day… and I think that the judgement by the SCA proves that [the disciplinary action]was a biased process.”

Dominique also says she stands by the witnesses who supported her and testified that she was not involved in kidnapping or insubordination. She believes there was overwhelming evidence that helped her and that the judgement by the SCA affirms her case.

“I found it very affirming to see that [the injustice]was finally recognised because it has been an arduous journey what we went through.

“The recognition was so important to me, especially when I read the judgement and that the judge said there was no reason to hurry [the disciplinary process].”

She believes the end of the disciplinary process was a “race to the deadline” to see if the hearing would finish before they finished their exams.

“It didn’t feel like it was about justice. It felt like it was about ensuring that exclusions occurred… and this is reflected in the judge’s findings.”

Though the exclusion made it difficult for her to find admission at South African universities, Dominique was able to continue her studies through a bridge university – the Open University.

“There were some incredible activists and academics who tried to assist me, particularly at UCT and UWC, where they tried very hard, and somebody else wanted to help me at Wits.

“It was just a bureaucratic decision that they could not make an exception for me despite the circumstances and [the universities]wanting me to study there as a student.”

She is currently pursuing a BA Honours in Environmental Policy and Strategic Management and is left with one assignment to complete her studies. She says she is looking to graduate finally.

McFall says she decided not to continue with the degree she had started at RU, which focused on Gender Studies.

“It’s quite disappointing that I have been made very nervous of activism and just the potential consequences of being a female activist and standing against GBV.”

She currently works for an NGO.

“I’ve been very fortunate to work with the same people for four years. I was recently moved into a research assistant role on an inspiring project with renewable energy, and I am thrilled to be working on it.

“It has been affirming that everyone I ever told this story to has given me nothing but support and believes that what happened was a great injustice.

“Hopefully, this is a chapter that we can all move on from and heal from. I look forward to seeing all of the amazing things that Yolanda does. I am very excited about my graduation.”

Though she wishes things had turned out differently, McFall says she has taken the expulsion as “a bit of a knock” and has decided to focus on moving on and rebuilding as best as possible.

“The one thing that I’ve learned and been shown throughout the process is that the true heart at Rhodes University is the lecturers, notably the Allan Grey Centre for Leadership Ethics, the Psychology Department, and the English Department.

“The head of the English Department at the time, Sue Marais, was incredible. She was so supportive and tried to fight for my exams to be marked so I could get full credit.”

McFall said she had experienced overwhelming support from colleagues, friends and activists who saw the expulsions as an injustice. Regarding the legacy of #ReferenceList protests, she said she found the subject too triggering to engage.

Yolanda Dyantyi’s story

After the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled in her favour to overturn Rhodes University’s decision to expel her for her involvement in the 2016 #RUReferenceList and Rape Culture protests, we contacted Yolanda Dyantyi and asked her about her journey in the legal battle. This is what she had to say:

“The #RUReferenceList and Rape Culture protests were just a point where students had had enough of being silenced by the university’s refusal to centre [rape]survivors’ needs and the concerns of students. We also opposed the university’s refusal to prioritise channelling resources towards establishing whatever preventative and support measures needed to be established.

“This is not to say that there were never any [GBV] measures in place, but what the protests were pointing at was that the policies were not working for us as students, and so we needed the system to transform.

“That’s why I participated in the protests. We said we could not go to school with perpetrators and bump into them in lecture halls.

“What was happening at Rhodes was not happening in isolation. South Africa is a highly violent society. The rape culture crisis that we talked about was not just at Rhodes or institutions of higher learning. It was a nationwide problem, and women were at the receiving end of the violence.

“Rape culture is a pervasive system and economic violence.

“What Rhodes did to me through the exclusion limited my economic prospects and academic career. My academic career was halted when they did not give me a fair trial concerning the allegations brought forward.

“At no point did I ever say I did not want to participate in the hearing, or did I ever say I did not want to testify.

“I sat in those proceedings for days and months and missed out on lectures whilst preparing with my lawyers. Unfortunately, on the days the university insisted it would be my turn to take a stand, my lawyers were not available. I had prepared my case with my legal counsel, but the university decided to proceed with the matter of me taking the stand without any legal counsel.”

On the legacy of the protests, Dyantyi said:

“I cannot speak of any legacy regarding the protests against rape culture. My legacy is participating in the protests and refusing to be bullied when I wasn’t given a fair trial.

“I was not involved in any criminal activity.

“The university has always wanted to shift blame and never once accepted accountability for the issues we complained about.

“There are people who have supported and encouraged me throughout this journey. My path has been a journey and a half. I can only hope people have been inspired to continue and not be deterred in their quest for justice.

“It’s not easy facing powerful people trying to silence you for holding them accountable.

“This particular encounter with the law has given me a little hope in the justice system, but that’s very biased because it’s my journey. I’m not going to say I believe in the justice system at large. I don’t believe in the justice system in South Africa, but in my case, in my particular journey, justice has been achieved, and what the way forward looks like now will only be determined as time goes on.”

Dyantyi said she was raising funds for her NPO www.archiveamabaliwethu.org.za and trying to save her academic career. She recently released a publication called African Feminist Solidarities. “[The publication] tells women’s stories of abuse on the website. That’s the kind of work I’m interested in – ensuring women’s stories are told,” she said.

Prof Catriona Macleod’s comments

Prof Catriona Macleod is a distinguished professor of psychology and SARChI Chair of Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproduction at Rhodes University. We talked to her about the state of student activism at Rhodes post the April 2016 protests.

Grocott’s Mail: Recommendations from the Sexual Violence Task Team report were presented to the Rhodes Senate and Council. Grocott’s understands that a sub-committee was set up to assess these recommendations and report back to Council? What were some of the points of disagreement between the SVTT report and the committee? Which policy was finally adopted by Council? We have a copy of the student sexual offences policy, but we assume there is a more comprehensive, overarching policy for the university?

Catriona Macleod: The Sexual Violence Task Team (SVTT) report was handed to the University in December 2016. The report was then inspected by a committee set up by the Vice-Chancellor. Senate recommended further engagement between the SVTT and this committee. After lengthy discussions, all of the SVTT recommendations were accepted by Senate and Council, bar two, which required further deliberation. I have seen the Student Sexual Offences Policy, but no larger or overarching policy. The Harassment Officer may know more about this.

GM: The #RUReferenceList protests were not only a significant moment for RU, but they were arguably also a significant moment in the national fight against GBV. What do you think is the legacy of the protests both at RU and nationally? Have we moved forward in the struggle against GBV at Rhodes – and the country – since 2016? If so, how? If not, why?

Macleod: Yes, indeed, the #RUReferencelist protests were very significant. However, it was interesting to note how these protests failed to get national traction in other higher education spaces. There were other protests, but nowhere near the level of disruption seen on this campus. This is in contrast to the #Feesmustfall protests. The question is, why? It is not because there are higher levels of sexual violence at Rhodes but instead because RU was (is) ahead of its time in terms of feminist pedagogy, which includes understanding the nuances of, and the silencing caused by rape culture.

Because of its high level of media and social media coverage, the #RUReferencelist protests formed part of (many other) advocacy and activist voices in highlighting the issue nationally, which eventually led to the publication of the National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence and Femicide. What was important and different from other initiatives is that it highlighted sexual violence on higher education campuses and led to an in-depth investigation in the form of the SVTT report (this report has been lauded as exemplary in higher education responses).

GM: What do you think of how RU handled the protests and the prosecution of students? What are your views on the battle between Yolanda Dyantyi and RU and the recent SCA ruling?

Macleod: A group of staff members opposed the interdict taken out by management in the days following the start of the protests. I was one of them. This opposition was important in establishing the right to non-violent but disruptive protests. This paper speaks to this judgement. I have not followed the case of Yolanda Dyantyi with great attention. It seemed to me that the University was unnecessarily harsh in handling the case. I am sorry that she had to go through the long and exhausting process to get the decision she did in the SCA ruling.

GM: Could you comment on the state of student activism at RU. Some students said they thought the pledges they signed when they registered at Rhodes prevented them from engaging in any protest activity at the university. This is clearly a misapprehension but seems to have had a ‘cooling effect’ on protest at RU. (a) What are your thoughts on this? (b) Do you think students are more empowered to engage in activism now than before the #RUReferenceList protests?

Macleod: Yes, as I remember it, there was a pledge that students had to sign stating something to the effect that they would not be involved in disruptive protests. I cannot remember the exact wording. I think that this has now changed. I suspect that whoever wrote the initial pledge realised that it would not stand up in court.

Protests have diminished, not just at Rhodes but at universities across the country. I think there are many reasons for this. First, the cohort of students who took part in the (more-or-less) three years of protests suffered significantly – including exclusions and jail. In a sense, the fight has gone out of them. Second, and relatedly, university managements showed that they were not afraid to take tough measures, including interdicts, calling police onto campus, and pursuing disciplinary measures against protestors. As Anthea Garman writes, there has been a real lack of listening and understanding. Third, COVID changed everything, including the possibility of disruptive protests.