By MANDISI MAJAVU, Senior Lecturer, Department of Political and International Studies, Rhodes University

One of the sources of social discontent in post-apartheid South Africa is the legacy of white racism. This toxic legacy is evident in racialised poverty and inequality.

It is a historical fact that the economic prosperity of whites in South Africa is based on the racist exploitation and impoverishment of blacks.

The long history of racism enabled white South Africans to enjoy one of the highest standards of living in the world by the 1970s. In his new book, titled Can We Unlearn Racism?, Jacob R Boersema, a New York University academic, shows that by the 21st century, white South Africans’ “lifetime work-related earnings on average are four times higher than for Africans”.

Add to this corruption, rampant crime, frightening levels of gender-based violence and failing political institutions: the outcome is a social horror show that produces misery for millions of black people. Former president Thabo Mbeki referred to this in his recent scathing critique of the governing African National Congress (ANC).

Mbeki also criticised the party for not being able to organise a racially diverse audience for the memorial service of the late ANC deputy secretary general Jessie Duarte. That, he said, showed that the ANC had failed to embody its fundamental value of non-racialism.

Mbeki’s thinking reveals deep confusion about “race”, racism, diversity and non-racialism. He falsely assumes that diversity means harmony.

Non-racialism is one of the unexamined dogmas of the ANC. It has its roots in the politics of Christian humanism that inspired the formation of the party in 1912. That humanism regarded Christianity as transcending race by offering “an ultimate goal of inter-racial harmony based on the brotherhood of man”.

Whatever solidarity there was between different racial groups in political structures like the Congress Alliance – which drew up the ANC’s “Freedom Charter” in 1955 – did not translate to the social world outside politics.

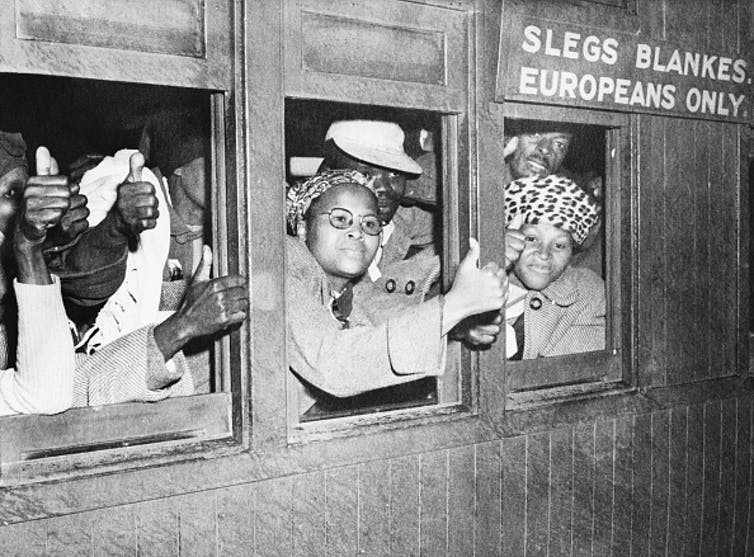

The world outside politics was defined by racial segregation. That has not changed much. Apart from the workplace and schools, ordinary blacks and whites continue to live racially segregated lives.

The ANC, since its formation, has been ideologically trapped in the 19th-century black Cape politics of Victorian liberalism – which advocated for loyalty to the British Crown. This resulted in blacks making moral appeals to white benevolence for justice and freedom instead of making political demands. The ANC has never fully understood how white racism functions.

The history

The ANC’s establishment in 1912 was driven by an ideological blending of British liberalism and a Christian vision of non-racialism. This equipped it poorly to respond to and make sense of racism and modern South Africa.

For most of the early 20th century, the ANC thought it could defeat racism by appealing to Britain’s sense of common justice. In his presidential address to the South African Native Congress (now ANC) in 1912 – which was published in the Christian Express, the Christian missionary journal published by the Lovedale Press – Reverend John Dube encouraged black people to show “deep and dutiful respect for the rulers whom God has placed over us” because the

sense of common justice and love of freedom so innate in the British character (would) ultimately triumph over all other baser tendencies to colour prejudice and class tyranny.

Consequently, from its formation to the 1950s, when its leaders were subjected to government bans, the ANC failed to win a single political victory over white racism, as historians have pointed out.

From the 1950s, it moved away from “black Victorianism” and incorporated a Pan-Africanist worldview, as well as Das Kapital – Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism. The Marxists in the ANC argued that the struggle aimed to overthrow capitalism, which they saw in terms of class rather than race.

Black people thus focused their hostility on the apartheid government and “never on whites as such”. Black people who dared to use race as an analytical category were eventually purged from the ANC.

By the turn of this century, the ANC had rid itself of British liberalism and Christian politics. But it remained committed to the idea of non-racialism. And it has embraced capitalism – particularly the capitalism entrenched in South Africa by white people.

There are three consequences.

Firstly, the ANC is an intellectually impoverished organisation that rewards incompetence and greed and encourages individuals to strive to be the king of the rubbish pile.

Secondly, corruption and blatant disregard for the law have achieved ambient levels.

Thirdly, South Africa is dysfunctional and social cohesion has broken down.

Failure of non-racialism

Mbeki is one of the few ANC politicians to admit publicly that non-racialism has failed to unite South Africans. The black intellectual ecosystem has yet to develop a compelling analysis of the relationship between white wealth and black poverty.

The white narrative that blames the black elite for the persistence of racialised inequality erases white racism from post-apartheid South Africa.

According to Statistics South Africa:

The labour market experiences of different population groups in South Africa continue to diverge substantially, and still reflect the strongly persistent legacies of apartheid policies … Thus, black African unemployment rates are between four and five times as high as they are amongst whites.

The black middle class remains largely an academic construct. It consists of a mere 4.2 million people, whereas blacks make up 80% of the population of 60 million. Research shows no sign of a decrease in racialised wealth inequality since apartheid.

The ANC’s failures mean that the vast majority of black people are trapped in poverty, with few prospects of escaping.

Thabo Mbeki is right to be worried. And it is not only the ANC that does not have the solution to the country’s problems.

Until black people break from the ideological capture of non-racialism, the legacy of white racism will never be dislodged.

This article first appeared in The Conversation Africa.