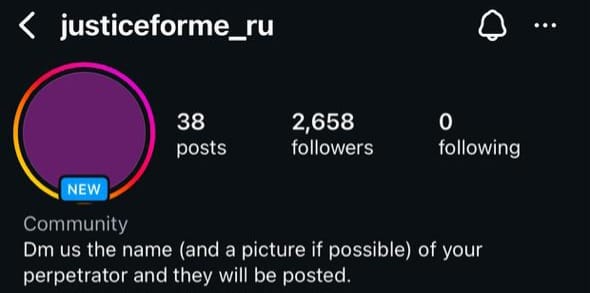

Social media has emerged as a new form of activism against gender-based violence, with TikTok, Facebook and Instagram becoming platforms where survivors are breaking their silence, sharing their stories, and publicly naming their abusers. This powerful movement to the online environment needs careful examination. Although social media offers survivors a voice when traditional systems have lost their trust, it also raises critical questions about justice, due process, and the potential for harm. An anonymous Instagram account, @justiceforme_ru, was created last Sunday, which prompted Grocott’s Mail to investigate this phenomenon.

The account, @justiceforme_ru, was created at approximately 8pm on Sunday night. By the next day, it had already published 58 submissions accusing people of rape, sexual assault, coercion, stalking and physical abuse. The account was deactivated on Monday morning, and a new one, @ru_referencelist, popped up. However, that account disappeared after two hours, and the @justiceforme_ru account was restored, retaining all its past submissions as well as new ones. By Monday 4pm, the account had gained more than 3 600 followers, and it was sitting on over 5 000 followers on Tuesday afternoon before it disappeared on Wednesday.

The story behind the account

The creator of the account, who refused to be named, said the page was born out of her own trauma. “I was raped by a senior lecturer. I can’t report him, he threatened me, and he’s made my life a living hell,” she told Grocott’s Mail. “I realised that if I can’t help myself, then I can help others. That’s why I started the page.

“Reading the stories makes you realise how much we are suffering. We can’t be aided because the people we run to don’t take our issues seriously.”

She said she was inspired by a former student, Simbongile Dlala, who recently shared her own assault online. However, the rapid traction the page gained left her overwhelmed.

When asked about potential legal consequences from those named as abusers she was defiant. “It’s not defamation when there is proof,” she said. “I’m doing the same thing that happened [with]the RU reference list, but it’s got more advanced now. I can’t predict what’s gonna happen, but I just know it won’t be without me fighting back.”

On the long-term future of the account, she was uncertain. “I intend to keep it long term, but I’m risking being excluded [from Rhodes University], so I really don’t know how that will play out.”

She says she wants Rhodes University in particular to start protecting victims and not perpetrators. “I’ve lost all hope in our institution; there’s not much they’ll do, obviously.”

She also believes that the South African Police Service is of little help: “The law will not take its course for very obvious reasons. The same cops that are meant to protect are also abusing and raping. So many people have confirmed that when they go to the police station, they are simply dismissed.”

The co-admininistrator question

Grocott’s Mail interviewed Simbongile Dlala, who initially refuted allegations that she was the admin of @justiceforme_ru but expressed complete solidarity with the account. However, recent Instagram story posts contradict this statement, showing screenshots that prove she was a co-admin.

When asked for clarity, Dlala said, “I was the co-admin, I did not create the account, I was added to it.” Dlala told Grocotts that she received threats once the posts started appearing, her address was doxed and her family members were threatened.

Dlala is also publicly accusing a fellow student of rape. “I filed a formal report to Rhodes [University], so my case with him begins next year since Rhodes is now on vac. I will also go through the court route,” she said. Dlala has also petitioned for his removal from Rhodes University on Change.org. By Thursday afternoon, the petition had 3 665 signatures.

The counter account

A counter account, @men_fightback_ru, was created on Monday afternoon. The anonymous administrator whose identity was later revealed on Facebook, told Grocott’s Mail the purpose was to allow men to “fight back” against what they believe is an unfair and incomplete public narrative.

“I post every reliable story. This page is contrary to the first one [justiceforme], where males are shamed without even clearly stating the scenario,” he said. “There are some women who have real cases. Also, there are some who are trying to sabotage others because they dislike them.”

He described Rhodes as “toxic for men” and said he was “convinced that only men with proof can fight back and tell the real story.”

The Rhodes response

The Director in the Office of the Vice Chancellor continues to work tirelessly to defend and support the victims of GBV, said Caroline Rowland, Rhodes University Interim Director of Communications. Students found guilty of rape are permanently excluded from the university and their academic transcripts are endorsed as ‘conduct unsatisfactory’ she said.

It is, however, impossible for Rhodes to take a matter forward if an allegation of GBV is not formally reported to the university through the well-established and widely-publicised processes. “Given that South Africa is a Constitutional Democracy, the kind of social media activity we have witnessed in recent days, may unfortunately result in criminal proceedings against the accuser, far outside the jurisdiction of the university”.

The legal minefield

All these social media accounts and public outings have left Grocott’s Mail with many questions about the legal implications of social media as a platform to seek justice. We consulted two experts to understand the implications of doing this.

Taryn de Vega, a media law and ethics lecturer at Rhodes University, was blunt about the risks. “If somebody names another person on social media with the aim of hurting their reputation in the eyes of society, it’s seen as a gross overreach of freedom of expression,” she said. “The burden of proof to verify the claim, if it is defamation of character, will rest on the person making the claim.”

We also had a conversation with social media legal expert Rorke Wilson, who explained that simply labelling posts as “alleged” offers no legal protection. “The administrator of the page is as responsible as the people who make the submissions,” he said. “They are equally responsible in the eyes of the law because of the editorial power that they hold.”

The risks are threefold: criminal injury to dignity charges, protection orders that could lead to arrest, and civil defamation claims. Even those who submit stories anonymously aren’t safe — administrators can be compelled to reveal their identities.

However, Wilson said survivors do have a defence as they have a right to share their stories, if they can prove their claims are true and in the public interest, and in the light of gender based violence being a national disaster, they have a strong argument. “If you have evidence that will hold up in court, then you will benefit from the defence of truth and public interest.” But therein lies the problem: sexual assault rarely leaves the kind of evidence that satisfies a courtroom.

Those who share or amplify the posts face risks too. Wilson pointed to a UK case where Lord McAlpine sued approximately a thousand people for defamation after they repeated claims about sexual misconduct investigations. “I don’t want people to assume that just because everyone’s posting, they’re immune,” Wilson said.

‘Symptom of the failures of the justice system’

Both experts acknowledged the failures that drive survivors to social media in the first place. De Vega cited statistics showing that roughly 70 percent of South African women don’t report rape or abuse to police. “Our policing system is brutal in how women are treated,” she said. “Victims are pulled through a court of public opinion almost, and they have to relive the story. It’s challenging. Our legal system is slow.”

She noted that movements like #MeToo and #AmINext allowed victims of violence and sexual coercion to tell their stories online. “For a lot of women, finding solace in online communities where they can share their story has become a regular occurrence.”

Wilson was equally critical of formal systems. “I’m not at all surprised at people’s lack of faith in the justice system,” he said. “We very rarely will even advise our clients to go to the police unless we know they’ve got sound evidence, because the police are very unwilling to help. There’s a lot of victim blaming that can go on.”

He sees social media callouts as “a symptom of the failing of our justice system, something we want to fix, because things do go better when we follow the right processes”.

The danger, he said, is that when allegations go viral without verification, the impact of getting it wrong is massive. “People have agency over their own story, but that shouldn’t be the solution we’re gunning for, because then we just open our victims up to more chances to be further traumatised.”

De Vega described the new reality: “Social media has changed this environment rapidly. People are sharing their stories and because everyone is a journalist, everyone is a storyteller, the old rules of who is allowed to tell the story and when and within the confines of the law really no longer exist.”