By Chalotte Mokonyane

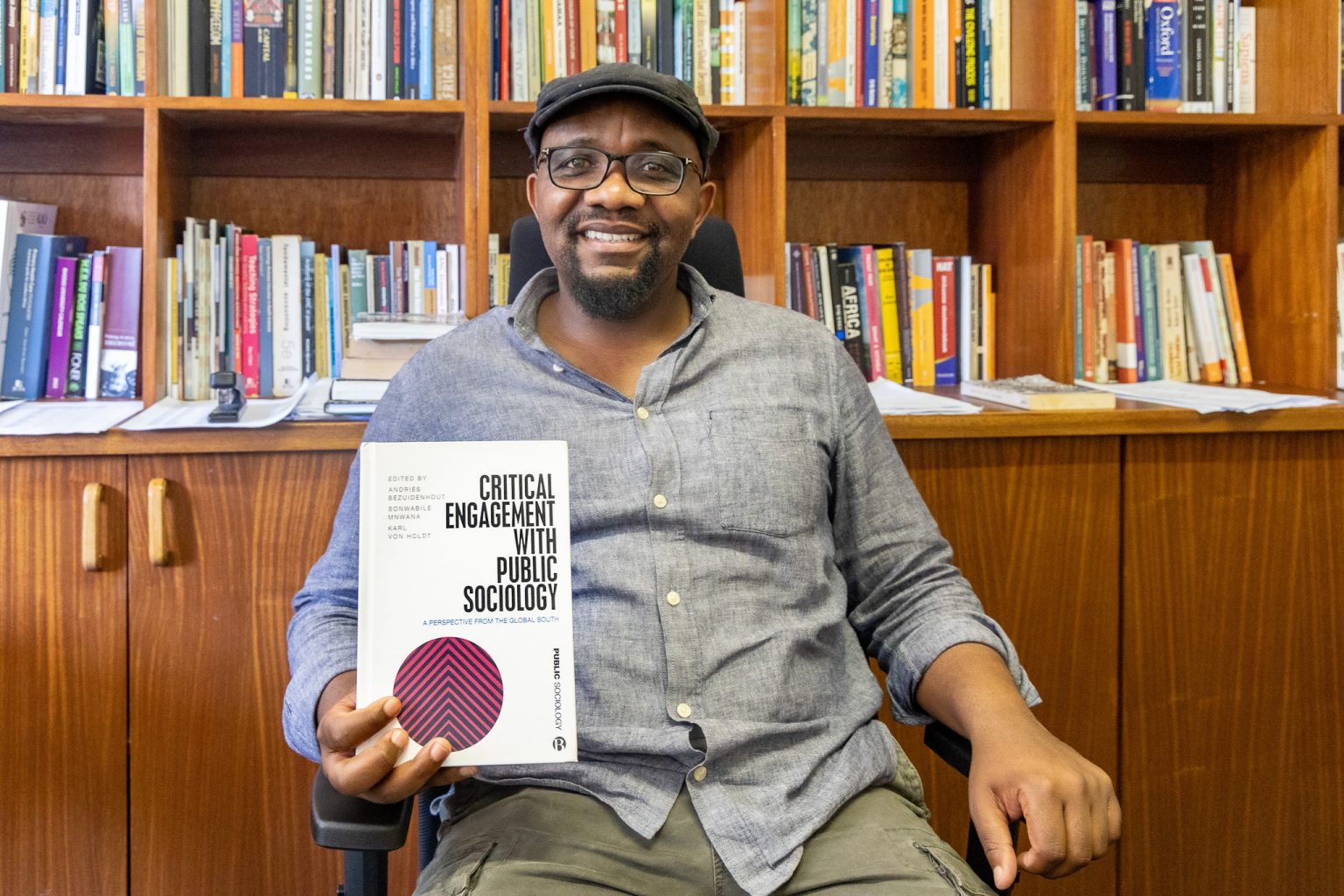

Professor Sonwabile Mnwana, a leading scholar from the Department of Sociology and Industrial Sociology, has recently been awarded a prestigious Tier 1 SARChI Chair in Sustainable Rural Futures. This significant appointment marks a renewed focus on tackling the deep-seated, complex challenges faced by South Africa’s rural areas, particularly in the Eastern Cape.

The legacy of the homelands

Mnwana’s motivation is rooted in his desire to contribute to the Eastern Cape, a province that inherited the former apartheid homelands of Transkei and Ciskei. These areas, he explains, were designed not for production but as residential spaces for vast numbers of Black people, primarily serving as reservoirs of massive cheap labour that oscillated between the rural areas and industrial centres. This pattern tragically persists today, he noted.

The rural areas, especially where Black people reside, are characterised by a confluence of crises:

- deep poverty and inequality

- weak and contested institutions

- ecological vulnerability, where the poor are disproportionately exposed to climate crises like floods

- unjust energy arrangements

- rapid decline in farming leading to massive food shortages and malnutrition

- poor education standards and high unemployment among the rural youth

The goal of the chair: beyond the land question

The core goal of the chair is to grapple at a fundamental level with these challenges. Mnwana stresses the importance of considering the gender dimensions, as women who are often responsible for social and production tasks, are the most severely affected. The central research question guiding his work is: “What resources social, intellectual, cultural, ecological, political, and economical can the poor in southern Africa utilise and access to envision and achieve sustainable futures in the rural spaces where they live?”

While the land question is vital and has historically dominated policy interventions, Mnwana aims to go beyond it. Policies have often focused on how to use rural land to improve livelihoods, create jobs, and end poverty. His approach is to create a space for the rural poor themselves to be part of the reimagining of their own futures, ensuring that the knowledge generated influences policy directions to enable this.

Sustainability and the mining dilemma

Mnwana defines sustainability in the traditional sense: utilising current resources without jeopardising future generations’ opportunities. This concept is sharply contrasted with the challenges posed by mining, which while potentially lucrative, is transitory and extremely devastating to the environment and can cause serious social ills. He highlights that in communal areas like the former homelands where millions of families have lived for centuries mining displaces huge populations, unlike in areas of private land ownership. Since no sustainable solutions have been put in place for these displaced families, the relationship between mines and rural communities in South Africa remains profoundly antagonistic. The lack of long-term economic, social, and environmental sustainability often leads communities to reject mining proposals.

The role of traditional leadership and land rights

A significant part of his work explores the contentious issue of customary land rights and the role of traditional leaders. Mnwana points out the misconception that rural communities are homogeneous ethnic groups whose interests are exclusively represented by traditional leaders.

Customary law, he argues, does not give traditional leaders exclusive power over land. Decisions over allocated land rest with the family unit, and traditional leaders do not have the power to alienate land or allow resource exploitation by outside interests without the consent of the landholders. The frequent non-congenial relationship between mining companies and communities stems from investors and the state bypassing communities and only consulting with traditional leaders, which is a distortion of customary practice.

He highlights the importance of the Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act (IPILRA), a critical but often overlooked piece of legislation. This law protects the informal land rights predominant in rural areas, allowing customary land holders to invoke it and demand consultation, partnership, and clarity on benefits before any major project, such as mining, can proceed on their land.

Public sociology and practical impact

Mnwana is committed to public sociology and ensuring that his research directly benefits the communities studied. This will be achieved through co-production of knowledge, where communities are not just subjects but active partners in designing and executing the research.

The research won’t just generate academic publications; it will seek a notable impact by:

- Engaging a diverse group of social actors, including policymakers, development agencies, and the private sector.

- Developing practical recommendations for the production of commodities like wool, mohair, and medical cannabis to help local farmers commercialise their products.

- Formulating policy briefs and hosting community forums and workshops where research findings are presented to all.

The overarching goal is to resuscitate and revitalise farming and other land-based livelihoods, making them attractive to the rural youth, and influencing policy to address infrastructural deficits (water, medical care, schooling) that drive the rural-to-urban drift.