By Brianna Msiza

Storytellers, librarians, authors, and illustrators from across South Africa converged on Makhanda this month, united by a shared mission: to strengthen children’s literature in a country where young readers desperately need books that reflect their lives and languages.

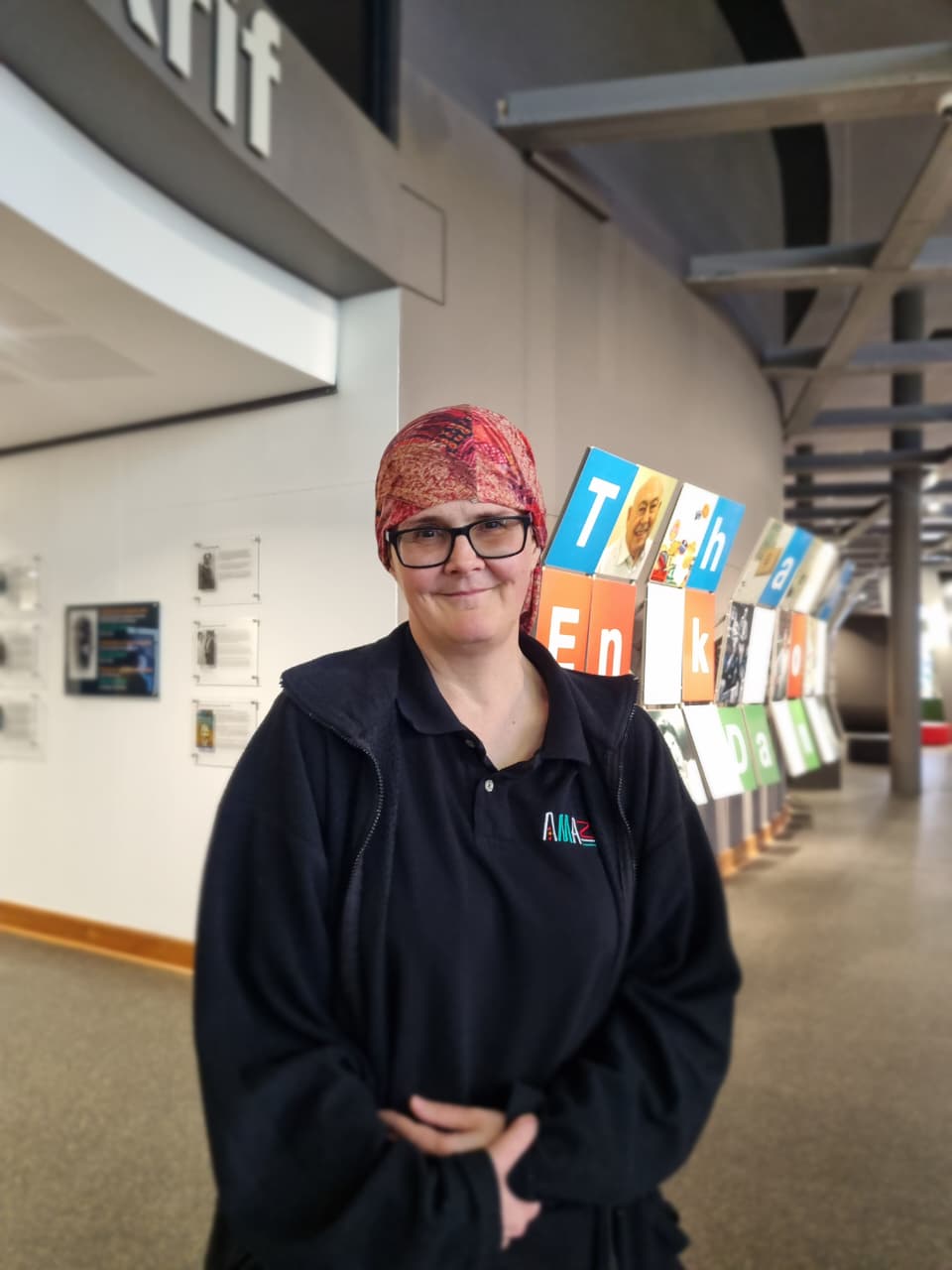

The Amazwi South African Museum of Literature held its annual Children’s Literature Conference last weekend, featuring presentations by diverse voices in the children’s book industry. But as Crystal Warren, manager of the Curatorial Division at Amazwi, explained, the gathering was about much more than academic papers.

“At one stage, there were several universities that were hosting conferences on children’s literature; University of Northwest, then Potchefstroom, Unisa had some, but that had fallen away. I think the people organising had retired and their interests had moved,” said Warren. “A few years ago, we decided that there was a need for such a thing, that so many people are doing really good work in children’s literature, but often in different areas. Things are happening with librarians, with teachers, with literary scholars, and with literacy associations. So, we wanted to bring these diverse groups together so that we can learn from each other, we can share research, especially since in the academic world, often children’s literature is marginalised.”

A call for diverse voices

Speakers for the conference represented a wide cross-section of the children’s publishing sector. Marike Beyers, a literary curator at Amazwi, described the selection process: “We send out a call. So, we send emails to different departments and to people who have attended before. And we put it on our Facebook page and various literary pages. And then we ask people to submit a call for papers, if you are interested, writers submit a short abstract, a short idea about what you want to present by this date. And then we make a selection from there.”

The conference featured prominent figures including Madoda Ndlakuse, Amanda Sickle, and Nolwakhe Yvonne Sewelo, among many others in the industry.

Ndlakuse, a storyteller, speaker, poet, writer, and literary activist, delivered the keynote address. In it, he proposed that actively supporting the publication of books written by children, books which reflect socio-cultural experiences and references that children can relate to, is a means to elevate and reinvigorate indigenous African perspectives as community resources in increasingly fractured socio-cultural and politico-economic settings.

“I believe that the Amazwi Children’s Literature Conference is relevant, and it is needed. It is necessary for the literacy ecosystem in South Africa,” Ndlakuse said. “When I’m listening to each speaker and the people responding from the floor, I love the subjects that we get to learn about. Some of them are very sensitive, but they are helping. This is also linking to Nal’ibali, because it is a national reading-for-enjoyment campaign with the main aim of sparking children’s potential using things like the Nal’ibali newspaper supplements used in reading clubs. We are very big in storytelling.”

Books in the hands of children

Another standout presenter was children’s author Amanda Sickle, who brought more than just ideas to Makhanda. “I’m from the Reading Room, which is a literacy organisation I founded in 2012. I’m a distributor for Book Dash. This year I was allocated 18 000 books which I distribute to Early Childhood Development centres in Mitchell’s Plain and the Cape Flats,” said Sickle. “As soon as I had some left, I thought, let me bring them up to the children here in Makhanda. They are now with the museum to use at their discretion with the education project and give to the kids in the schools.”

Sickle explained that she submitted an extract after seeing a call for papers, and that’s how she ended up at the conference.

Storytelling beyond the page

The conference also featured a children’s programme led by ‘Minister Yveslight’ Nolwakhe Yvonne Sewelo, who is heavily involved with children’s literature and was one of the speakers on the first day. Her presentation, titled “Embodied and cultural learning: A phenomenological exploration of using Xhosa syllables in music education and movement-based chess instruction,” presented a different mode of storytelling.

“I’m an author and I’ve authored six books. A lot of people tend to only look at the area of reading, but I’m more focused on the way of telling stories. I’m trying to bring in different ways of storytelling,” she said.

Isidlalo, from Mount Frere, is one of the different ways of telling stories that she wants to introduce, as well as canon singing, which involves body percussion, singing, and dancing. This way of storytelling has deep ties with her musical background, which she obtained while pursuing her studies both locally and internationally in music.

When asked about the conference, Sewelo said it introduces children to storytelling in all its facets. “In doing so, you will then encourage the children not to read for the purpose of passing or scoring points or getting a certain percentage in the classroom, but read for enjoyment, read for understanding, read to get the perspective of other people.”

Building connections, building community

Warren emphasised that while the academic papers are important, the real value lies in the connections made between sessions. “It’s as much about the papers, which are important, but also about the connections and the conversations over teas and lunches,” she said. “It’s just helping to make connections and find ways to work together and for people to be able to share the work that they are doing. It also just helps to prioritise books for children and how important they are for reading, for pleasure, for literacy development, for emotional development of young people, and the importance of getting books written that are appropriate.”

People talking about folk tales, young adult fiction, and retelling classical texts using contemporary themes came together to share their ideas and build connections that will hopefully strengthen children’s literature in South Africa.