By Nosiphiwe Nyangana and Rod Amner

Only one in four Grade 4 learners in Makhanda can read for meaning in isiXhosa, according to the 2025 Reading Comprehension Study by GADRA Education and the Rhodes University Education Department.

This sounds dismal. But compared with the international PIRLS tests in 2021, where just 13% of children taking the test in an African language passed the reading for meaning benchmark, Makhanda’s 25% is relatively high.

The 25% figure comes after years of support from Funda Wande, a literacy and numeracy programme that has brought structured materials, coaching, and teacher training to some local isiXhosa language primary schools. While teachers involved praise the resources and report feeling more confident, the still-low local test results reveal the significant challenges ahead.

Founded in 2017 by Nic Spaull with support from the Allan Gray Orbis Foundation Endowment, Funda Wande aims to ensure that every learner can read with understanding by Grade 4. But unlike many education NGOs, Funda Wande adopted what researchers call a “learning by doing” strategy by piloting, adapting, and building partnerships with the government rather than working around it.

Teachers of African language foundation phase classes lack opportunities to get specialised knowledge in teaching learners to read, and their classrooms have insufficient African language reading materials. In Makhanda, Funde Wande trains teachers, provides classroom materials in isiXhosa and maths, and offers continuous coaching to improve early literacy and numeracy outcomes.

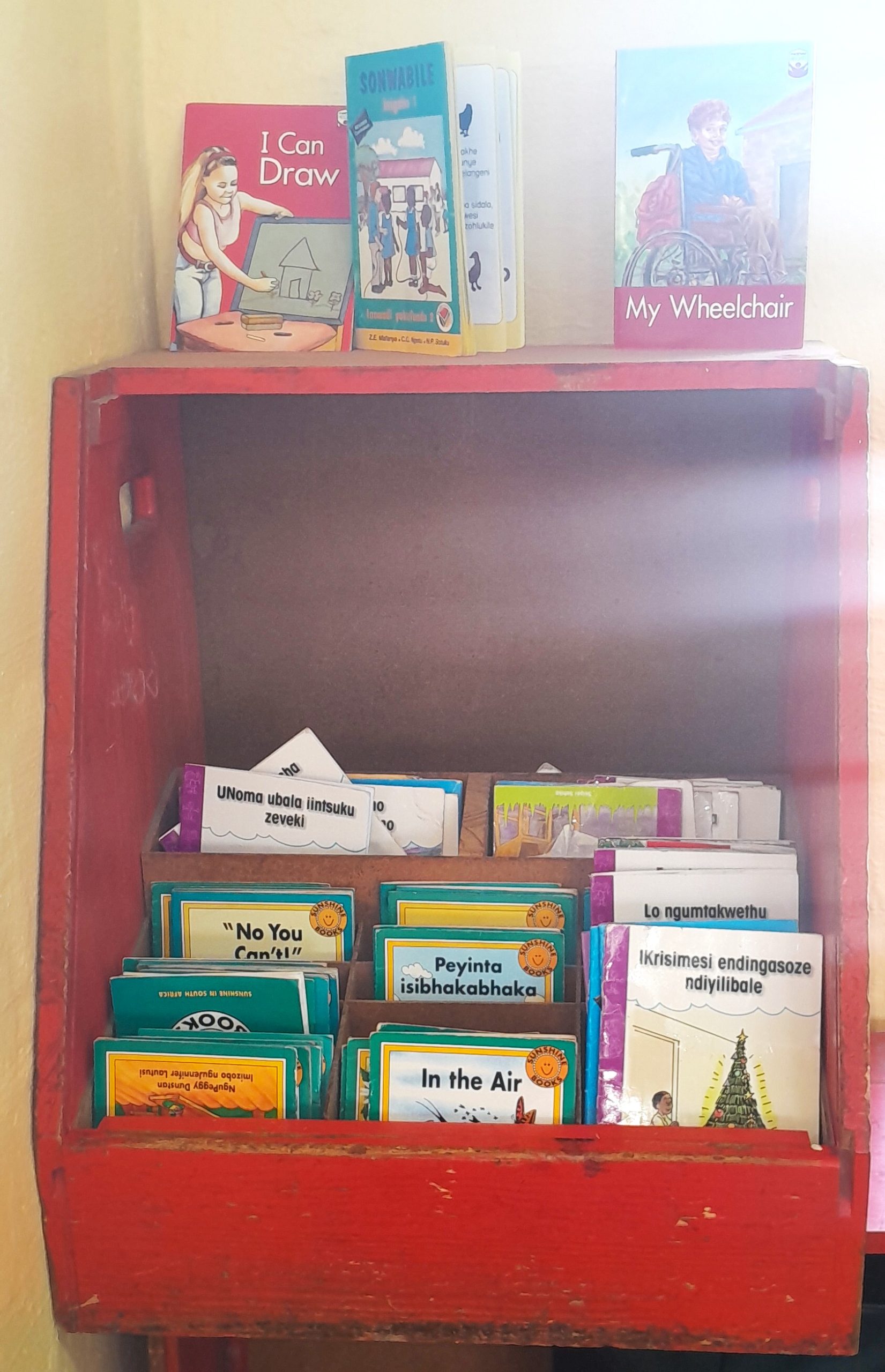

Through its partnership with the Eastern Cape Department of Education, the organisation has worked with three local schools: Samuel Ntlebi, Fikizolo Primary and Archie Mbolekwa. Each of the selected teachers receives isiXhosa lesson plans, VulaBula readers and posters that are aligned with the CAPS curriculum. Coaches visit classrooms regularly, model lessons, provide feedback, and train one teacher to serve as a coach when they leave.

Funda Wande coaches like Nomalungelo Zono visit classrooms regularly, model lessons, provide feedback, and train one teacher to serve as a coach when they leave. The department helps identify schools, releases teachers for workshops, and monitors progress to ensure the work remains sustainable.

The view from the classroom

Zono, who is based in Makhanda and works with schools in the Sarah Baartman District, explains, “We go into classrooms, observe lessons, and work hand-in-hand with teachers; it’s not just theory, we show them how to teach guided reading, phonics, and comprehension. The goal is for every learner to read with understanding by Grade 4.”

At Samuel Ntlebi Primary, Grade 1 teacher Bukiwe Wakashe says Funda Wande helped her gain confidence in her teaching. “The lesson plans and posters make things easier for us,” she says. Her learners can recognise sounds, read simple isiXhosa stories, and even enjoy reading isiXhosa. They can count confidently on the materials from Bala Wande.

Fridays are often used for spelling and revision, which has led to her learners winning the isiXhosa spelling bee competition for the last two years. “If Funda Wande were there from the beginning, there wouldn’t be a child doing maths lit,” said Wakashe.

Nozuko Kepe at Fikizolo Primary School says, “If Funda Wande were to return with their material, we would appreciate their books being enough for every learner; it would be really effective.” Her comment points to one of the programme’s practical challenges: materials don’t always reach every child, and when coaches leave, the resources go with them.

The implementation challenge

Even with teacher buy-in and quality materials, translating good design into classroom practice has proven difficult. A 2021 qualitative study of Funda Wande implementation found that “implementation fidelity to the programme was overall low, with teachers not following the programme as a structured and sequenced daily programme of learning”.

Instead, teachers treated the materials as resources to draw from selectively rather than as a complete instructional system. The study found that teachers often simplified activities, skipped components, and maintained longstanding teaching habits that limited effectiveness like collective rather than individual reading and writing, as well as minimal feedback to individual learners, slow pacing, and low expectations.

“The program still contained a number of moving parts, and material was not used in a way that capitalised on its aligned design,” the researchers noted. Late delivery of materials and COVID-19 disruptions likely contributed to poor uptake.

Even so, the study found that classrooms receiving Funda Wande support scored higher than other classrooms on measures of instructional quality. “Funda Wande classrooms offered a greater range of reading activities and spent more time on reading,” and “the insertion and use of more and better text appears to affect learners”.

Government partnership as a strategy

Funda Wande understood early that its impact would depend on influencing how the government spent its education budget, not trying to work around the system. The government spends 99 times more on education annually than all philanthropies combined.

The organisation continuously engages officials at the district, provincial, and national levels. When the Eastern Cape’s top leadership changed suddenly and the new director wanted to cancel the pilot, Funda Wande scrambled to rebuild the relationship.

The stubborn gap

Yet with three-quarters of Makhanda’s Grade 4 learners still unable to read for meaning, the question remains: why isn’t good design plus teacher support plus government partnership adding up to transformed outcomes?

The 2021 study identified six “dominant teacher behaviours” that act as blockages, including treating reading and writing as communal rather than individual activities, holding low expectations, providing little individualised feedback, and managing time poorly. The researchers noted that these patterns “have remained resistant to change” even with program support.

However, Zono is upbeat and believes Funda Wande’s impact goes beyond just literacy results. “When learners read with understanding in isiXhosa, it builds confidence,” she says. “It helps them in every subject. Reading is the foundation of everything.”

For schools like Samuel Ntlebi and Fikizolo, Funda Wande has brought tangible value: better materials, clearer lesson plans, and support. However, whether these inputs can be used effectively enough to move isiXhosa reading outcomes beyond 25% remains to be seen.

South Africa’s literacy crisis is rooted in teacher training gaps, poverty, infrastructure constraints, large class sizes and pedagogical habits formed over decades. Shifting those realities requires not just good programs, but sustained pressure on multiple fronts simultaneously.

Funda Wande has delivered quality materials, trained coaches, government partnerships, and local capacity. But it has supported a sprinkling of teachers in a handful of schools in the city. A system-level transformation is required.