By Thandiwe Johnson

My childhood wasn’t of toys and games but of the rich aroma of ink and aged paper, and my lullabies were the melodic echoes of diverse languages, whispering from the corners of the street. I grew up with a tapestry of different languages in my neighbourhood, what I would call “the centre of Africa”, a place where the aroma of Umgqombothi (Sorghum beer) from eMcimbini (traditional ceremony) mingled with a sweet scent of Koeksisters from the Afrikaner kitchen. On this street, the laughter of the children of AmaXhosa, Mapedi, AmaZulu, and MaTshwana echoed. At the same time, a hot pot of potjiekoes bubbled alongside the comforting aroma of morogo and chibuku. In this place, tongues danced between IsiXhosa, SeSotho, SeTshwana, IsiZulu, and Sepedi, choreographing a rhythm that I would forever dance to. But at the very heart of the ‘Centre of Africa’ lies the cherished spirit of my grandmother, uMaNqosini, uGaba, uThithiba, uCihoshe, uMamlambo; despite being uneducated, she had a wealth of stories not from books but from her life.

………………………….

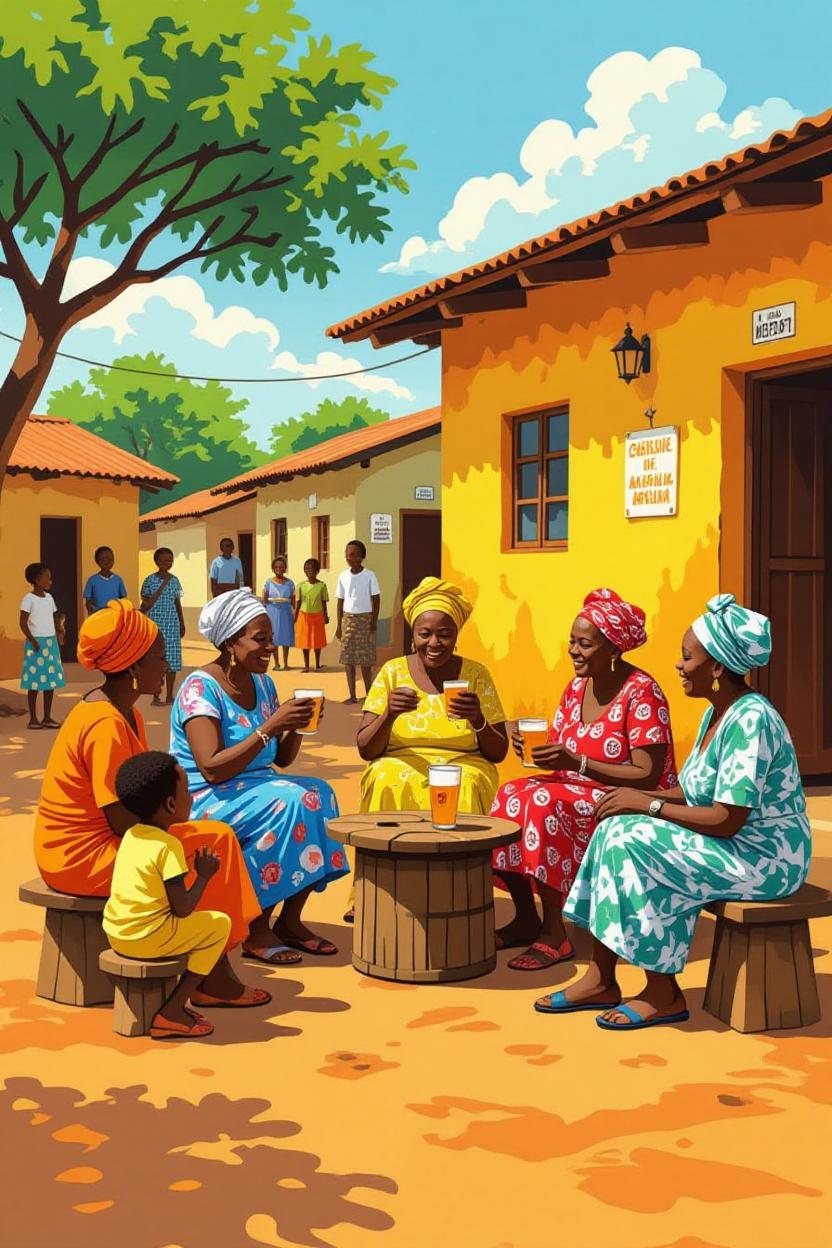

It’s a sunny afternoon, and my grandmother is hanging out with her friends at the shebeen, sipping their R8 chibuku. My inner thief unleashed, I sneak out from under their table and spot their chibuku, grab it and run. After my daring heist, I take a big, delicious sip – that thing hits harder than milk, and suddenly, I am swaying like a little penguin.

Meanwhile, my grandmother and her friends are wondering where their precious chibuku has disappeared. Finally, I wobble back into their view, and they laugh. Here I am, a little party animal with a sagging diaper.

As we walk back home, I hear their conversations in different African languages.

My mother sees our group walking back. Then she sees me and bursts into tears, not tears of anger but disbelief.

“Ma kutheni umntana enje?” (Ma, why is the child like this?)

“Hayi naku umntana wakho Ube ichibuku yethu wayisela” (Your child here stole our chibuku and drank it.)

“Nombulelo Nako engwe Naya ngwana wa gago R8 gore a ithekele chibuku ya gage, gore a tlogele go utswa ya rona” (Next time, give your child R8 to buy herself a chibuku, so that she stops stealing ours.)

“Ons is moeg van jou kind ons chibuku steel, dis is nie die eerste keur nie” (We are tired of your child stealing our chibuku; this is not the first time.)

This is Ous Tshidi and Ous Sanna, two grandmothers living in my neighbourhood who also raised me and influenced my love for Afrikaans and Setswana.

“Geen manier dat ek my kind R8 Vir chibuku gee nie.” (No way I’m giving my child R8 for a chibuku), Le dira ngwanaka letagwa. (You guys are making my child a drunkard.) Ma iya ekhaya uyolala tuu. (Ma, go home and sleep tuu.)

“Andiyolala mna, ndoziqibezela la chibuku yam” (I’m not going to sleep; I will finish my leftover chibuku).

She grabs her steel chair and puts it beside the door with her leftover chibuku. As the evening breeze sweeps through, she begins to sing what we call Amagwijo. Her voice, filled with pain, regret, and anger, echoes through the neighbourhood, carrying those emotions with it. I nestle myself right between her legs, my head against her knees, captured by her voice. After a long pause, she stops singing and tells me stories about her life.

“Yazi Hoho ubomi bam bonke, ndancama amaphupha am ndakhulisa abantwana basekhaya. Ukubabukela xa besiya esikolweni yayiyinto ekrakra endingasokuze ndiyilibale. Ndandirhalela ukuba sezihlangwini zabo, ndifunde iincwadi de kutshone ilanga. Ndandinqwenela ukuba ngumfundisi-ntsapho nombhali, ndibhala amabali ngesiXhosa abhiyozela inkcubeko nezithethe zethu. Nangona ndingazange ndilifumane ithuba lokuqhubeka nemfundo yam njengoko ndandinqwenela, kodwa ndibona into ekhethekileyo kuwe. Ndifuna ukuba wamkele uvuyo lokufunda zonke iincwadi onokuzifunda kwaye uzibhale ngokukhululekileyo, ngaphandle kokuzisola okanye imithwalo” (My entire life, I sacrificed my dreams to raise my siblings. Watching them go to school was a bittersweet experience I will never forget. I longed to be in their shoes, reading books until sunset. I aspired to become a teacher and an author, writing stories in IsiXhosa that celebrate our culture and traditions.

Although I never had the opportunity to pursue my education as I wished, I see something special in you. I want you to embrace the joy of reading all the books you can and to write freely, without regrets or burdens.

I cannot find the right words to ease her pain or wipe her tears; I am just five years old.

…………………………

At the age of 10, with my grandmother by my side, I started devouring books in different languages, not just focusing on the plot but immersing myself in each unique culture, walking door to door in my neighbourhood, collecting all the books, asking questions, translating and experiencing each tradition.

Then the unthinkable happened…

My grandmother’s stomach cancer devoured her intestines, and she passed away. There was silence, the house felt empty, the chibuku became bitter, and the books collected dust. The grief almost extinguished my love for reading. Still, I remembered my grandmother’s words: “Ndibona into ekhethekileyo kuwe, ndifuna wamkele uvuyo lokufunda iincwadi onokuzifunda kwaye uzibhale ngokukhethekileyo ngaphandle kokuzisola okanye imithwalo” (I see something special in you, I want you to embrace the joy of reading all the books you can and to write freely, without regrets or burdens).

I found myself again immersed in books, not just from the school curriculum but from the corners of my street, seeking out more stories in different languages, wanting authors who resonated with the blend of cultures I had grown up with. Every book became a tribute to my grandmother; it opened new doors for me to express the experiences of my community and my personal journey. It taught me to not only embrace the diversity of African cultures but also to respect and celebrate the differences between each language.

Now, at 22, I realise that my love for reading and writing in different languages is rooted in my grandmother’s memory. She ignited the fire within me to keep African stories alive. It’s no longer just about consuming stories; it’s about creating them. I am committed to writing, not only for myself but for my community, so that their stories—our stories—remain alive.

The whispers of many tongues from my community continue playing, and I am forever grateful to be part of it.