By Rosemary Smith, Jennifer Bowler, and Helen Holleman, Quakers/The Religious Society of Friends, Eastern Cape

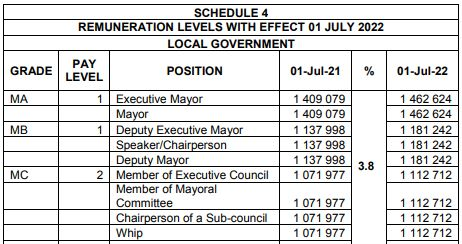

The proposed salary scales which appeared in a Government Gazette last year struck a chord, given the levels of poverty in our small city of Makhanda. If we take the amounts on face value at about R1.2 million a year, we then deduct tax of R368 867, we are left with an income of roughly R70 000 per month.

If we then use the income comparison indicator at the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) website and we assume a family of five, this equates to an individual income for each member of the household of R14 000.00 per month. This puts these individuals in the top 3% of income earners in the country.

About 97% of individuals in SA have a smaller – much smaller – monthly income. This makes tragic sense: we are one of the most unequal countries on the planet, and these figures show it – as do the huge differences between chief executive officers (CEOs) in the private sector and their lowest-paid workers. Way back in 2010, then Minister of Economic Development, Ebrahim Patel proposed capping the salaries of all who earned more than R550 000 per year. He was shouted down.

From a Quaker perspective, we find this imbalance disturbing because it flies in the face of the values we hold dear:

- Firstly, we favour a more equal society. Equality is about seeing that of God in everyone so all people are equal. But it also means that we favour greater equality of income. While we accept that absolute equality is unrealistic, we do believe that we must strive for greater income equality. This means raising the level of the lowest paid and putting a constraint or cap on higher-income earners. As Quakers, we have already publicly proclaimed our support of the UBI (universal basic income) grant to raise the income of the poorer members of our society, and equally, we intend to champion wage constraint for high earners in both the public and private sector. We know how damaging high-income inequality can be – it is well documented around the world, and we see evidence of it in our society in every headline that deals with violence, corruption, crime, mental health issues, and teenage pregnancy – all issues that are found to be worse the higher the income inequality.

- Secondly, as Quakers we value integrity – with this comes the sense that if we are paid for a task, we need to provide value for that payment. Can officials and councillors within Makhanda truly claim that they are delivering the services to the town for which they are being paid? The consequences of non-delivery are evident in the deepening poverty and distress of the citizens; in the failing infrastructure, in the lack of supervision of work and workers, in the breakdown of the social contract between the owners of the town (its citizens) and the people employed to care for them (the Municipality and Council).

- Thirdly, as Quakers we value sustainability. Sustainability applies to all our systems, the economic system, the political system, and the environmental system. The financial system in the municipal sector cannot sustain the salaries being paid to officials – municipalities around the country are in a state of financial collapse, which further exacerbates the inequality and poverty of the citizens.

- Fourthly, as Quakers we value simplicity: can we live within our means? Do we need expensive cars, expense accounts, flashy clothing, etc?

- Fifthly, as Quakers we value community, the collective, the understanding that I should do unto others as I would have them do unto me, or the notion of ubuntu which embraces the responsibility we each have to the collective and the collective good. To excessively reward myself at the expense of others goes against the moral principles laid down by African spirituality and all other major religious traditions.

- And finally, as Quakers, we strive for a peaceful world – and there can be no peace where there is injustice. There can be no peace where a few are rich, and many are poor; where the few extract from the community and so ensure a lack of development and sustainability. Peace is brought through working towards greater equality and ensuring the welfare of the collective.

If nothing else, municipal officials should see that there is a strong moral case for income constraint, as well as a strong self-interest imperative for income constraint.