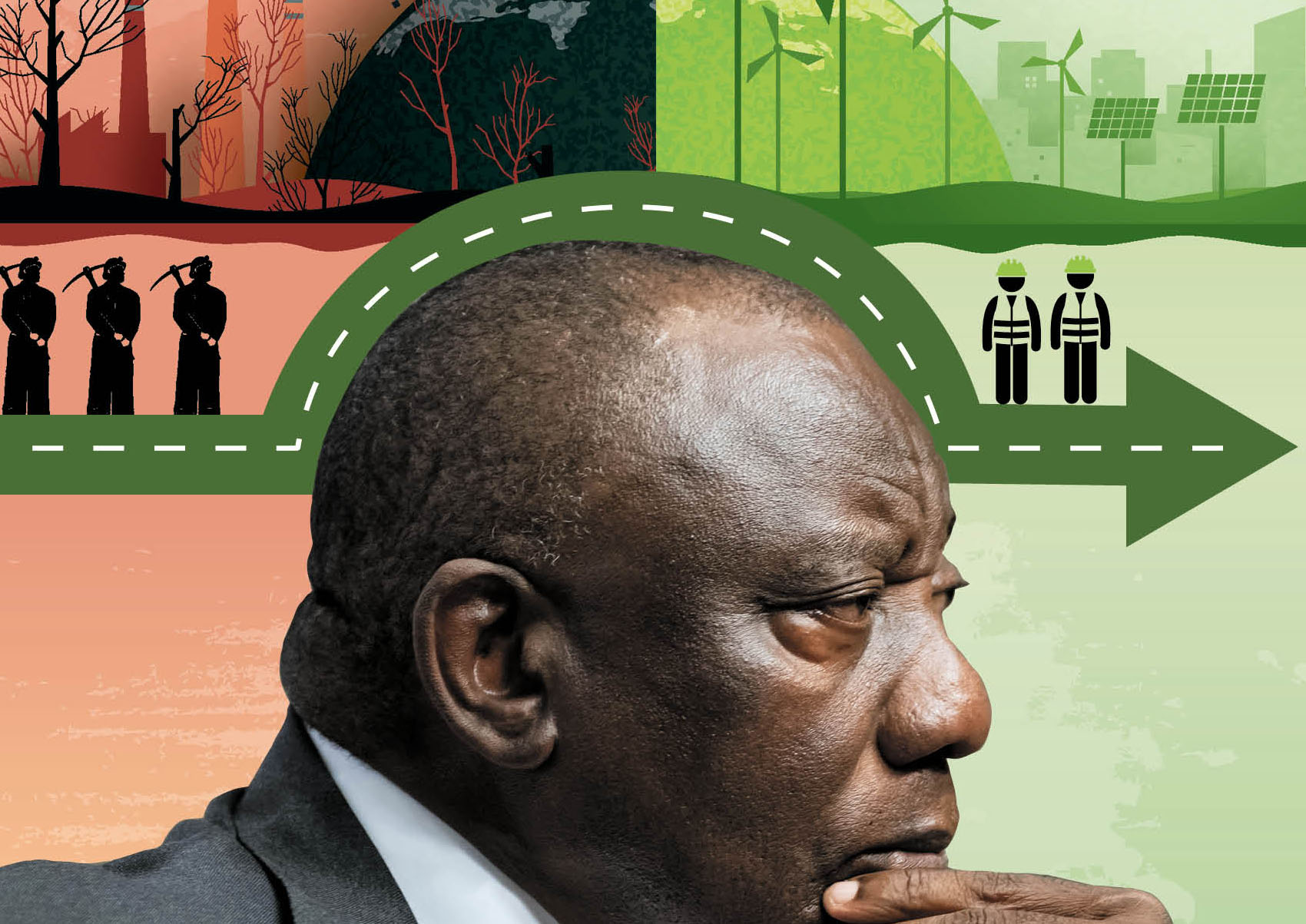

Global leaders have praised President Cyril Ramaphosa for South Africa’s efforts to prevent and avert the worst effects of human-induced climate change as part of its Just Energy Transition Investment Plan, write ETHAN VAN DIEMEN and SHARM EL-SHEIKH for The Daily Maverick’s Burning Planet.

After speaking at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27), which is taking place from November 6 to 18 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, President Cyril Ramaphosa has been praised by world leaders for South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP), which is designed to accelerate the move away from coal in a way that protects vulnerable workers and communities, and develop new economic opportunities such as green hydrogen and electric vehicles.

It is part of South Africa’s efforts to prevent and avert the worst effects of human-induced climate change – from heat waves, floods and cyclones to multiyear droughts and sea level rise.

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, US President Joe Biden, French President Emmanuel Macron, and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz have all commended South Africa for its commitment to clean energy but, significantly, the country’s emphasis on assisting workers and communities who will be affected by job losses as we become less reliant on the coal industry.

Earthlife Africa Director Makoma Lekalakala sums up why South Africa’s JET-IP is a game-changer for all South Africans who have been hammered by load shedding.

“We need clean, cheap renewable energy to end the load shedding caused by our failing coal fleet and to address the energy poverty hampering social justice and development for all.”

Lekalakala also welcomed the recent release of the five-year, R1.5-trillion investment plan that details how South Africa plans to transition and transform the South African economy, which has for decades been powered by fossil fuels – particularly coal.

South Africa is among the top 20 highest emitters of planet-warming greenhouse gases. It accounts for nearly a third of Africa’s emissions, mainly due to Eskom’s legacy dependence on coal for electricity generation.

From moving people and goods around to how we light up our streets and homes, the plan seeks to clean up South Africa’s act without leaving anyone behind.

Mandy Rambharos, former general manager of the Just Energy Transition office at Eskom, said several banks, including the World Bank and the African Development Bank, said South Africa’s plan is the best they had seen on the table out of 14 plans from around the world.

“While I was at Eskom, we were approached by the Vietnamese, the Indonesians, the Philippines and the Indians to say, ‘we’ve looked at your plan, we’ve looked at what you’ve done, how did you do it, show us how you did it’… and wanting to collaborate with us.”

One of the reasons that South Africa is recognised as a leader in its moves towards a just energy transition is because of the multistakeholder consultative process that saw the drafting of a Just Transition Framework.

The Presidential Climate Commission (PCC) in July this year released the framework that sets out a shared vision for the just transition, principles to guide the transition, and policies and governance arrangements to give effect to the transition from an economy that is predominantly reliant on fossil fuel-based energy, towards a low-emissions and climate-resilient economy.

Dr Crispian Olver, Executive Director of the PCC, told this reporter that “a lot of the international partners … are looking to build a model [such as]in South Africa, and then expand it and replicate it elsewhere”.

“We’ve also heard the same from many of our sister developing countries, and they’re not looking to replicate what we’re doing exactly… but we’re acutely aware that countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Brazil, several African partners are all embarking on very similar energy transitions and they have to grapple with the economic and social consequences of those transitions.

“So, the thinking that we’ve had around the just transition is being picked up by many of these countries.”

Olver shared some of the lessons that South Africa offers to other countries. These include to:

- Be consultative

- Be inclusive

- Make use of forums such as climate commissions

A year ago at COP26, in what was hailed as a “watershed” moment for South Africa and international collaboration, a political declaration announced the mobilisation of $8.5-billion to accelerate South Africa’s move away from its ageing, polluting and unreliable coal fleet towards renewable energy sources. The declaration heralded the first step in developing a pioneering model for climate-focused partnerships and collaborations between developed and developing countries.

United Nations (UN) Secretary-General António Guterres, at the conclusion of the conference last year, said, “To help lower emissions in many other emerging economies, we need to build coalitions of support including developed countries, financial institutions, those with the technical know-how. This is crucial to help each of those emerging countries speed the transition from coal and accelerate the greening of their economies.

“The partnership with South Africa announced a few days ago is a model for doing just that,” the UN chief said at the time.

The model was formed after the governments of South Africa, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union – collectively known as the International Partners Group (IPG) – signed the political declaration.

The coalition of rich countries and South Africa became known as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). This partnership spurred the development of both the investment plan and a framework for how best to move away from coal in a way that doesn’t leave workers along the coal value chain – particularly in Mpumalanga – stranded and destitute.

On Wednesday, plans and pledges became a reality when South Africa signed separate, highly concessional loan agreements with the French and German public development banks, AFD and KfW, worth €600-million (R10.7-billion).

France and Germany are two of the partners in South Africa’s JETP, along with the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union. With associated interest rates for loans agreed at 3.6% and 3%, respectively, the loans are more palatable than the 8.9% the South African government would expect to raise an equivalent loan today in the open market.

With money headed towards the greening of South Africa coming from rich countries literally in the bank, South Africa’s JTEP model is being studied by other developing countries with similar fossil fuel dependencies and developmental imperatives.

Amar Bhattacharya, a senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development, housed in the Global Economy and Development programme at Brookings Institution, described South Africa’s investment plan as “precisely the kind of model that is needed to lay out an actionable plan”.

“It has got justice running through it … I want to emphasise something … this is a sustained effort; five years to start with is good, but it will require a generational shift.”

Lebogang Mulaisi, head of policy at the Congress of South African Trade Unions, was lukewarm about the JETP and its investment plan.

“It’s a start for a broader conversation around how to finance the transition … I’m not convinced yet … that we go deep into how we’re going to address ownership structures in South Africa.”

She said reskilling and upskilling are excellent, “but we have an ownership crisis in our country … and I just don’t feel we’ve addressed inequality decisively”.

Indonesia and India are two developing countries with similar coal dependencies at different stages of their transitions.

Dr Sandeep Pai is a senior research lead with the Global Just Transition Network at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). His expertise spans the political economy of energy transitions, coal sector dynamics, energy access and just transitions.

“Indonesia is very interested in multilateral financing to phase out coal long-term. India, not so much. India considers coal as a key energy security source. Generally, India is not interested in any deals focusing on coal phase-out or phase-down. However, both of these countries are in JETP negotiations with G7 countries. G7 and Indonesian negotiations are at advanced stages, but negotiations with India are going slow,” he told DM168.

Asked whether South Africa’s JETP can be considered a model, Pai said, “Yes, JETP partnerships theoretically could be a model for catalysing a coal phase down in India and even Indonesia. However, not the way it has played out in SA.

“India and Indonesia need to learn many lessons from SA’s JETP model. India and Indonesia need to develop investment plans … do their homework, identify projects they want to execute, and then negotiate JETPs with rich countries … I don’t think either of these countries has done their homework yet.

“[The] South African JETP model – although very relevant for India and Indonesia – won’t be meaningful for workers and the climate in its current form.”

Asked what lessons South Africa’s JETP experience offers, Pai shared his thoughts.

“In the arc of just transition, countries like the US are implementing just transition, SA is about to implement, and India and Indonesia are starting to learn about just transition. So, India and Indonesia have a lot to learn from SA, from how to run and engage various stakeholders, including unions, regions and municipalities in Mpumalanga, to concrete technical issues such as how to repurpose coal plants such as those being undertaken by Eskom.”

Dr Rahul Tongia, a Senior Fellow with the Centre for Social and Economic Progress in New Delhi, largely concurred with Pai. He is also a non-resident Senior Fellow in the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution. His work spans the entire gamut of energy and electricity.

He explained that while lessons can be drawn from the South African experience, the country’s JTEP is more accurately described as a “reference point” for India and other countries with heavy coal dependencies than a template or model.

“South Africa is heavily coal-dependent, more so for its power sector, but there are critical differences with, say, India, that make South Africa’s JETP more valuable as a reference point than as a template. Most South African coal power plants are decades old and thus close to the end of their life.

“In contrast, the median age of India’s fleet is close to just over a decade old.”

Tongia continued, “India’s high growth ahead (with much lower per capita emissions than South Africa) means it’s more important to focus on avoiding the growth of new coal than overly premature retirement of existing capacity.

“Older capacity can be shut down in phases as alternatives mature, but that will take time. Cheap finance will certainly accelerate the crossover, as will other support (technological, institutional, etc.).”

Sinthya Roesly is the Director of Finance and Risk Management at Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) – an Indonesian state-owned electricity distribution monopoly that supplies most of the coal-fired power to the country. PLN can be considered the Indonesian Eskom.

She acknowledged that while there were lessons to be learnt from South Africa’s experience, Indonesia needs to “look into every aspect of the transition” and that it is essential to be “cautious in early retirement [of coal power plants]… balancing all energy sources to support the economy”.

Roesly’s sentiments accorded with those of Gwede Mantashe, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, who, in a parliamentary debate on just energy transition, said, “Our transition cannot only be about reaching climate change targets. It must also address energy poverty, which includes lack of access to energy, unaffordability of energy, and electricity interruptions or load shedding.

“A pendulum swing from coal-powered energy generation to renewable energy does not guarantee baseload stability. It will sink the country into a baseload crisis.

“Africa is the least polluter of the environment, yet it is the most affected continent by climate change. Therefore, it is incumbent on the developed nations, which historically benefitted from industrial economic activities that polluted the world resulting in climate change, to finance our transition appropriately and adequately,” the minister said.

Amos Wemanya, the Senior Renewable Energy and Just Transition Adviser at Power Shift Africa, a Pan-African think-tank, also called for vigilance and caution.

He told DM168 that “if done right, JETPs could offer an opportunity for piloting transformative approaches to addressing aspects of the energy transitions – like early coal retirement – in a principled way. They can also potentially help aspiring oil and gas producers like Senegal choose climate-friendly development pathways.

“However,” Wemanya added, “JETPs could also perpetuate the continuation of a troubling donor-driven approach to climate finance that maintains unequal global power relations, picks winners and losers, and serves geopolitical interests. JETPs must be considered within the broader climate finance architecture and as a mechanism to put more and faster climate finance on the table, particularly from major historical polluters.

“It is also important to recognise that ambitious goals such as achieving just energy transitions in Africa will require solutions that lie well outside the boundaries of JETPs.”

Camilla Fenning, the programme lead on the Fossil Fuel Transition Team at E3G, an independent climate change think-tank, said, “The exact pathway from coal to clean will be different for each country”. But she added that the South African JETP model has increased collaboration and political buy-in and produced an Investment Plan.

“We now need this to lead to sufficient grant and concessional finance flows.

“The SA JETP will not be an exact blueprint – and too early to judge its success – but JETPs to follow can certainly learn useful lessons – both on what worked and what didn’t.” OBP/DM

South Africa’s R1.5-trillion energy investment plan

(This abbreviated Q&A was taken from a longer article by Onke Ngcuka. Read it here.)

What is the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP)?

It focuses on decarbonising and developing three sectors: electricity, new-energy vehicles and green hydrogen.

The electricity sector will see decommissioning of plants such as Komati, expanding and strengthening of distribution and transmission grids, and increasing renewable energy projects.

Coal-reliant areas such as Mpumalanga are prioritised, with R1.3-billion allocated for the transition to renewable energy.

The critical issue of grid capacity will be tackled with new investment. The second key factor is managing the social and economic implications of a “just” transition.

The motor vehicle value chain will transition to new-energy vehicles, with employment protected.

R128.1-billion has been set aside to become a leading green hydrogen exporter and improve port infrastructure.

What will it cost?

R1.5-trillion. The Presidential Climate Finance Task Team says there is a 44%, or R700-billion, funding gap.

Who are the partners?

South Africa is a pioneer for developing countries with the $8.5-billion in funding it secured at COP26 – via the International Partners Group (IPG), which includes the UK, France, Germany, the European Union and the US.

The plan is to bridge the 44% funding gap from various sources, including the IPG, other countries, the World Bank, the IMF and the private sector.

Does South Africa have the capacity?

There are doubts. But assessing capability and needs have been prioritised, alongside monitoring and evaluation.

Is this the final plan?

It has been put out for public comment. Suggested improvements are welcome.

Criticisms of the JET-IP?

Some say it does not yet reflect the priorities of local people affected by the transition.

There has been much criticism of green hydrogen, but a just transition will be difficult without the fuel.

Some people question the emphasis placed on electric vehicles instead of public transport, but preserving jobs in the motor sector is a priority.