BOOK REVIEW: Heroes of the Struggle – ‘Forgotten Bastards’ by Mzi Mahola (Mahola publishers, 2022)

Reviewed by: ROBERT BEROLD

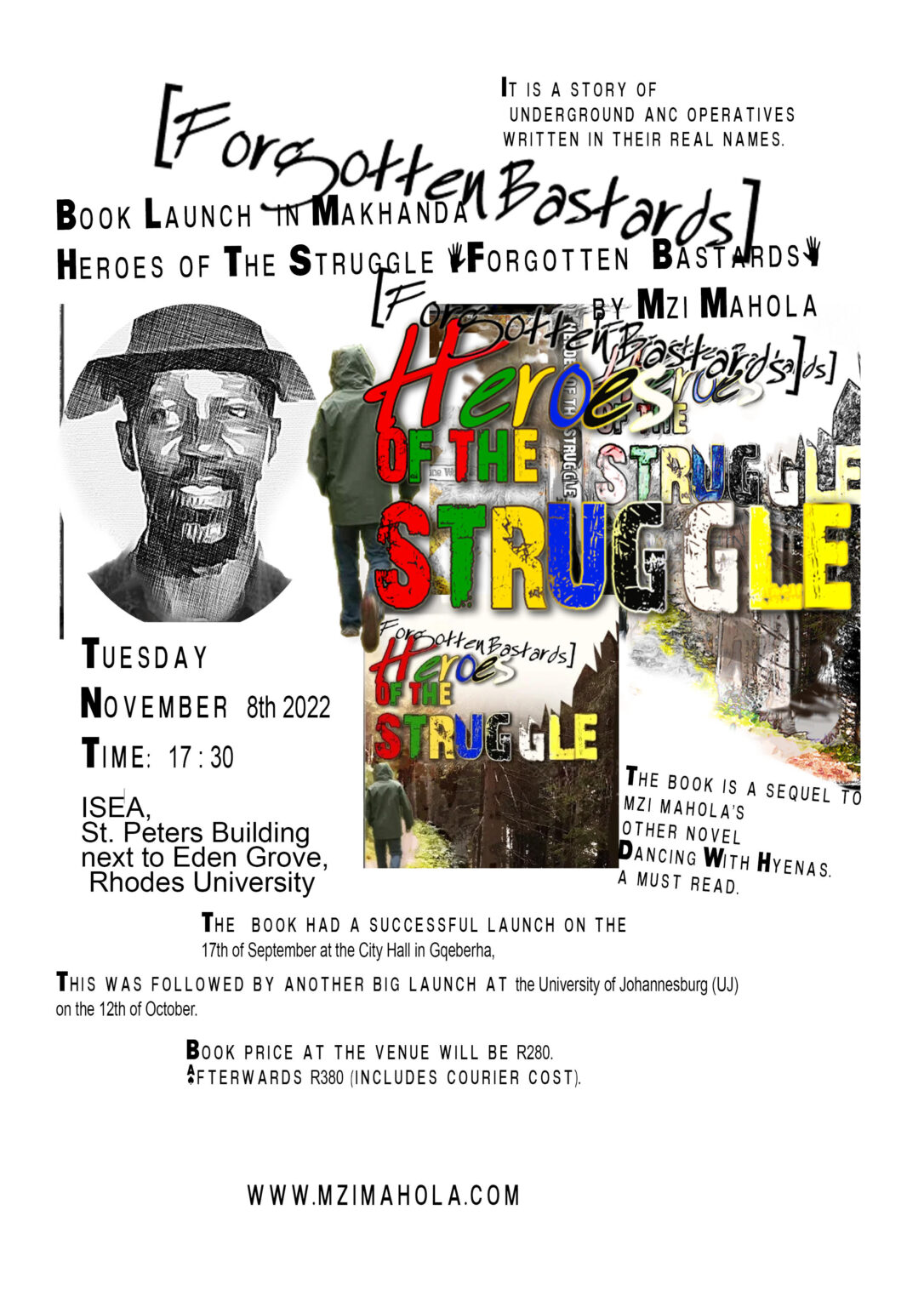

BOOK LAUNCH: 5.30 pm, Tuesday, 8 November, ISEA (St Peter’s Building, next to Eden Grove)

Mzi Mahola is one of the Eastern Cape’s well-known poets, writing in both English and isiXhosa. He ventured into the novel form in 2016 with a fictionalised version of his rural childhood and young adult life titled Dancing with Hyenas. This new autobiographical novel, Heroes of the Struggle, is set in New Brighton in the 1980s.

Lizo Khanya is a young man in his 30s and recently married when he is recruited into the ANC military underground, UMkhonto Wesizwe (MK). “We had no forests where our soldiers would be trained and from where they would go in and out to wage their guerrilla insurrection. Our geographic terrain was different. The enemy taught us to turn our townships into forests.”

In the forest of his township, Lizo and his fellow MK soldiers had to be at the same time visible and invisible. Visible because he had to continue as before in his job, his family, community, church and sports club (several of the MKs, including Lizo, were boxers). Invisible because of their clandestine activities, he needed a new name (he had two, Thabiso and Ngcayivuthwa) and a new identity. In his MK life, he had to act like he knew nothing about his other ‘normal’ identity.

It was the time of the young, radicalised school-age comrades coercing communities into burning down schools and government buildings, boycotting, bullying the older generation, and even killing people who resisted or who they considered to be informers, burning them to death necklace-style. The young comrades were themselves ruthlessly pursued by the police, who were later reinforced by the reckless community police known as kitskonstabels because of their inadequate training. Also very present and dangerous were the Port Elizabeth security police led by the sadistic Gideon Nieuwoudt, who were hunting, detaining and torturing the leadership of the UDF and SACTU, and killing MK soldiers when they found them.

Driving back from work one afternoon, Lizo finds himself driving through a gauntlet of stones hurled by comrades: “I was at the wrong place at the wrong time… Too late to react, I glimpsed something like a bird flying towards me. It flew through the open window and collided with me, hitting me on the right breast just below the collarbone. Like a winged bird, I immediately had difficulty breathing, as if a tight plastic bag was placed over my head… For a few minutes, I rested my head on the steering wheel. Nobody bothered to come and check, not even the guy who had thrown the rock. The rock was resting on the passenger seat next to me as if it was pleading innocence. After some time, long enough for me to see and drive, I started the car and drove home.”

Danger was everywhere, and knowing they could be discovered and captured, Lizo’s small cell of four men (women were considered unsuitable) were trained in traditional undercover work, communicating through signs and passwords, dead letter boxes, and even the use of invisible ink. They were taught to vary their routines and attire, to hide documents and firearms, to be careful what they said to other cell members or their families, and to give and take military orders. Initially, their training was in political education, political analysis, trade unions and colonial history, studying texts smuggled in from the ANC in exile. Their role was to be the channel between the leaders in exile and the UDF and trade unions. Their agenda was to make the country ungovernable.

The MK cell members were taken to community group meetings to give inspirational political messages from the ANC to activists, where they had to speak under their new names while pretending not to recognise anyone in the audience. They distributed pamphlets in taxis and public places. They hid weapons aND armed MK operatives from outside the Eastern Cape. Later on, Lizo travels to Lesotho for a month of political training and interaction with political exiles, some of whose behaviour seemed to him quite careless. The journey to Lesotho was itself full of danger, with hostile searches in trains and border posts. While in Lesotho, SA Police spies were closely watching the ANC. After his somewhat bewildering training, Lizo returns to New Brighton and his ‘normal’ job as an education officer at the Port Elizabeth Museum. He also returns to his life as Thabiso, the soldier, where he has been ordered to recruit more MK operatives and form new cells.

A real achievement of the book is the way it brings to life, often through tense dialogue, the chaotic atmosphere of the civil war in South Africa’s streets. Roadblocks were being set up all over, whether by police, street comrades, or even the volatile kitskonstabels. Lizo must adapt quickly to life-threatening situations and instantly decipher trust or betrayal. He survives mainly by teaching himself to stay calm and disciplined.

Lizo also has a connection with something he doesn’t share with his comrades, which he calls the Holy Spirit – the voice of God advising him on what to do. In one situation, sitting in his car with his cell commander and surrounded by armed police, his commander orders him to drive off at speed. The Holy Spirit tells him to stay put and go nowhere. This non-action saved both their lives.

On another occasion, setting out on foot to buy emergency medicine for his child-minder, Lizo ignores a white military officer’s order to turn back and starts running. He hears ‘Skiet hom. Skiet hom. Hy moet nie wegkruip, skiet hom!’ Lizo recalls: “When I turned to look back, the soldiers were still on their knees, taking aim. None of them pulled the trigger.” He has to return by the same route, walking towards the soldiers and waving his medicine bottle as a flag of peace. Again nothing happens. “I do not know what got into me that day, but the Holy Spirit would not let the army pull their triggers.”

The book ends with an episode about an MK operative Lizo and his wife were hiding and had to be smuggled out of the area quickly when the neighbours began asking questions. To me, this was quite an abrupt ending. Or maybe that was the intention? I hope somewhere else, or in another edition, Lizo will tell us how his MK cell was dismantled. What happened when comrades and enemies met in the 1990s in the bright light of day with their disguises gone? Whose minds and bodies were intact? Who was alive but remained wounded? How was it for them to be ‘forgotten bastards’?

Years later, Lizo or Mahola records some regrets: “In our struggle against the beast, we may have erred in causing disorder. Our children are now familiar with chaos, estranged from respect.” He adds: “Gradually, the word respect began to lose its meaning, and moral degeneration was surreptitiously becoming a culture as people became conditioned to this vicious circle. Their cry today is for that elusive Ubuntu, which will never return. The nation is reaping in tears.”

The book is obtainable from the author for R380 (including courier). Write to Apiwe Mahola at apiwe@mahola.co.za

A slightly shortened version of this review was published in City Press on 30 October 2022