By ZIMKITA LINYANA

Last Friday, travel journalist and author Marion Whitehead launched her latest book, Burchell’s African Odyssey, co-authored with researcher Dr Roger Stewart. The authors highlight the life story and contribution of the seasoned traveller, explorer, camper, hiker, and field researcher to science as we know it today, William John Burchell.

“The book reveals Burchell’s return journey from 1812-1815. This unrevealed part of the journey is the most significant one, as Burchell collected 75% of the specimens he collected here. Burchell disembarked in Cape Town in 1811, an eager 29-year-old naturalist with a romantic passion for science.”

“His achievements during the four-year trek across the Southern African veld in his ox wagon far exceeded those of other illustrious travellers to the Cape Colony (Eastern Cape),” Whitehead said. They felt compelled to write a book as Burchell never wrote about his return journey from the Klaarwater, along Graaff Reinet, the Zuurveld (Albany), Algoa Bay, Swellendam back to Cape Town; he only wrote about the outbound journey from Cape Town to the edge of the Kalahari – only a years’ worth of a four year trip in an ox-wagon!.

“The book looks at the highlights of the missing years and his most significant contributions to science.”

The Dictionary of South African Biography praises Burchell:

His work as a naturalist has never been equalled. His careful preparation, execution and completion of his objectives, detailed annotation and brilliant appreciation of nature set science a goal seldom achieved. Much of what he discovered has enriched the work of others.

Gordon-Brown A, Böeseken A. Burchell, William John. In: De Kock W, Krüger D, editors. Dictionary of South African biography. Volume II. Cape Town: Tafelberg-Uitgewers, 1972; p. 104-106. [ Links ]

Scientists are born, not made; this is what I believed until I was 18 years old. In high school, we were taught all about the ‘fathers’ of scientific fields, such as Charles Darwin, Gregor Mendel, Carl Linnaeus, Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, etc.

No mention was ever made of their educational background – in my mind, it was justified to assume they were born and not made scientists. One day a classmate asked my Life Sciences teacher, “Ma’am, what are exons and introns?” She replied, “don’t worry about that; it is stuff for scientists”. That response fascinated me a lot, it made me realize that maybe scientists can be made after all, and after a quick Google search, I found out what kind of scientists deal with ‘exons and introns’; it was biochemists. I went on to get a biochemistry degree a few years later, excited by the prospect of becoming a scientist. I remain fascinated by science and thinkers/pioneers like William John Burchell – becoming a scientist is my ongoing odyssey.

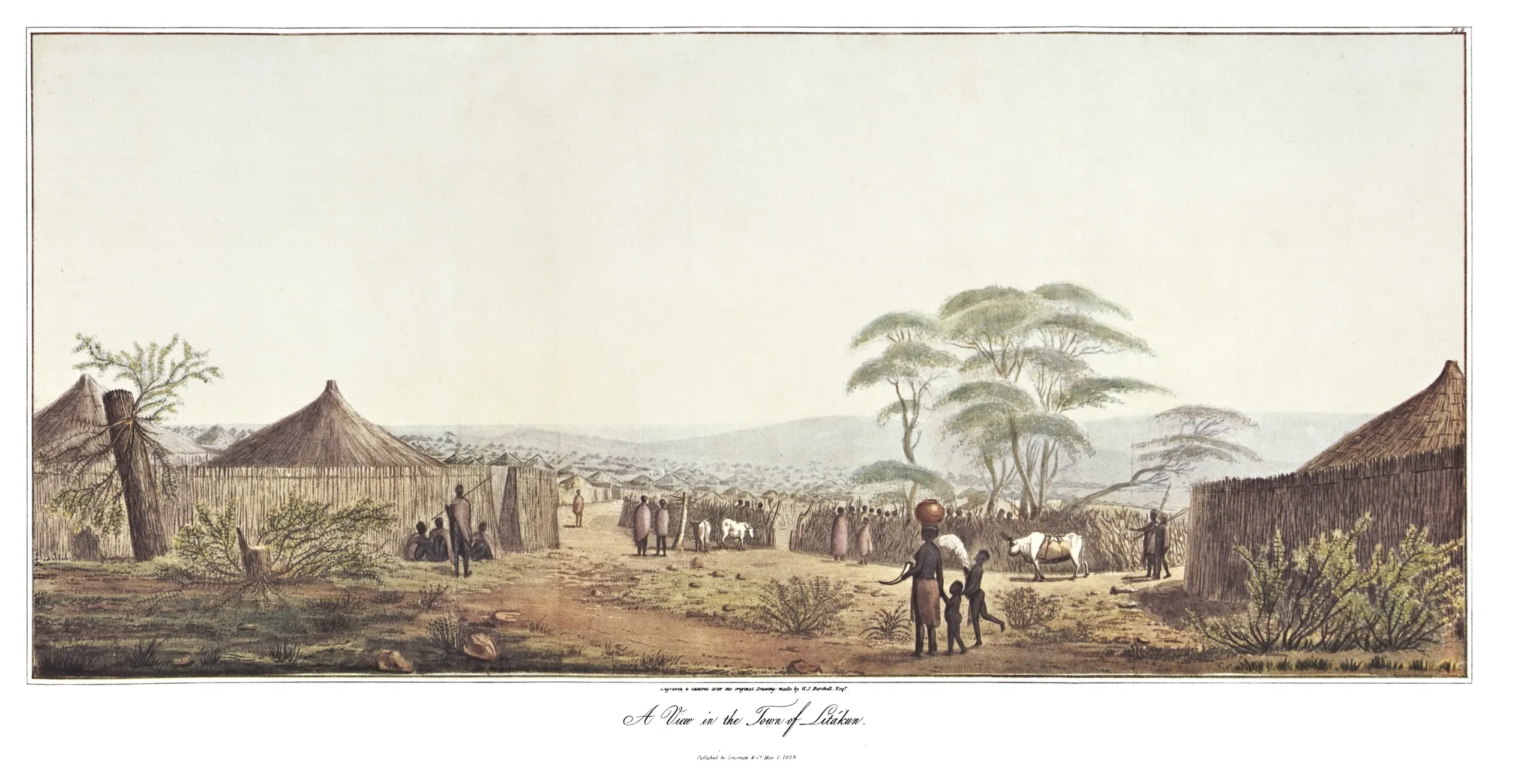

Englishman William John Burchell (1781-163) was a born scientist, a naturalist who had no science degree, nor was he beholden to British authority or a patron, like many collectors or scientists of the time. His was an independent mission, without much publication and thus least recognition – especially in his home country. According to the sleevenotes in the book, the sojourn was “funded by his savings and advances from his sole source of income, his family’s profitable nursery business”. Burchell left out a chunk of records from his African Odyssey. “He collected some 63000 specimens of plants, bulbs, insects, reptiles, and mammals – many not previously documented for science – and over 500 paintings and illustrations.”

This book is about a determined, intuitive self-starter who believed in his vision and showed us the possibilities of improvising. Burchell developed novel ways to preserve his collections; at times, he was without his plant press, but his novel techniques would keep collections in the same state for up to eight years.

The book reveals how he was a systems thinker, proven by how he travelled with a library of 50 reference books and what could resemble a mini laboratory or art studio, all shelved meticulously in his custom-made ox-wagon. Burchell purposefully omitted travel books from his library; such books would serve as guides.

This affirms his independence and intention to explore nature and people without bias or outside influence. In his writings, he said, “I wished to see things for myself”. This story also highlights how far we have come as humans in our research and development or innovation techniques, fundamental innovations that we take for granted today. To calculate the distance travelled, Burchell would count the rotations of the big wheel of his wagon periodically. To verify the date, he took astronomical readings in the evening skies and consulted astronomical ephemeris!

Burchell was a troubled man; he survived a romantic heartbreak when his girlfriend, travelling across oceans to be with him, jilted him for the ship’s caption! He then turned all his love toward collecting plants, animals, and insects. Eventually, he died by suicide.

What set Burchell’s odyssey apart from the conquests by colonists or “loot”-tenants of the time?

The book shows us how Burchell was unlike the missionaries, soldiers, lieutenants, and settlers. His relationship or engagement with the indigenous people is portrayed as collegial, humane, and communal, albeit without wisps of colonialism. Contrary to other explorers of the time and even researchers of today, in his books and records, Burchell acknowledged the contributions of the indigenous people in the process of collections, systems thinking, and thus knowledge production; the book captures this and provides brief bios of the first people of South Africa, the original and ultimate owners of all land in the Cape. Even though the ultimate recognition, even in literature today, inevitably goes to the Global North.

This is an important book for anyone interested in the history of science and its philosophy or even science journalism. The foundations and roots of science are primarily in the Global South. South Africa is the third most biodiverse country in the world. It is recognized for its endemism and is home to over 95 000 known species. This country, South Africa, only occupies 2 % of the world’s land surface area, and yet it is home to 10% of the world’s plant species and 7% of its reptile, bird, and mammal species.

Furthermore, it harbours around 15% of the world’s marine species. Endemism rates reach 56% for amphibians, 65% for plants, and up to 70% for invertebrates. Sadly, all this biodiversity is greatly endangered and under threat of extinction. Burchell’s work and the colonial project of exploring and collecting still reverberate in today’s knowledge system. This book makes for fascinating historical and even political debates. As a science journalist, I believe such stories must be told and interrogated.

This book is available online at: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.co.za/book/burchells-african-odyssey-revealing-return-journey-1812-1815/9781775848158