By MARION WHITEHEAD

Thicket plants are very friendly in how they all grow together, sharing light and water. And maybe that is why the people in this area are so friendly too, said Dr Rina Grant-Biggs, chairperson of Friends of Waters Meeting Nature Reserve, as she welcomed people to the first ever Thicket Festival in Bathurst at the weekend of 24-25 September.

“It’s a privilege to live among it; thicket is very special when you get to know it,” she commented.

The venue for the informative talks on Saturday at Pike’s Post, alongside the Ploughman Pub on the grounds of the Bathurst Agricultural Museum, was packed almost to capacity. The audience ranged from a retired professor of botany to local farmers and property owners wanting to know more about the plants on their land.

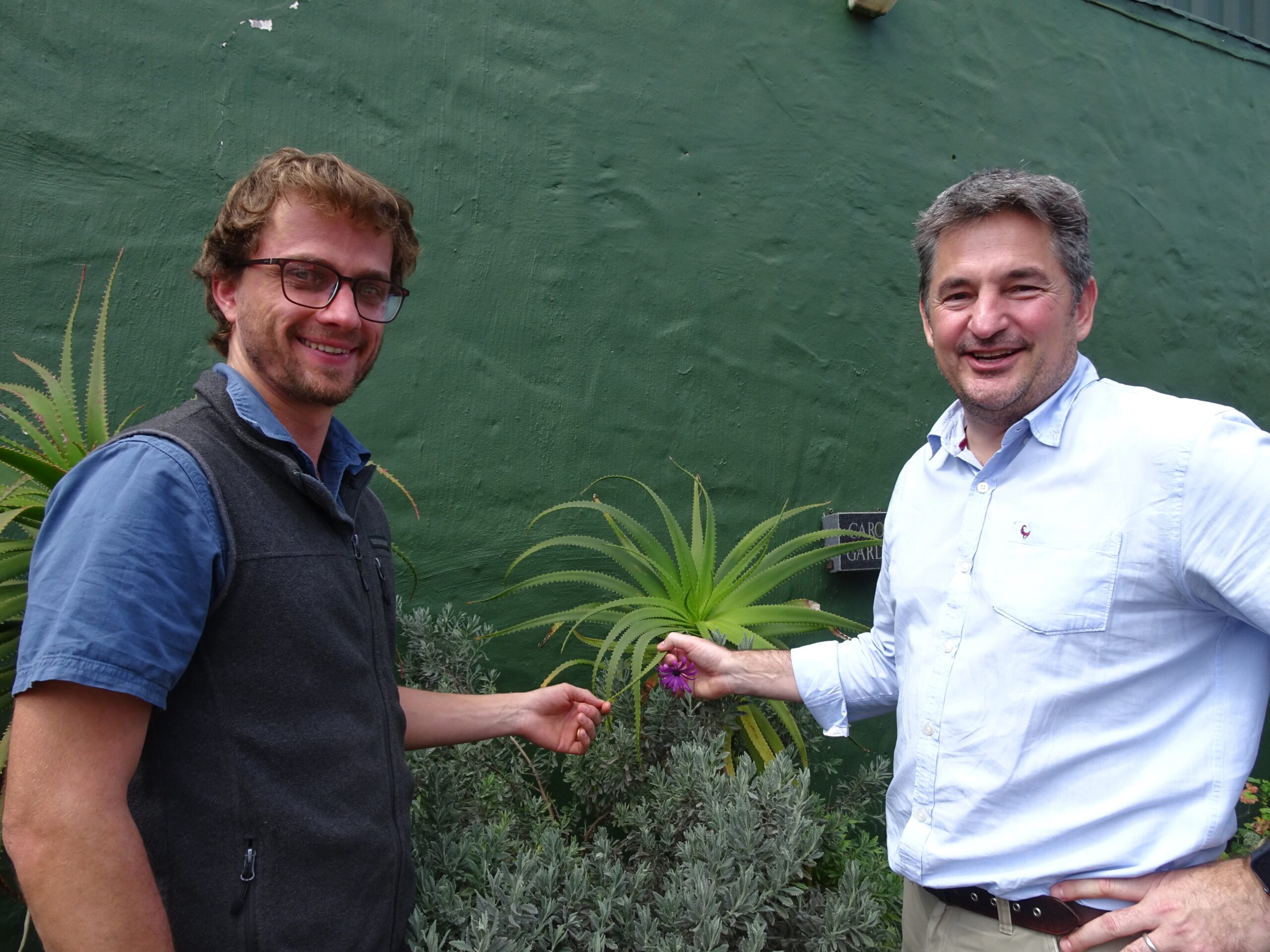

Prof Alastair Potts, a plant ecologist at the Nelson Mandela Botany Department, kicked off proceedings, shedding light on the different types of Albany sub-tropical thicket between Oudtshoorn and the Kei River. He explained how this ancient and very unique vegetation type manages to be so resilient and provide dense vegetation cover in arid areas, even in the face of prolonged droughts – a factor that will become even more vital as climate change pushes the limits of plants’ coping abilities.

Many of the plants are succulents, and their leaves act as mini water storage ‘dams’. Their leaf litter enriches the soil, and when there’s no rain, the plants release moisture into the soil to enhance microbial activity. In this way, other plants in the vicinity also benefit.

“Thicket operates like a dwarf forest in an arid area – globally, that is a weird phenomenon,” he pointed out.

Nicholaus Huchzermeyer of the Rhodes Restoration Research Group warned that thicket is disappearing, with large areas becoming degraded, despite legislation that protects virgin land from being cleared without a permit.

“Habitat fragmentation reduces ecosystem functioning, number of species and loss of climate change resilience, as well as resulting in less carbon sequestration,” he said.

Rivers provide a good indication of the condition of the catchment area, as sediments and nutrients washing into them adversely affect the water quality, and some species can no longer survive in it. The estuarine pipefish is an excellent example: it’s found only in five local estuaries: the Bushmans, Kariega, Kasouga and Kleinemonde East and West rivers, but is now critically endangered because of declining water quality.

“You could say the estuarine pipefish is the Bathurst area’s panda,” said Huchzermeyer, referring to the panda bear that is the global symbol of conservation in the logo of the World Wildlife Fund for Nature. “We can all make a difference. Clear your name instead of the bush,” he urged land owners.

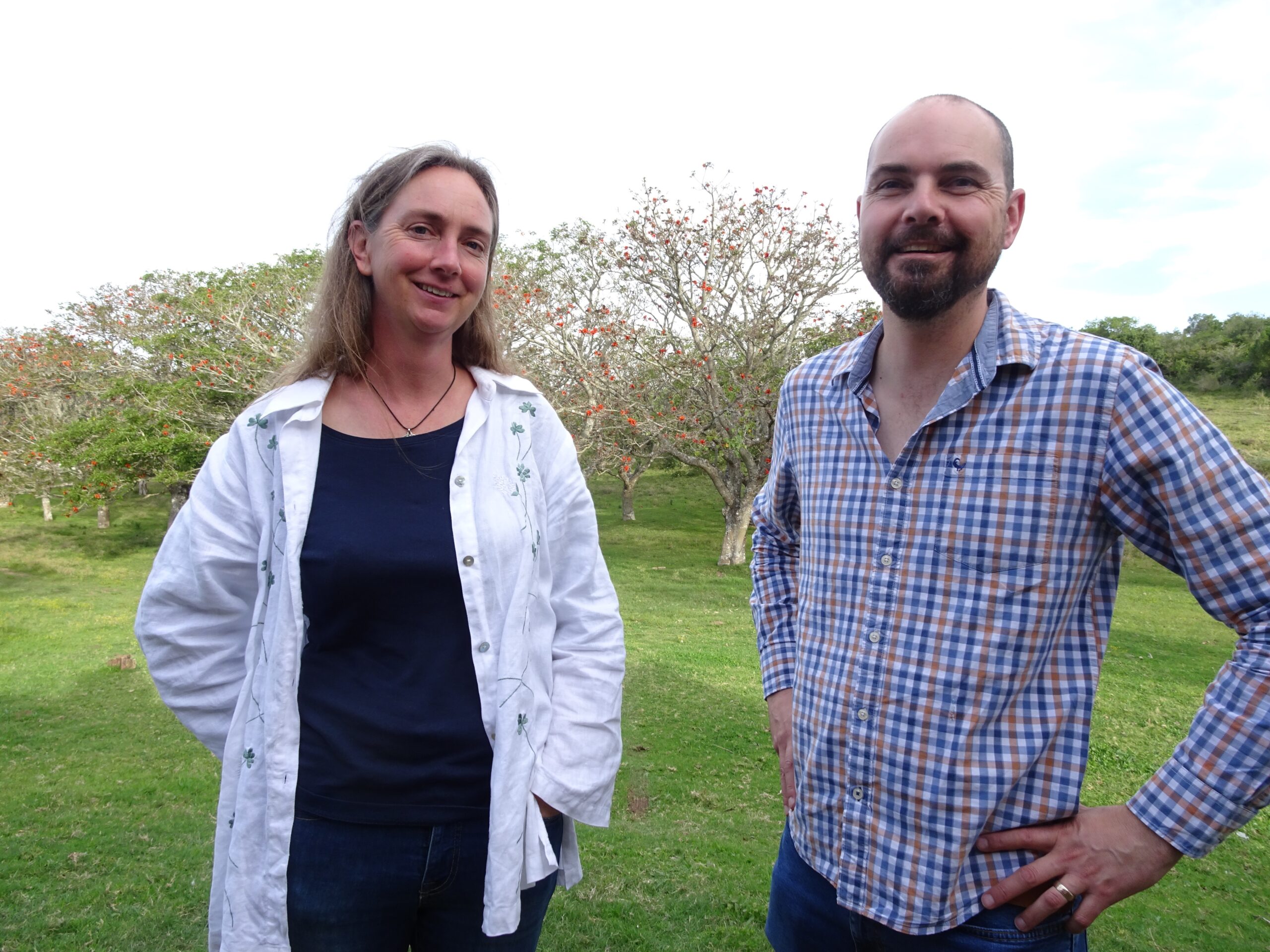

Michael Braack of the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment said the government’s Natural Resources Management programme was supporting research to find solutions, as well as projects such as Working on Water and Working on Fire. This created jobs while building capacity.

“Most funding is being spent on reversing degradation. That’s the current mindset, but it doesn’t achieve much. We need to avoid degradation and not allow the bulldozers to do the damage in the first place,” he said.

Sadly, thicket is the most degraded biome in South Africa. “The future rests on collaboration, building partnerships and working together. Without the farmers, we won’t be able to fix anything,” Braack said. “We must value this unique biome and conserve what we have left.”

Bathurst resident Serena Gess’s talk, ‘Into the Thick of It’, provided often unusual insights into the trials and tribulations that the 1820 British settlers faced after being dumped amid the wild thicket of Lower Albany. Their crops failed when rust and drought struck. The starving settlers had to learn which local plants were edible. One enterprising soul even crafted a fiddle out of wood from thicket trees.

Ben Smit, associate professor of Zoology at Rhodes University, spoke on the remarkable diversity of bird species in this area: 349 of South Africa’s 700 species can be spotted in the thicket of the river valleys. A surprising fact is that the Knysna turaco is more common here than in Knysna!

The extremely rare African barred owlet here is an example of a species that has become separated from the northern population for long enough to begin to differ in details of appearance. Ours are browner, very lightly barred and larger, and its calls are more chilled and less frequent. “So the Eastern Cape is potentially a laboratory of evolution in process,” said Smit.

The lantern parade through Bathurst on Saturday evening was a hit with families. Apart from the lanterns provided, many brought a variety of homemade lanterns to light up the thicket trees along the route from Lara’s Restaurant to the Pig and Whistle Historic Inn. The striking giant tortoise and warthog, made by Kate Peach, were real attention grabbers.

Sunday’s guided walk through the thicket on Bathurst Commonage with Monty Roodt, emeritus professor of Sociology at Rhodes University, was informative and fun. Trees in bloom included the wild pomegranate and the small bone apple, with its delicate creamy yellow flowers.

At the regular Sunday farmers’ market, Elizabeth Milne was kept busy chatting to visitors at the Friends of Waters Meeting Nature Reserve stall, sharing information on thicket plants for the garden and the medicinal value of many for the home pharmacy.

The festival ended on an appropriately chilled note, with Music at the Mill, organised by Historic Bathurst. Locals picnicked on the grass and quaffed their beverages of choice while listening to local musos sharing their talent in the midst of a wild thicket forest. It was a fitting way to wind up the first Thicket Festival in true Bathurst style.

For more information about upcoming events organised by Friends of Waters Meeting Nature Reserve, contact Rina Grant-Biggs at 079 519 5650 or email friendsofwatersmeeting@gmail.com