THEATRE: Hamlet

Review By ARNO CORNELISSEN

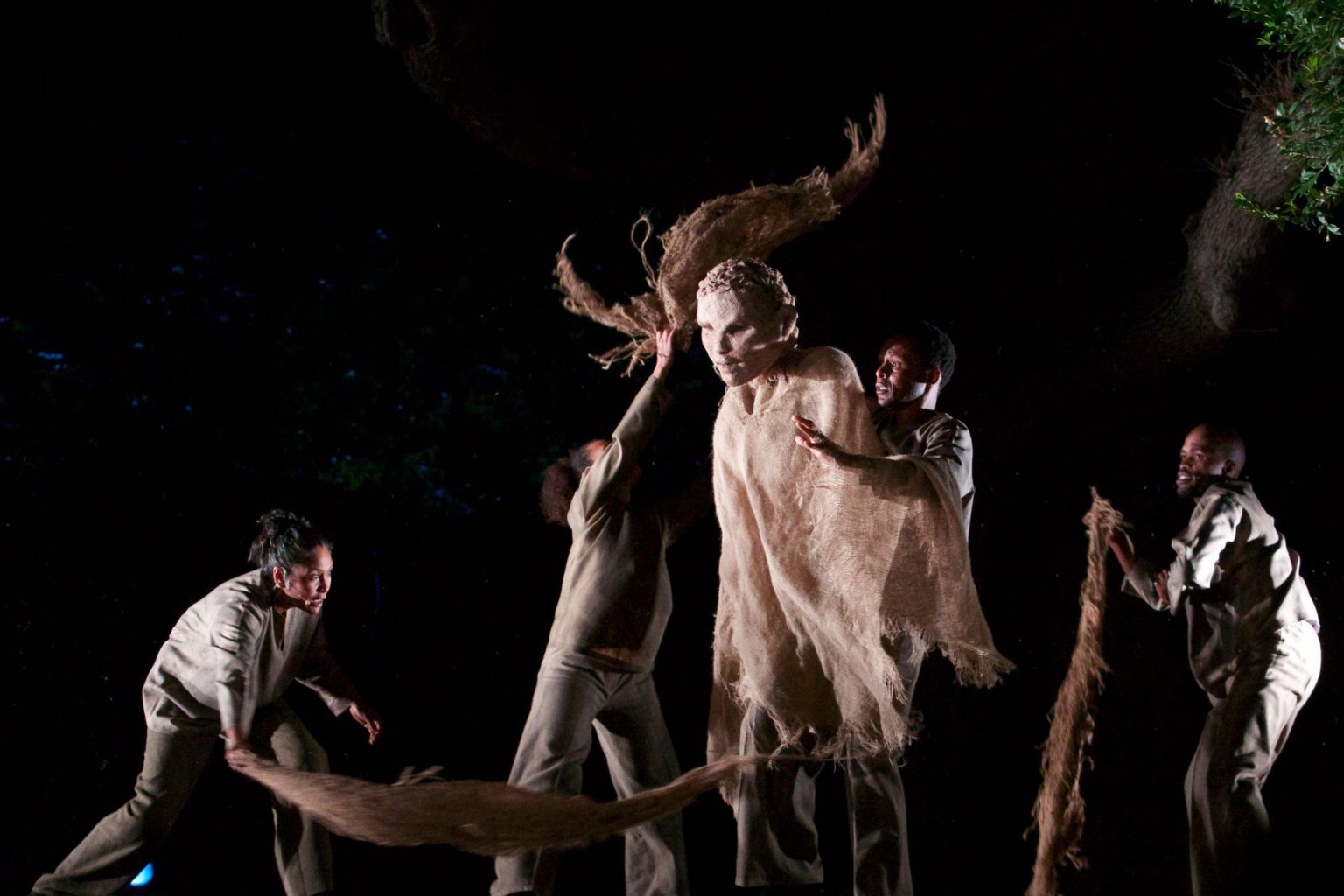

Show, don’t tell. The actors and puppeteers do precisely that, turning Shakespeare’s timeless play into a visually immersive performance, the expressive faces of the puppets as engaging and sinuous as rippling cloth. Hamlet, directed by Janni Younge, is skilfully innovative.

The choreography is eloquent, the puppets enhancing rather than constraining the actors’ work without burdening the stage with unnecessary gimmicks or dead weight. The focus is perfectly balanced between puppets and actors, at times moving as one and at others intentionally separating.

Set and lighting are wonderfully matched, with flowing material adorning the puppets, each controlled by actors. The loose material allows the actors to smoothly separate themselves from their puppets, splitting the characters’ personalities into multiples. They expunge themselves from the entity, experiencing and conveying their inner conflicts, before re-immersing themselves into a single being, transfiguring and adding complexities to form the protagonists’ personalities fully. The puppets are free from the constrictions of gravity, creating a fluid, ethereal performance.

The rendition of Hamlet’s deep personal conflicts, and the madness that swells up in him, are striking; their expression is re-invented. Two actors are used to voice and control the puppet that is Hamlet, uniquely reanimating the way his troublesome thoughts are depicted. This is especially powerful during his famous soliloquies when the visual puppetry allows complexity, conveying the schisms within his conflicted mind.

Lighting is an integral means of embodying the play’s supernatural and otherworldly elements. The puppets’ positioning and movements correlate perfectly as the illumination and shadows bring their facial expression to life. There are no eyes painted on or woven into their sockets, but the lighting angles allow our imagination free rein: we see their eyes, dark as they are, and the wrinkles and blemishes of their visage take on their own will.

Sound is given equal importance. It carries and crawls, shifting the tones and themes of the play. Embodying the ghost of Hamlet’s father, its eeriness extends natural boundaries.

Director Janni Younge has successfully contemporised the play. Hamlet’s friendship with Horatio is given new life by making use of Hamlet mocking Polonius: “Do you know me, my lord? / Excellent well; you are a fishmonger.” As laughter ripples from the audience, they bump fists. Although, Younge might have taken it a bit too far with Hamlet air-humping the all too big hole to fill – a miss-hit.

Further flipping the original script, she places the work within our continent through snippets of colloquial language and by shaping Laertes – the son of Polonius – along the lines of the virtuous warrior, intent on avenging his father’s death, done wrong by the treachery of the meta-metaphorical ‘royalty’. Younge also makes some heavy Shakespearean diction more accessible but, in doing so, unfortunately, loses some of the power and clarity of the text.

Shakespeare’s works are known for their immaculate poetic essence. Younge verges on not giving this aspect enough justice and power, but in the balance, the force behind the spoken word is given focus through Andrew Buckland as the voice of Claudius and Mongi Mtombeni, who is but one of Hamlet’s voices. Some of the Bard’s words are lost by some actors running too fast through the text, a perennial error in Shakespeare productions.

The state of Denmark is read as pitiful South Africa: when there is a dysfunctional royal family, it is reflected in the state of the state.

“Which dreams indeed are ambition; for the very substance of the ambitious is merely the shadow of a dream. / A dream itself is but a shadow. / Truly, and I hold ambition of so airy and light a quality that it is but a shadow’s shadow. / Then are our beggars’ bodies, and our monarchs and outstretched heroes the beggar’s shadows.”

Our ‘royal family’, the ANC, is crumbling, the effects visible on ground level. The powerful are too caught up in their own ambition to pay attention to the people who have entrusted them to rule.

We have been robbed of power — quite literally. Loadshedding cut this intriguing and wonderful adaptation of Hamlet nearly in half, removing the crucial sound and lighting required to suspend disbelief, ripping us out of our immersion in this extraordinary work. It was an ironic underscore.