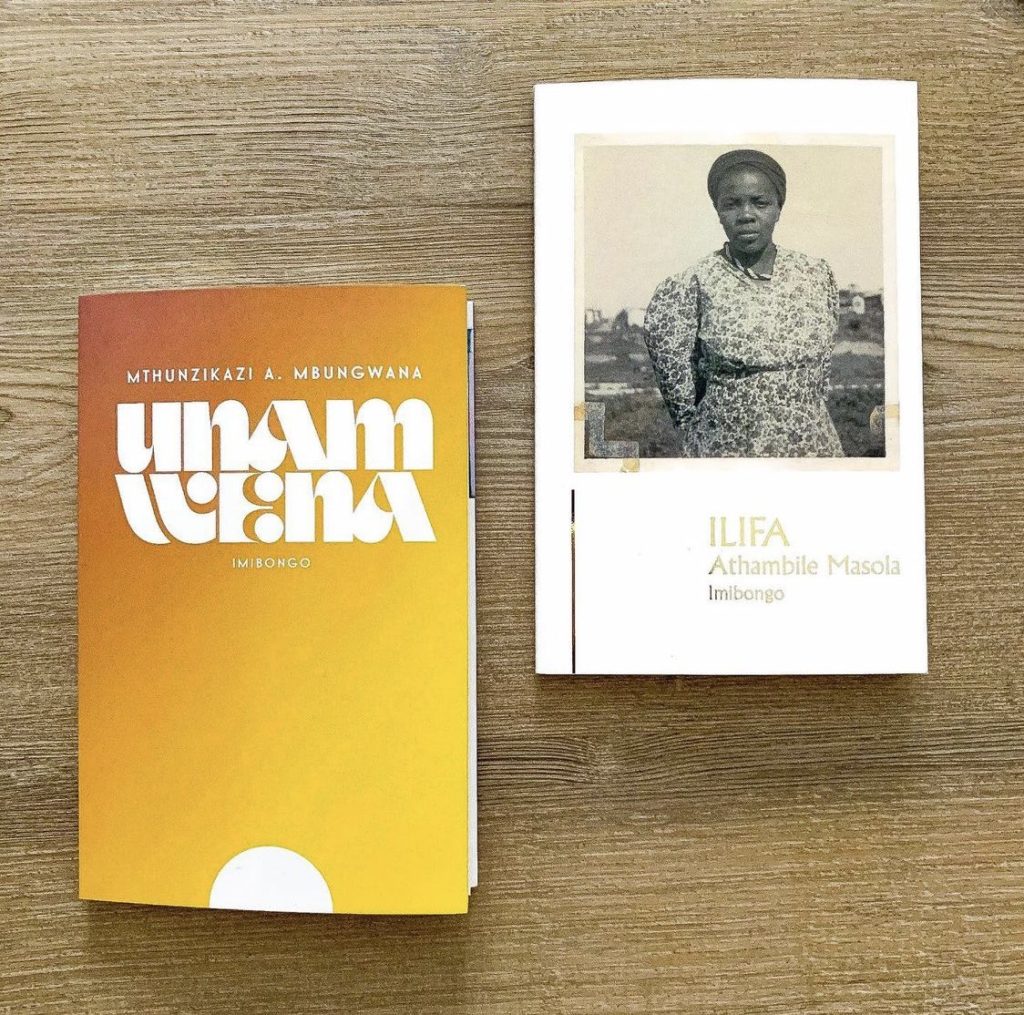

Reviews: Unam Wena by Mthunzikazi A Mbungwana and Ilifa by Athambile Masola

By Dr LUKHANYO MAKHENYANE

Reading Mbungwana and Masola’s poetry anthologies is like visiting a village after spending two decades in industrial cities. The moment you disembark and step out, your smiling face is greeted by a breath of fresh air that has been social distancing for the past twenty years. By this time, your lungs can tell you are in a different zone, and you can feel them taking huge gulps of fresh air. I had this kind of experience in reading Unam Wena by Mthunzikazi A. Mbungwana and Ilifa by Athambile Masola.

Having read a lot of poetry about love, life and human experience, Mbungwana and Masola expand on these themes in a whole new way. In poems like ‘Imilebe Yethu’, ‘Unam Wena’, ‘Asithethi’, ‘uBhospelithi Wam’, ‘Ukuzihluba’, Mbungwana uses shades of creativity to defend her thesis statement that love can be enjoyed by same-sex lovers as much as every other lover enjoys it. The way she unravels in ‘Imilebe Yethu’ takes us into a steamy session of same-sex lovebirds. In the last stanza of this poem, she uses a word, “Siyafikisana” (We reach orgasm), that reveals woman-woman intimacy can achieve what most men fail to do to women in their lifetime.

On the other hand, Masola dedicates a section of 24 poems to the universal theme of love. To those who lack self-worth and shy away from self-love, Masola has special messages for you in poems like ‘Izwi Elidala’, ‘Imvuselelo’. The images of spoons in a drawer (in ‘Amacephe’), tumour in ‘Intliziyo’, stars like sugar on black cloth share vivid pictures of intimacy with us. On pages 60 and 61, Masola invites us to her world of love by using lines independent of each other to define love. She uses lines like, “Uxolo va” (I am sorry), “Ubuye nesonka” (Bring back bread), “Ndicela undibase-e intloko” (Please base my scalp), “Urhalela ntoni” (What are you craving?), “Undiqumbele” (Are you angry at me?), to reveal the practicality of love, as love is a verb.

If you think the theme of love has long been exhausted in poetry, I dare you to pick up these two books and experience a breath of fresh air. Who knows? Maybe you will be inspired to write your own love poem, because love continues to be beautiful, and it is inexhaustible.

The poetry of Mbungwana and Masola braves critical issues that have been tagged taboo to talk about among amaXhosa. They are not afraid to speak of issues that need to be sanitized and cleansed of their impurity in our societies. In 2021, they refuse to accept the unrealistic “norm” of categorizing women as secondary citizens. Masola opens her anthology with the poem ‘Umyalelo Wentombi’ and lists all that society commands females. She forces the reader to critically question why do we rarely hear equivalent commands to males?

In this first section, Masola calls for women’s freedom from societal norms that still bind them. In poems like ‘Isaziso’, ‘Wakrazulwa’, ‘Incoko’, she paints the hardships of being a woman, and you get to understand why she encourages herself with women voices of the past. As they say to her, “Ningavumi silityalwe”, “Ningarhoxi”, “Ningatyhafi”, you hear her muted response, “Asizovuma nilityalwe”, “Asizokurhoxa”, “Asizokutyhafa”. Masola fights for her freedom as a woman with her pen. She calls on society to critically think about the patriarchal norms they espouse while sacrificing women at the altar of being normal. It is time for the ‘new normal’.

As you marvel at Masola’s fight for freedom, you hear Mbungwana’s voice crying for liberation to be who she is. She shocks her audience by revealing that society ought not to be surprised at the sexual orientation of those who choose same-sex relationships as this is not new. In poems like ‘Isingqala’, ‘Ameva’, she assaults society’s intolerance with lines like “Ndiboniswa amaxhegwazana amabini etshiswa ngepetula” in ‘Isingqala’. In ‘Umoya Wam Uyaphalala’, she uses a metaphor in a line, “Ukusukela la mhla wakhandwa iinzwane ziinyengane zentiyo” (From the day the toes were hammered by the granite of hatred), that calls for change on how the society treats people with sexual orientation different to them. Violence is uncalled for! Mbungwana shows how this intolerance manifests itself in shaming through names like ‘Nongayindoda’, which reduce people to things. In this poem, she shows how women who are called Nongayindoda are exploited, maligned and ill-treated.

In protesting against such behaviour, Mbungwana calls for a new way of thinking about people with different sexual orientations in this anthology. She reasons with the audience, arguing her case without imposing it on anyone. Even though you might not support such a lifestyle, you will enjoy listening to her side of her story – it’s a breath of fresh air. In her protest, she uses a two-pronged analogy – she protests against the abuse of women while questioning intolerance of a practice that has been among amaXhosa for too long.

I will be amiss if I do not whet your appetite with Masola’s last section. I had chills reading it as she paints a gloomy picture of dashed dreams and hopes of South Africans after freedom. She dares to call freedom in South Africa shit in the poem titled ‘Ikaka’; yes, ikaka. The same theme of disillusionment runs through poems like ‘Edolophini’, ‘Khwela sisi, Uya Phi?’, ‘Apha’, ‘Ilifa’. How can I forget the one title ‘Umongameli’, as it paints her disappointments with how President Ramaphosa responds to Gender-Based Violence? The last stanza of the poem that bears the book’s name, ‘Ilifa’, reads: “Andinamfuyo/ Andinandlu/ Andinamhlaba”, simply put, I have no inheritance. Indeed, this is a breath of fresh air that you sure want to breathe.

If you do not believe these two anthologies are a breath of fresh air in IsiXhosa poetry, look at the external structure of most of these poems, it’s something you don’t usually see in IsiXhosa poetry. What is amazing with the external structure of their poems is how it is not used for unique structure’s sake. It is used to emphasize the themes of these poems. You will find some poems starting on the right margin, in the middle or left margin and then move all over the page, showing the ups and downs of life. Some of their poems have no punctuations, and the lines do not begin with a capital letter; at the elementary level, one would say they are using their poetic license. As you dig deeper into the mines of their poetry, you realize it’s a call for freedom, its protest against abuse, intolerance and injustice against women. It is a message to go against the popular belief of oppressing women. It is a message that speaks in thunder tones, saying it is enough.

These two anthologies are a happy hunting ground for researchers and academics. They deserve a seat in any University curriculum, as they are a breath of fresh air in IsiXhosa poetry. They can be compared with IsiXhosa poetry of the past or contemporary poetry of other languages across the globe. The voice of women which oozes from the goldmine of their poetry calls for the attention of researchers. The literary devices used, the new images formed, the new terms employed are hard to pass by for one with a critical eye.

You have been breathing old air for some time now, and you will agree with me that your lungs can do with a breath of fresh air. Here are two anthologies that will take you besides the sounds of river water navigating their way among stones, that will take you where the birds sing morning songs of a new day, that will take you where the trees, flowers and grass usher in fresh air for the villagers.

Enjoy!

Mthunzikazi A. Mbungwana is a part-time teacher in the Creative Writing Department at Rhodes University, where she also received a Masters in Creative Writing in isiXhosa. Her writings focus on themes of home, dreams, and everyday black queer life.

Her work has been published in numerous literary journals and anthologies, such as New Contrast, Atlanta Review, Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets 2008–2018, and To breathe into another voice: A South African Anthology of Jazz Poetry. She was born in Upper Indwe, Cala.

Athambile Masola descended from amaGcina and amaBhele, grew up in East London. A Mandela Rhodes Scholar, Masola researches the literary careers of historically ignored black women writers.

She is the founder of Asinakuthula Collective and a lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Cape Town. Her work has been published widely in journals, newspapers, and online. This is her first collection of poems.