Rhodes University 1904-2016, An Intellectual, Political and Cultural History by Paul Maylam

Institute for Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University (2017)

R220/ R295

Rhodes University plays a crucial role in Grahamstown – first because of its sheer size and therefore its physical, social and economic impact on the town. And then, in more recent years it’s had a growing impact through partnerships with Grahamstown schools to support local educators and helping solve the problems of the town, and the country.

Grocott’s Mail reported on the early local stirrings of #RhodesMustFall, and then the two rounds of #FeesMustFall, louder than ever calls for transformation and decolonisation and the stand against a patriarchal culture that #RUReference represented. We spoke to people across the city – residents, businesspeople, workers, students and academics and the police – and most had two things in common: they were traumatised, and blindsided.

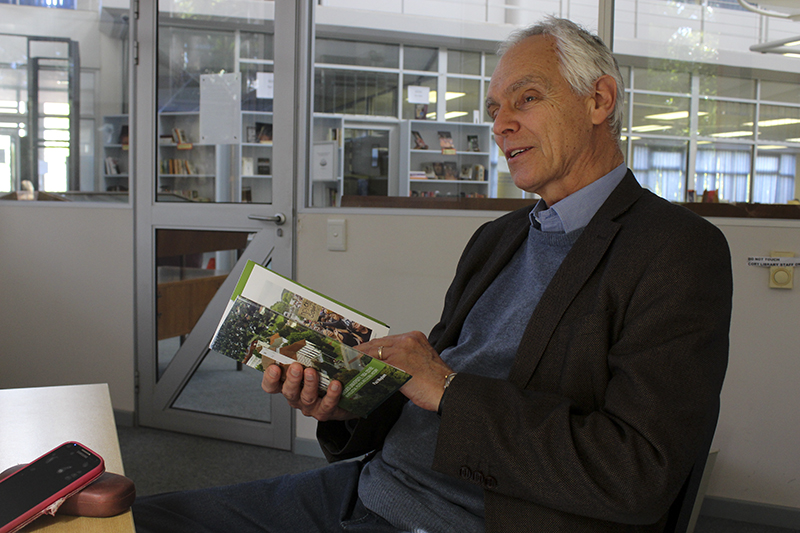

Historians, like journalists, must choose which parts of a very big story to tell, and by Paul Maylam’s own introductory disclaimer to Rhodes University 1904-2016, An Intellectual, Political and Cultural History, he doesn’t claim to be objective.

The product of over four years of research and writing, the book provides a critical account of Rhodes’ 113-year history.

“There is much in the university’s history that is worthy of celebration, but there are aspects of this past that reflect poorly on the institution,” says Maylam, Professor Emeritus in the University’s Department of History. For example, some critics of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the late 1990s had pointed to the failure of the university sector to make any submissions to the commission.

Early in the first chapter of his book, Rhodes University 1904-2016, Paul Maylam describes the debates that happened about ‘Founding an Imperial University’ and readers will feel thoroughly at home with the description of Grahamstown at the beginning of the last century:

Its sanitation is defective; its supply of potable water is poor… the pursuit of the fine arts is not much in vogue; practical demonstration of the many-sidedness and fertility of modern civilisation is impossible, and the social atmosphere is somewhat overcharged with that jejune, old-world ecclesiasticism, so often the cause of loss of faith in the young and the sense of proportion in the middle-aged.

That Rhodes University had its origins in the political programme to bolster and feed British imperialism and the colonial project is set out within a few pages, right at the start. Factors persuading the Rhodes trustees to fund it included the wish to counter the strong drive by the Stellenbosch based Afrikaans community to provide quality education for young people.

Maylam quotes then headmaster of Kingswood College EG Gane (the private schools were integral to the university’s foundations): “The Rhodes College is to imply Higher Education under the best of imperial influences.”

The Rhodes trustees were persuaded that “a college in the eastern Cape was ‘a necessity, educational and political’.

Maylam writes about student life through the two world wars and the Spanish flu epidemic, with the aim of student life in the 20s described in a 1927 edition of The Rhodian as “to be funny, to make humorous remarks and generally to indulge in hooliganism and rowdiness”. A dearth of interest in South African politics was another characteristic, according to a source quoted in Maylam’s account.

While Maylam describes the passing of a resolution in 1915 that staff should avoid party politics, he quotes a Council member saying in 1920 that Rhodes had to be “one of the buttresses and bulwarks of empire”.

A number of themes are covered in the book: the institution’s founding as an imperial university; academic life in the early years and beyond; the infrastructural development of the campus; the changing patterns of student life and culture; the politics of the university, with a particular focus on its sometimes undistinguished role during the segregation and apartheid eras; the roles played by anti-apartheid staff and student activists; sporting achievements over the years; and the ways in which the university has addressed the challenges of transformation in the post-apartheid era.

Accounts of racial segregation at the institution, gender discrimination (it was only in 1941 that women lecturers had to resign when they married), infrastructure and the genesis of NUSAS, dresscodes, the student press and a terrible feud in the Music Department that ended in a lecturer suing the University for defamation follow.

‘Complicity and Opposition’ deals with Rhodes during apartheid. While research across disciplines flourished, led by science, and departments grew, led by legends like Butler, Brink, Gruber, Bradshaw, Wilson, Nunn, Gledhill, Allanson and Woods, so did Rhodes’s debt. By the end of 1973 they owed R400 000.

Rhodes politics comes under the spotlight with a whites only student admission policy amended in the late 1940s to admit some black postgrads. In 1959 the government prohibited the admission of black students into white universities.

Student thinking in the 1950s, says Maylam, didn’t rock Rhodes’s apartheid-supporting boat. A 1952 meeting to debate the Defiance Campaign was shunned by most students.

But the Separate University Education Bill and Extension of University Education Bill saw a 1000-strong march through Grahamstown in protest in 1959. It turned out what they were opposing was not discrimination, but the loss of university autonomy to make that decision for themselves.

The 80s saw the rise of student politics, and students spies (think Olivia Forsyth); arrests, protests, security branch harrassment.

The role of the university administration throughout comes under the spotlight in ‘A colonial or liberal university?’

“During the apartheid era, racism was firmly institutionalised and entrenched in the whole legal, political and economic structure of the country, thereby making all universities and other institutions party to the racial order. Given this broader context it becomes impossible to absolve Rhodes of the charge of racism,” Maylam writes.

He describes outright racist incidents on the campus in the 80s, in contrast to the work of activist academics such as Andre Roux, Nancy Charton, Jackie Cock and Marianne Roux.

The entry of Centre for Social Development and an adult education programme allow a short discussion on amelioration versus transformation.

Maylam describes the focusing of political organisation on campus, including the women’s movement, which in 1993 formed a group called Women Against Rape (WAR). It was one of many student societies that began to take the lead in tackling areas of social injustice.

Non-racial sport found its place in non-campus collaborations until the 90s and 1987 saw the formation of the non-racial SA Tertiary Institutions Sports Congress (Satisco).

Part Three, ‘The post-apartheid era’, starts with ‘The transformation imperative’ and Chumani Maxwele’s March 2015 act of throwing poo at the statue of Cecil John Rhodes on the UCT campus, followed by #FeesMustFall.

Here Maylam goes on to provide historical background to the institutional and financial crisis of Rhodes and other South African universities. He asks to what extent Rhodes has pursued a transformation agenda since 1994.

“The university sector has in the post-apartheid era constantly faced calls for transformation, but there is contestation over what actually constitutes that transformation,” Maylam writes.

The book carries portrayals of some of the most prominent academics and students who have worked and studied at Rhodes. It recounts some of the key episodes in the university’s history; and it highlights some of the major trends and shifts that have occurred over time.

As protests about fees have reignited across the country, the former target Blade Nzimande finds himself the latest casualty in Zuma’s reshuffle war, and “state capture” rolls off the tongue as naturally as “transformation”, it could be time to note that the other difference between journalism and history is the advantage of hindsight.

It’s not over yet, Grahamstown, and Rhodes are bound to be rattled again – as history proves.

Soft-cover (R220) and hard-cover (R295) versions of the book can be purchased at Van Schaik Bookstore. For online orders contact Bulelani Mothlabane (b.mothlabane@ru.ac.za).