By Steven Lang

Australian palaeontologist Prof Kate Trinajstic visited Rhodes University earlier this month to help supervise local PhD candidate Ryan Nel’s thesis, which focuses on placoderm (armoured fish) fossils from the late Devonian Period. These fossils were recovered from black shale deposits on Waterloo Farm just outside Makhanda.

Trinajstic has devoted a large part of her research to fossils of placoderm fish discovered in the Gogo Formation in the Kimberley region of Western Australia – about a three-day drive from her base at Curtin University in Perth.

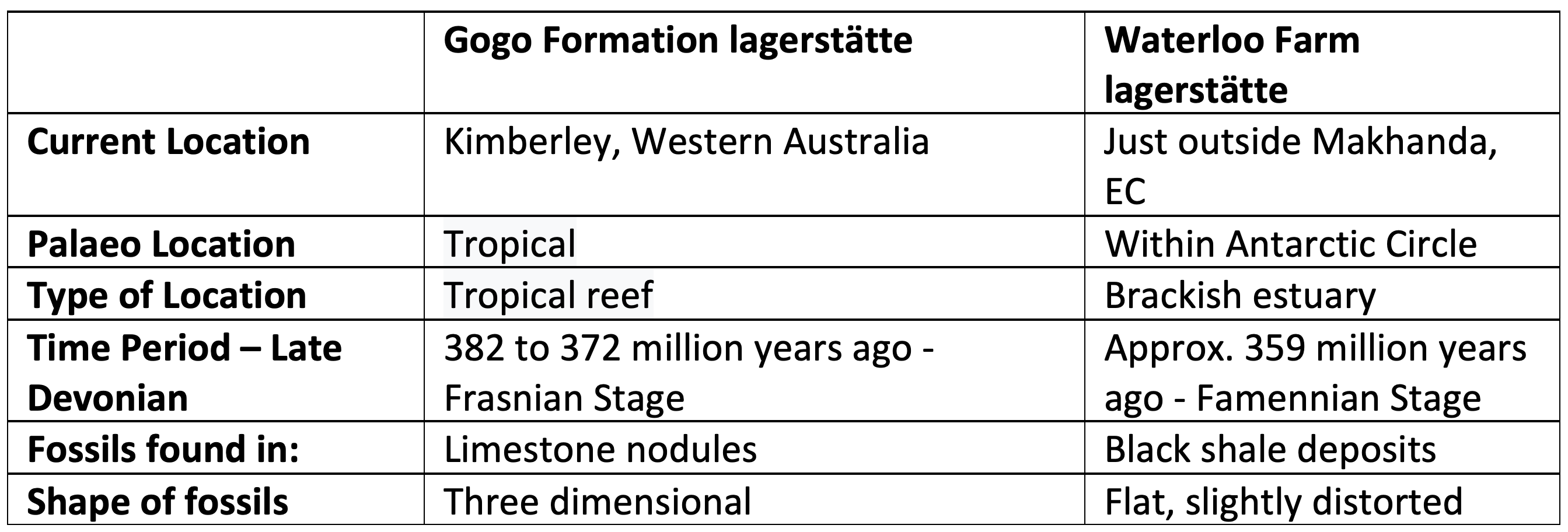

Although the fossils from the Gogo Formation and Waterloo Farm were both laid down in the Late Devonian Period, the Australian fossils are at least thirteen million years older and were deposited in different ways. Trinajstic explained that she is able to use her knowledge of the Gogo fossils to help Nel reconstruct the Waterloo placoderm fossils more accurately.

The Gogo fossils are three-dimensionally preserved ancient fish that occur in limestone nodules, which are found scattered across a plain. Trinajstic describes them as “Looking a little bit like hot dog rolls”.

She said, “Searching the nodules for fossils is like fishing with a hammer”.

The nodules formed when fish died in a tropical reef environment and drifted out to deeper water. She explained: “As it starts to descend through the water, it gets encased in a bacterial biofilm or a sticky mucus. And that holds the fossil together so that we actually get the entire fossil preserved”.

The bacteria work in two ways. They initiate the decay process and then provide phosphatase to gradually replace parts of the soft tissue with individual crystals of calcium apatite. This means that a single crystal replaces an individual cell, which is how minerals replace soft tissue. The whole animal is encased in hardened limestone, which stops it from being crushed, and so the fossil is found in a more or less three-dimensional form – after the nodules have weathered out of the softer limestone in which they formed.

Trinajstic said, “You can dissolve the rock and actually get the individual bones out and pretty much put them together like a model. So there’s not a lot of interpretation”.

Ryan Nel’s primary supervisor, well-known local palaeontologist Dr Rob Gess, has spent years excavating fossil-rich deposits on Waterloo Farm (near Makhanda), which were formed in a different way. Fish and other animals died in an estuarine environment that was within the Antarctic Circle at that time, about 359 million years ago. The carcasses then drifted to the bottom of a lagoon and were gradually fossilised as they were covered by fine, muddy sediment from the estuary. In this case, soft tissue was preserved by deposition under anoxic bottom waters, which arrested decay.

While both the Waterloo Farm and the Gogo Formation environments preserved bones and soft tissue, the local fossils have been flattened and sometimes scattered. Individual skeletons have, in some cases, been separated piece by piece, and the bones are intermingled with those of other skeletons. Sometimes fossils at different stages of development have been found in close proximity to each other – though these can be carefully separated and individual fish painstakingly reconstructed like three-dimensional jigsaw puzzles.

The Waterloo Farm and Gogo Formation environments complement each other as they both constitute lagerstätte – rare sedimentary layers with an abundance of unusually well-preserved organic remains. Such sites formed at different latitudes and in different periods give unique cameos of past diversity, assisting in interpreting the history of life.

Trinajstic said that when you have a lagerstätte, you have the preservation of a more complete environment. She explained that if you have a skeleton, some soft tissue and a variety of different fossils, “You can actually start to work out how those fossilised creatures interacted with each other and then how they interacted with the environment”.

She added, “You’re looking at a window of how an ecosystem lived rather than just how an individual animal lived”.

Comparing the two sites, Trinajstic said, “I suppose the greatest similarity is that they both preserve ontogeny”. Both the Gogo Formations and the Waterloo Farm have evidence of the different stages of development of a species. “So by using both formations, we’re getting a better picture of the morphology of this very early group of fishes”.