By Anga-Anganda Bushwana and Linda Pona

Exactly 30 years ago, the United Nations adopted World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) on 3 May, 1993.

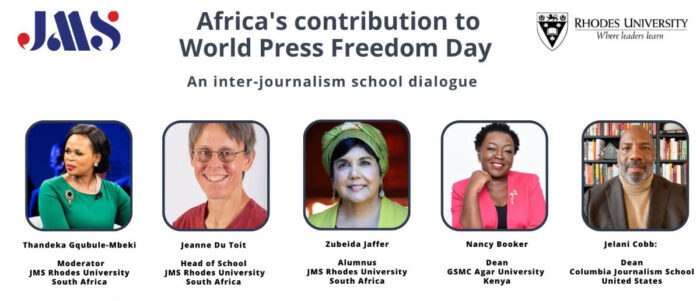

This year, the Rhodes University School of Journalism and Media Studies (JMS) launched an annual inter-school dialogue on press freedom on the African continent on WPFD, hosted by South African broadcast journalist, author, and academic Thandeka Gqubule-Mbeki.

The hour-long dialogue included scholars from South Africa, America, and Kenya. The discussion focused on the contribution African journalists made to founding WPFD. That is because the 1991 Windhoek Declaration formed the basis of WPFD.

The Windhoek Declaration is a statement of press freedom principles which declare that the press is free, independent and pluralistic. WPFD celebrates the fundamental principles of press freedom. This means that press freedom worldwide needs to be evaluated and that media are defended from attacks on their independence. This day also pays tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the line of duty.

According to pioneer and veteran in South African journalism, Zubeida Jaffer, Africa’s role in WPFD has been excluded from the international narrative. “Today the United Nations (UN) meets, but the concept note they have at the conference doesn’t mention that this started in Africa – and is completely an African initiative,” Jaffer said. “Our stories matter because we have good stories.”

Rhodes JMS lecturer Taryn De Vega said, “The end goal of the dialogue is to help journalism schools in Africa and internationally recognise the influential role that those African journalists and diplomats in the United Nations (UN) system had in establishing this important day.” She added that to this day, the UN had ignored this rich history of WPFD’s African roots.

One of the discussion’s main themes was colonialism’s legacy on the African continent. De Vega encouraged colonial scholars to interrogate themselves as Africans. “What does World Press Freedom Day mean to us, our continent, and our practice? To the way we exist in the world as journalists and practitioners?” She questioned.

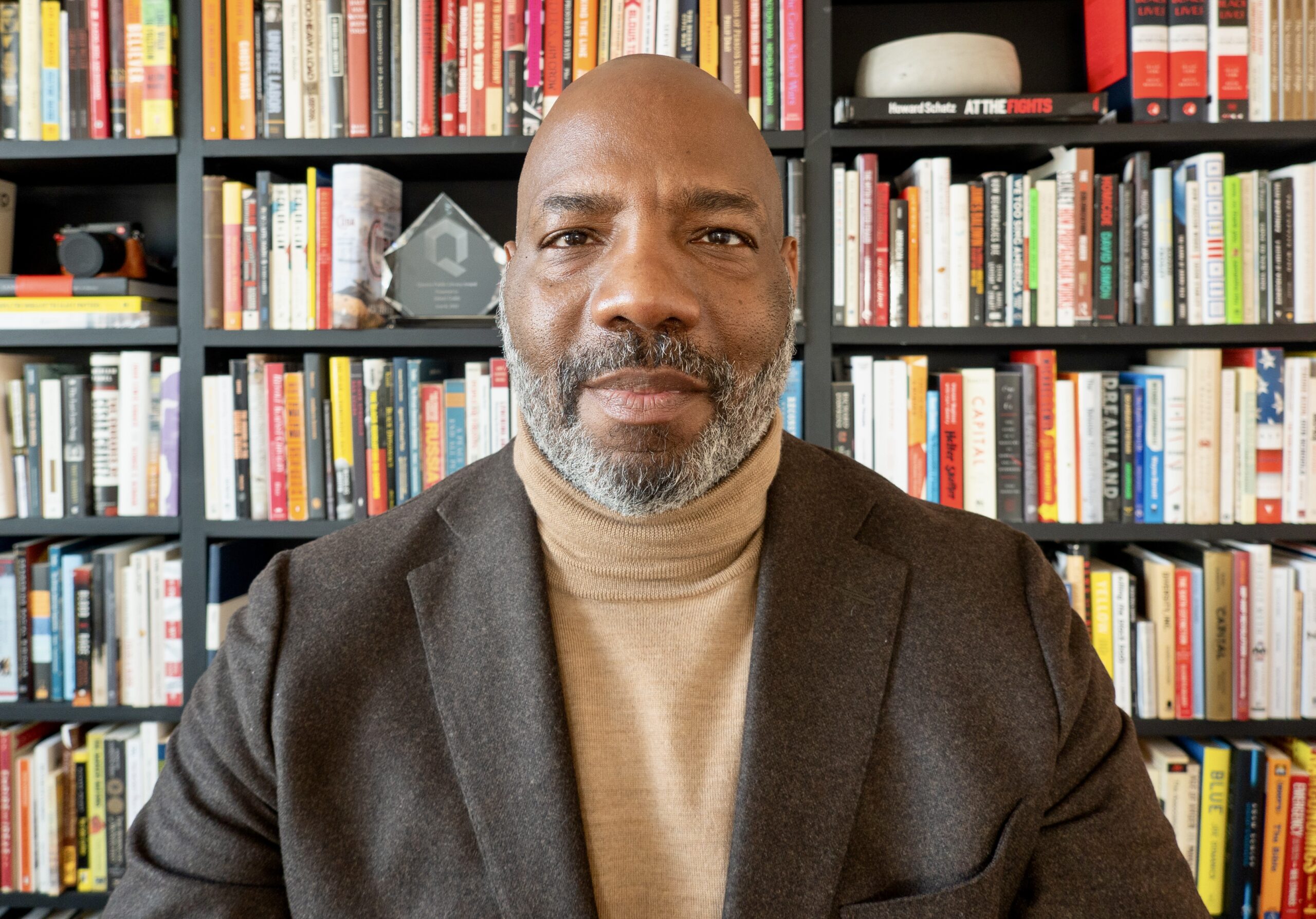

In response to De Vega’s questions, Dean at the Columbia University Journalism School, Jelani Cobb, suggests that history keeps repeating itself wherein the West “has never been inclined to tell of its indebtedness to Africa.” He referred to the post-Cold War era, where countries worldwide wanted press freedom, and the Windhoek Declaration catalysed WPFD.

JMS Head of School, Dr Jeanne Du Toit, added that perhaps the beleaguered newsrooms are because of the north and their global economy.

Another point of discussion that emerged during the dialogue concerned progress made on press freedom, thirsty years since WPFD first launched.

Rhodes JMS lecturer, Dr Chikezie Uzuegbunam, commented on media freedom according to the Nigerian or West African context. He suggested that media freedom has improved a bit because of new and emerging voices because of the rise of social media.

He does caution, however, that when we speak about press freedom but not media accountability. “We can’t progress without media integrity and transparency,” said Uzuegbunam.

Dean at GSMC Agar University in Kenya, Nancy Booker, concurs with Uzuegbunam that it’s the same in East Africa, where media is making progress, which is different to what was happening over two years ago.

So while there is some press freedom, there isn’t true press freedom.

Gqubule-Mbeki reminded the audience members that WPFD should be valued because journalists used to be jailed and died in the line of duty.

“Lest we forget those who have sacrificed for freedom,” she said.