By Steven Lang

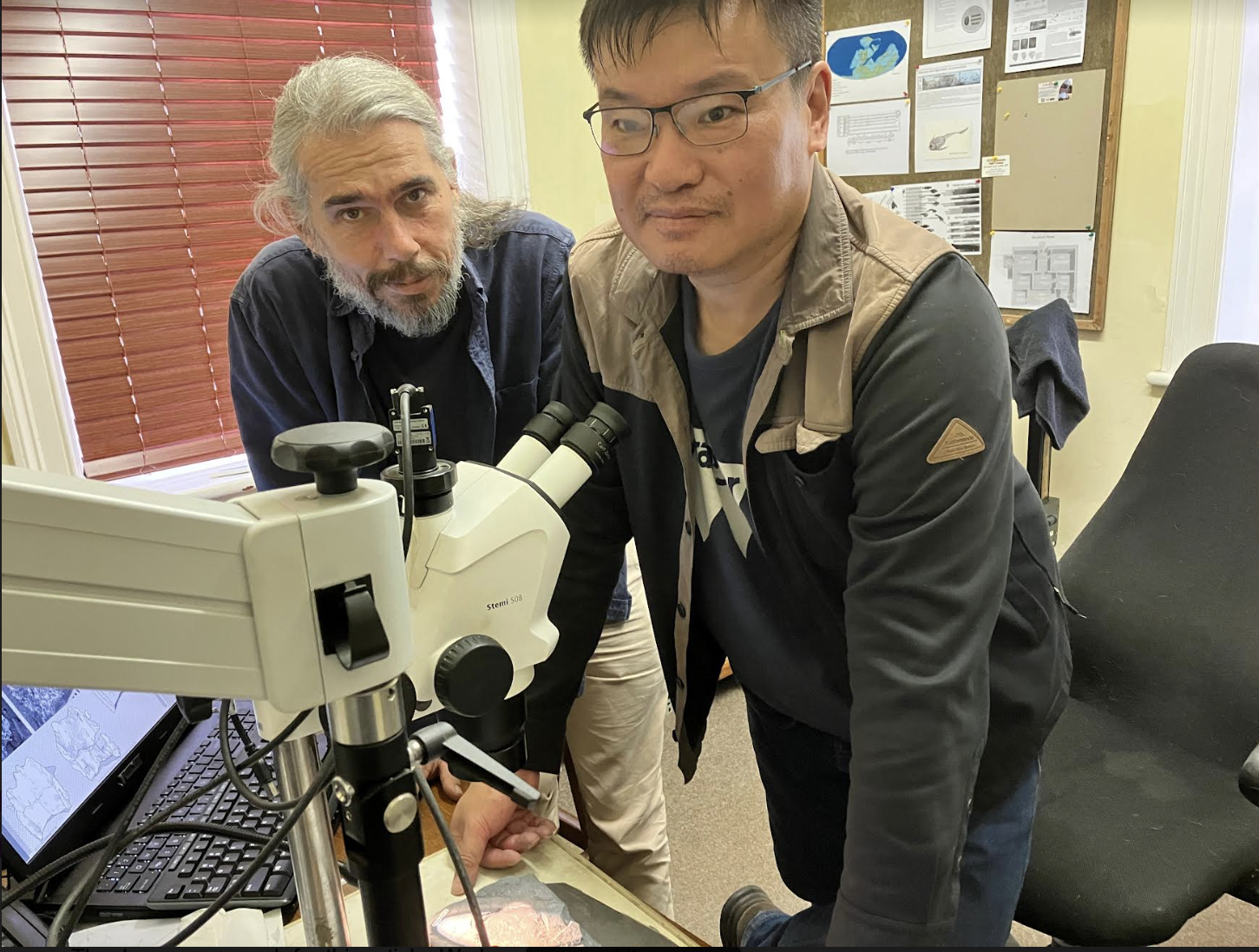

The unique, black shale deposits of Waterloo Farm have attracted yet another international scientist to Makhanda. Dr Brian Choo, a vertebrate palaeontologist from Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, is spending three weeks at the Albany Museum’s Devonian Lab studying fossils of a fish that lived in an estuary in this region about 360 million years ago.

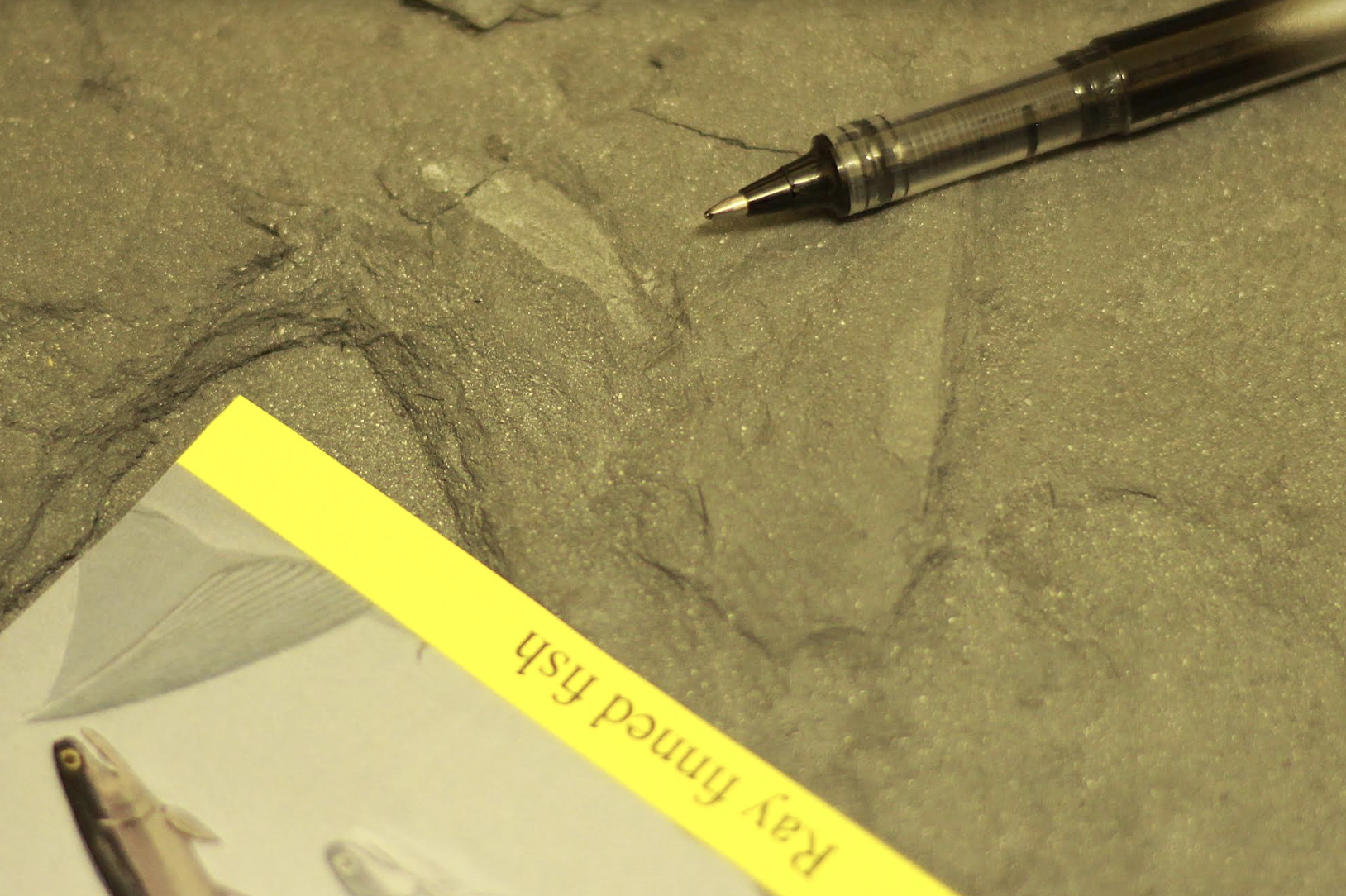

Choo said he came to Makhanda “to look at a new genus and species of ray-finned fish based on some wonderful material from the world-famous Waterloo Farm”.

Local palaeontologist Dr Rob Gess, who discovered the fossilised bones belonging to the as-yet-unnamed fish, has already made numerous discoveries of scientific importance from the shale deposits just outside Makhanda.

Ray-finned fishes are today a phenomenally successful group of animals, with about 27,000 species inhabiting just about every aquatic habitat imaginable. Choo explained that “Back in the Devonian Period, more than 360 million years ago – you wouldn’t have dreamed they would be such a successful group”. There are only a handful of fossil species known from good material dating back to that Period, “and it just so happens you have one here at Waterloo Farm”.

In the Devonian Period, placoderms (or armour-plated fish), and to a lesser extent lobe-finned fish, dominated all the oceans and rivers of the world. Placoderms all died out in the End Devonian extinction event after the Waterloo shale deposits were laid down, opening the way for ray-finned fish to rapidly dominate the whole world’s bodies of water.

Highlighting the importance of the local fossils, Choo explained that the majority of known ray-finned fishes of that time lived in warmer climates at tropical latitudes. At that time, sub-Saharan Africa was much further south, so the area we now live in was within the Antarctic Circle.

He said the Waterloo Farm species is one of the first known from the south polar region “and the only one from the South Polar region that is based on re-constructible material from multiple individuals”.

Gess added that from the South Polar region, “… there are only two other pieces of ray-finned fish from the whole of the Devonian,” and they are all extremely fragmentary, each consisting of a single incomplete bone from South America. His latest discovery is the oldest ray-finned fish ever found in sub-Saharan Africa.

Gess has published descriptions of his other fossil discoveries in prestigious journals such as Nature and Science, while Grocott’s Mail has carried several articles about new species he has described.

Choo and Gess have enough material from multiple specimens of different age groups to have a good idea of what this new species looked like. Almost all ray-finned fishes were under 30 cm long during the Devonian Period.

When they finish describing the anatomy of the fish, Choo and Gess will do a phylogenetic analysis to see where it should be placed within the ray-finned class.

Choo said they have not yet decided on a name for the new species but that “Once it’s fully re-constructed, and we can see if there’s anything particularly unusual about it, or anything that stands out about these fishes, we’ll think of something. Something appropriate, something cool sounding.”

When their research is completed, Grocott’s Mail will follow up with a detailed description of the new species and an explanation of its significance in the evolution of fish alive today.

Choo is not only a highly regarded palaeontologist but also an artist who does all his own artistic reconstructions of fossil fishes.