By Staff Reporter

The Rhodes Restoration Research Group (RRRG) has produced a new set of brochures on climate change and thicket restoration in the Eastern Cape.

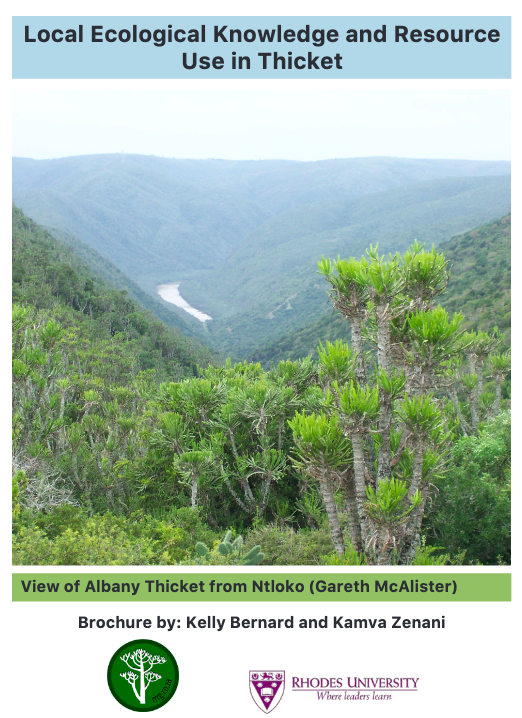

The Eastern Cape is the heartland of the thicket biome, which covers more than three million hectares. Thicket boasts an exceptionally high level of biodiversity and is capable of withstanding prolonged droughts, which makes it more resilient in the face of climate change.

During times of drought, Subtropical Thicket also provides forage for animals if it is not overgrazed. It helps replenish the water table and prevents soil erosion even in steep river valleys so that dams do not silt up.

Unfortunately, close to one million hectares of this Subtropical Thicket biome is degraded and needs restoration.

“Unlike other biomes, degraded Subtropical Thicket areas do not recover on their own and will stay in a degraded state or get worse with soil erosion,” said Mike Powell, director of the RRRG.

It is to prevent the land from becoming overgrazed by moving cows and goats to different parts of the farm before this happens, say RRRG interns Kelly Bernard and Kamva Zenani, who compiled the brochure series. “You can fill in dongas and plant indigenous plants to hold the soil together. Educating learners in school about the importance of protecting nature and the environment and getting the community involved in cleaning up rivers and the land is also important,” said Bernard and Zenani.

Spekboom (Portulacaria afra) has become the popular poster child for Subtropical Thicket restoration but is not the only vegetation that needs to be planted in order to restore the thicket fully.

There are 44 recognised types of Subtropical Thickets from five main groups: dune, arid, mesic, valley and mosaic. Local trees and plants are the best to use to prevent Subtropical Thickets from being degraded and to restore them.

The RRRG brochure series details a selection of useful plants, with details on how to plant them and what the benefits are. It is always good to first cover the soil with grasses, herbs and wildflowers to hold the soil together and increase water retention. Then you can plant:

– small plants that hold the soil together e.g. couch grass/kweekgras and sheep bush/ankerkaroo.

– larger shrubs that provide forage and enrich the soil e.g. spekboom/igwanishe.

– spiny trees and shrubs that make good hedges and windbreaks e.g. small-leaf honey-thorn/kleinblaarkriedoring, needle bush/speldedoring, blue kuni bush/bloukoeniebos.

– medicinal plants e.g. Aloe ferox/bitter aalwyn.

The brochures also give valuable advice on seed collection and storage, propagation and planting of these species.

When planning restoration projects, it is vital to be aware of local environmental knowledge and community resource use and practices. “This not only helps to protect nature and the environment but ensures that local practices and rituals can continue for many more years to come,” said Zenani.

For instance, many Subtropical Thicket plants and some animal products are used medicinally (amayeza esiXhosa) to treat lots of different illnesses and are also used in rituals (amayeza okwenza amasiko). Examples are African wormwood (umhlonyane) for treating fever and the roots of African potato (inongwe) for skin rashes.

In the Eastern Cape, Subtropical Thicket is referred to as ihlathi lesiXhosa and this is where many important community practices and rituals happen. Ihlathi lesiXhosa is respected not only for resources but as a sacred space to connect with the ancestors (izinyanya). A popular Xhosa saying explains this sacred space and connection nicely: uThixo ulihlathi lam – God is my forest.

“Restoring degraded Subtropical Thicket will provide food and water for animals and humans for many more years to come,” said Zenani.

“We are all in this together as we all depend on the land for our survival. We can all help make a difference,” added Bernard.

The brochure series covers the challenge of climate change and the biodiversity crisis, as well as gives a broad understanding of what Subtropical Thicket is and strategies to restore it.

The brochures are written in an accessible language and are available to download in English and isiXhosa.