The names Ian Player and Magqubu Ntombela are well known to an older generation of wild nature lovers. But will their legacies live on to inspire a younger generation of city folk increasingly estranged from the natural world inhabited by our parents or grandparents?

By TONY CARNIE, Our Burning Planet

Michael Charton’s latest tale, Leave some for the Honey Badger, is a narrative about the conservation of white rhinos and two men who played a central role in launching the African branch of the Wilderness Foundation 50 years ago.

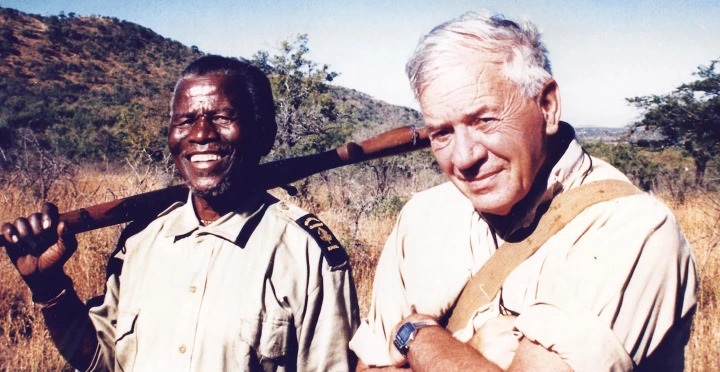

The names of those two men, Dr Ian Player and Magqubu Ntombela, are well known to an older generation of wild nature lovers. But will their legacies live on to inspire a younger generation of city folk increasingly estranged from the natural world inhabited by our parents or grandparents?

Charton, a chartered accountant who packed up his career in finance seven years ago to embark on a new path as a storyteller and historian, has rekindled some of the passion that animated Player and Ntombela to establish the Wilderness Foundation Africa, a body dedicated to the stewardship of some of the last remaining patches of “African wilderness”.

Narrating their story in Durban on 23 September, Charton recalled how Player, a mine engineer’s son, met Ntombela (several years his senior) when he joined the former Natal Parks Board as a relief ranger in the early 1950s in iMfolozi Game Reserve — one the oldest game reserves in the world and the last redoubt of the southern white rhino species.

Ntombela, the head of the game guard force, “had the bearing of a warrior” and only spoke isiZulu. Whenever he travelled, Ntombela carried with him a small, three-legged cast-iron cooking pot to prepare his meals — including during his trip to a World Wilderness Congress in Scotland.

Despite the age and cultural chasm, the pair formed a strong bond that lasted nearly 40 years.

Both men led the first wilderness trails into iMfolozi’s specially zoned 12,000ha wilderness zone (the first of its kind in Africa, later expanded to cover 32,000ha). Both were also members of “Operation Rhino”, a massive project to shift white rhinos to other reserves across South Africa and other parts of Africa from the 1960s onwards.

Ntombela died in 1993 (aged over 90), followed by Player in 2014 (at 87). But before he died, Player established the Magqubu Ntombela Foundation in honour of his mentor and wilderness compatriot.

On the foundation’s web page, Player describes some of the time they spent together and the many discussions they held in the wilderness.

At one such campfire meeting in the late 1960s, they agreed on the need to set up an organisation to safeguard the unique, wild character of iMfolozi and other similar areas across the continent. That was the beginning of the Wilderness Foundation Africa, a body that would “acknowledge and honour the web of relationships, the interconnectedness between wildlife, wild places, human beings and the urban environment”.

“The vision was for wilderness areas to become a font of spiritual inspiration and a source of nurturing for future generations. There are many archetypal echoes in wilderness: the prophets of all the great religions, and many lesser-known ones, have gone into the wilderness to be alone and to ponder and meditate, and have returned to preach the word of God as it distilled in their souls in the inner stillness of sojourns in wild and lonely places.”

Fifty years after its formation, the foundation is now headed by Andrew Muir, who took over the reins 22 years ago and moved its headquarters from Durban to Gqeberha.

Over this period, the foundation has taken more than 85,000 young people from disadvantaged backgrounds on wilderness trails while raising several million rands for rhino conservation and mounting a programme in Vietnam to reduce consumer demand for rhino horn.

But is the original concept of “wilderness” still relevant in South Africa today?

This is one of the big questions raised by conservationist Paul Cryer in his Master’s thesis dissertation in 2009.

Cryer, who spent the first 15 years of his career as a trails officer for the Wilderness Leadership School in the iMfolozi, iSimangaliso and uKhahlamba Drakensberg parks, says this question presupposes that wilderness and environmental protection have both value and a finite quality in a modern society focused on economic development.

The question remained especially relevant in a society such as South Africa due to its legacy of colonialism and apartheid because the early concepts of wilderness protection were imported mainly from the United States or heavily influenced by romantic Western notions of an untouched African wilderness.

The 1964 United States Wilderness Act, for example, emphasised the need for human exclusion from these areas by stating that: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognised as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Cryer suggests that this emphasis on human exclusion, combined with the misperception that wilderness is “a blank canvas which humanity has not yet blemished”, had created ideological and political tension, especially in those parts of the world where the wilderness concept had been imported.

This included sections of the iMfolozi wilderness area from which local communities had been expelled to create a refuge for rhinos and other wild animals from 1897 onwards.

As a result, says Cryer, the value of wilderness as a product of rarity was seldom perceived by indigenous or local peoples.

“In such light, the cause of wilderness looks doomed. Yet, despite its early justifications becoming eroded or being deemed politically incorrect, the legacy of wilderness has re-emerged with modern, scientific and liberal justifications.

“Once its meaning shifts beyond a quaint preservation of an idealised un-peopled landscape trapped in time, the broader relevance of wilderness in the 21st century may unfold along with ‘some untapped allies’ from the developing world.”

Cryer also sees hope that the previous isolationist and exclusive definition of wilderness is being redefined or revisited by various scientists, sociologists and philosophers to explore a more liberal and inclusive definition.

“Such thinking produces exciting implications for managers of wilderness areas because it implies that they are managing land with additional values that modern society is only beginning to appreciate.”

This has two implications which may not sit well together, he suggests. First, the management of the emerging concept of wilderness has to include new and emerging views, as well as those previously excluded.

Second, the mechanisms used to manage wilderness have evolved from a previous way of thinking. Until reformed, they will still retain language and applications inappropriate to a more inclusive concept of wilderness.

Caution and respect

Cryer suggests that in navigating such debates, it will be crucial to proceed “cautiously and respectfully”, without the imposition of a rigidly desired outcome.

“Surrounding communities have voiced their desire to derive direct and indirect benefits from what is perceived to be the cash cow of Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park’s ecotourism potential.

“Wilderness will not receive approval from the community as an island of exclusion unless the community, through participative management, enacts the exclusion themselves and has the opportunity to derive benefits from the surrounds.

“Further modification of the principles of wilderness management is therefore necessary. These modifications must, paradoxically, include greater community involvement and the intrinsic rights of nature to truly reflect 21st-century wilderness values held by the developed and developing worlds.”

The logic behind this course of action was that decisions made in a participative manner are not only likely to be better but also less likely to be contested and more defendable when they are contested.

Developed world excesses

Cryer notes that the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha has linked wilderness preservation with the developed world’s response to its excesses.

These excesses have not only been instrumental in creating the impending global environmental crisis (including the decimation of the planet’s wild areas) but have also created the divide between the world’s rich and poor.

Because the “have-nots” of the developing world were victims of imperialism, they had little connection with the cause of the problem. They, therefore, had little empathy for one of its solutions — further human exclusion in the form of wilderness.

In a responding paper published in 1990, American conservation politics writer David Johns agreed partly with Guha’s criticisms but disagreed with suggestions that wilderness protection was untenable or incorrect as a global strategy for environmental protection.

Cryer says the main point raised by Johns is that regardless of the imperialist or elitist origins of the wilderness concept in the 19th and 20th centuries, wilderness still has “a brutally apparent social relevance to both the developed and developing worlds in the 21st century: it is an ecological necessity”.

And yet, as this debate rages, Cryer points out that wilderness areas across the world continue to shrink or become further degraded by the relentless expansion of agriculture, mining and other economic development — and that in South Africa, the amount of land designated as “wilderness” was yet to reach 1% of the country’s surface area.

This story was first published by The Daily Maverick’s Our Burning Planet.