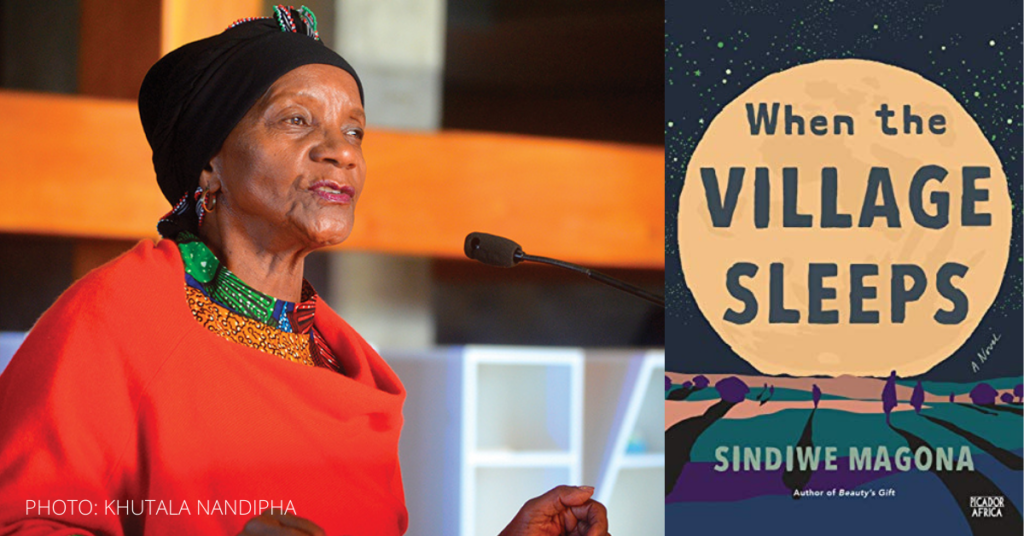

When the Village Sleeps

By Sindiwe Magona

Picador Africa (imprint of Pan Macmillan South Africa) 2021

Review by SAM NAIDU

At a time when national and global morale is at an all-time low, is a novel such as When the Village Sleeps an appropriate read?

Well, it is for the reader who does not seek the escapism of an exotic setting, or the comforts of larger-than-life characters and a far-fetched plot.

What this novel offers is a simple, yet gripping and edifying tale about ordinary characters in a world we recognise as our own. Magona does not hold her punches when it comes to criticism of this setting. She offers a stark and honest portrait of a country afflicted by the worst social ills: poverty; unemployment; crime; state corruption and incompetence; and, teenage substance abuse and pregnancy.

Harsh criticism is leveled at the powers-that-be who have created this catastrophe for all of South Africa’s citizens, but more especially for the poorest and most downtrodden. Yet, in the midst of this bleak landscape there are characters like Khulu and Mandlakazi, women who rise above their circumstances through effort of will, or because of their liminal positioning between the material and spirit worlds, and who help and inspire others with their courage and dignity.

When the Village Sleeps offers a tragic and hopeful tale of four generations of women contending with the particularly harsh challenges of life in contemporary South Africa. It uses these deeply-etched characters, mainly Khulu, her granddaughter, Busi, and her great granddaughter, Mandlakazi, to explore iniquities and injustices faced by the most oppressed category of the population – the poor black woman.

Interestingly and effectively, the narrative also uses the voices of the ancestors (“the Old”) in the form of songs, poems or lyrical prophecies. With this form of intertextuality, Magona evokes and affirms African spirituality. The repeated utterance of the sacred greeting “Camagu!” animates the narrative with a positive energy that serves as a counterpoint to some of its grim subject matter.

Perhaps most significant for the South African literary canon, this novel is multilingual, drawing on the works of A.C. Jordan and S.E.K. Mqhayi to seamlessly intersperse the English with isiXhosa. In many ways, this is a ground-breaking novel because of its syncretic style and careful blending of universal, timeless, as well as pertinent, local and contemporary themes.

Magona’s prose shifts from oral storytelling mode to pertinent political commentary and back again. The voice of the narrator describes the dystopian scenario of South Africa in the grips of the Covid-19 pandemic:

But soon strident voices were raised regarding the chicanery of the government employees. Cadre deployment made daily headlines as money went into the pockets of corrupt officials. The hungry starved as food rotted in warehouses while bureaucrats squabbled, or food parcels were used as bribes for votes, or were simply stolen. Tenderpreneurs splurged on luxury cars while nurses fought for masks and patients for oxygen in hospitals laid waste by a terrible pandemic. (305)

The voice of the ancestors is equally reproachful:

See what you grow!

Lines of beggars

Lines of dispirited, hungry,

Downtrodden by and with your help

What help is that which nails one to poverty?

Disaster after disaster

– GRAFT –

The poor robbed blind

Robbed by civil servants they trust … (306)

When the Village Sleeps is not just a litany of depressing and abject scenes peppered with poetic polemic. Rather, through carefully rendered characterisation and setting and skillful manipulation of the plot, themes such as poverty and the need for self-sufficiency are engagingly explored. We are told that “what government help does for the poor is cement them in poverty” (307). The Child Support Grant is strongly criticised for creating dependency and apathy. Through the use of wry humour, recognisable real political figures are parodied or caricatured, such as the duplicitous and expedient Deputy Minister of Women, Children and People Living with Disability, who earns a fortune through “amaqithiqithi” (250).

Magona is particularly adept at evoking the theme of hybridity. In the figure of Khulu, a noble and morally scrupulous matriarch, a synthesis of indigenous religion or spirituality and Christianity are embodied. Khulu exhorts her family members to preserve indigenous cultural practices and to adapt them to contemporary contexts e.g. ukuthombo for girls and ukwaluka for boys (initiation rituals). When questioned about traditional social mores for women, Khulu answers “‘The same as for men. Most are in the Bible. Many more are in the tales of our forebears, the stories we were told growing up.’” (282). In this way, the novel also serves a didactic or aetiological function.

The novel is divided into three sections, with the first and thirds sections set in Kwanele, a township within the city of Cape Town. The middle section is set in the Eastern Cape. At first Magona’s urban-rural binary seems too simplistically pastoral but as the plot unfolds and characters move between the two locations, the peaceful village of Sidwadweni, ancestral home of Khulu, is also seen to be tainted by wider social and political ills.

Part One focuses on Busi, who is a neglected and fatherless child, growing up in the dangerous, impoverished township of Kwanele. Khulu tells us that “there is NO excuse for fatherless children, a plague in our country right now” (294). Part Two shifts to the rural Eastern Cape, and initially there is a clear birfurcation between the gritty urban life in Kwanele and the idyllic rural life in Sidwadweni. It is not long before it is revealed that this village also contains evidence of the government’s mismanagement and venality, in the form of failed agricultural projects.

Part Three sees the main characters return to Kwanele, and the focus is now on Mandlakazi, the granddaughter of Khulu. Mandlakazi is an extraordinaory character, heroic like her great grandmother, but possessed of metaphysical powers which enable her to function, even as a child, as a visionary leader and prophetess. It is perhaps not accidental that she reminds the reader of notorious nineteenth century Xhosa prophet, Nongqawuse. Unike Nongqawuse, however, in the face of adversity, Mandlakazi advocates for the growing of crops and the nurturing of self-esteem and community. She is also a champion for the rights of differently abled people. Inscribing, too, a strong feminist theme, When the Village Sleep creates a matriliny extending from Khulu, through Busi to Mandlakazi. Mandlakazi’s strength and insight are attributed to lessons learned from Khulu, as well as to the ancient wisdom of the Ancestors – “As her great-grandmother had always known, it is in service to others that we truly grow” (255).

While unrelenting in its criticism of the current government, this narrative is engrossing and entertaining, enabling the reader to become invested in the main characters. There is a great deal to enjoy about this novel, not least of all its lyrical story-telling mode and its refreshing honesty. For any reader, local or foreign, Xhosa or not, this is an eye-opening, affirming text that reminds us, at a very dark time in human history, “to live a life that contributes to the life of a village; a life that destroys nothing and no one; a life that brings joy, help, and grows or encourages all things good in life” (282).

- Professor Sam Naidu lectures in the Department of English at Rhodes University.