THE FIRST ALLISTON (BULLY) KOHL MEMORIAL LECTURE DELIVERED BY LEX MPATI ON 12 MAY 2017 AT THE CITY HALL, GRAHAMSTOWN

I wish to thank the Mawarian Alumni Association and its management committee for inviting me to deliver the first lecture in memory of the life of Alliston Kohl, affectionately known as ‘Bully’. I am honoured by the invitation and privileged to have been nominated and appointment as the first honorary President of the Mawarian Alumni Association. I must confess, though, that I first made sure that the honorary President has no duties to perform before I could accept nomination. And, something that I found very attractive: in terms of clause 14.1.2 of the Association’s constitution the honorary President is exempted from paying membership fees.

Alliston Kohl, (to whom I shall henceforth refer as ‘Bully’), was born in Grahamstown on 24 April 1968, the son of Mr Robert Kohl and Ms Cecilia Kohl (deceased). He attended George Dickerson Primary School in Grahamstown, where he passed Sub-standards A and B and Standard 1. He proceeded to Good Shepherd School where he spent the next four years as a learner, passing Standard 5 in 1981. Thereafter he joined Mary Waters High School where he passed Standard 6 at the end of 1982.

Most of you will recall the student uprising that broke out in Soweto on 16 June 1976, when learners protested against the forced introduction of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in schools, alongside English. Despite attempts by the government of the day to brutally suppress the protest movement, activism among learners grew and spread around the country. Organisations such as the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) and the Azanian Student Organisation (AZASO) were founded in 1979 as national organisations. COSAS was established with the stated aim of representing the ‘interests of Black school students’, while AZASO was founded as a replacement for the South African Student Organisation (SASO), which had been banned on 19 October 1977. SASO’s operations were concentrated mainly at tertiary institutions. Under COSAS learners throughout the country staged a variety of resistance tactics such as boycotts and strikes throughout the 1980s. Their aim was to conscientise students and the wider community to the repressive nature of the education offered them by the apartheid regime and to participate in the drawing up of an education charter for the future. For the benefit of the younger generation, I need to mention that at that time South Africa, excluding the homeland areas, had four education departments, which were the departments of the House of Assembly (for Whites), the House of Delegates (for Indians), the House of Representatives (for Coloureds) and the Department of Education and Training (for Africans). I do not like these race tags, particularly in respect of those who are not white, but since the Constitution recognises our diversity[1] allow me to use them for present purposes. The inferior education system which had been introduced Africans by the racist government of the National Party in April 1955 was known as Bantu Education. I am informed that learners at Mary Waters were eager to join COSAS but, realising that parents, who had been against the boycotts and strikes organised under the banner of COSAS, would not approve, they opted for the formation of another movement, the Grahamstown Youth Movement. Learners’ demands had by now been expanded to include the call for the release of Nelson Mandela from prison and for a free and democratic South Africa, from which came the famous slogan: ‘Freedom now and education later’.

Mr Kohl (senior) informs me that because Bully was harassed constantly by the security police they, as parents, decided to send him to John Bisseker High School in East London where he passed Standard 8 in 1984. He returned to Grahamstown and the following year (1985) he once again registered with Mary Waters for his matric.

On 12 May 1985 I attended a funeral service at the J D Dlepu Stadium in Joza Township, Grahamstown. It was the funeral of a young man named ‘Boy-boy’, who had been shot by a security officer. A big number of mourners attended while some police trucks (commonly known as ‘caspers’ or ‘hippos’) were parked at strategic vantage points around the stadium. After the service the cortege exited the stadium to follow a set route to the Tantyi Graveyard. I was still inside the stadium when I heard shots being fired. It sounded to me as if the shots came inside the stadium, but I heard either on the same or the next day that yet another young man had been a victim of a police shooting after the procession had left the stadium. That young man was Bully.

According to Mr Tyron Austin, a former Mary Waters learner, he and his two younger brothers Devron and Hyron, together with Bully, Eldrid September (Pink-eyes), ‘Beans’ Mahapi, Peco Prince (deceased), Charles Wessels, Reggie Waldick and others, had walked to Joza and attended the funeral. When the procession left the stadium for the graveyard he and his companions formed part of what he calls the second group of young people following the hearse. When the got to about the western entrance to the stadium the second group broke away and took a side street. Although he did not know at the time why the breakaway group took the side street, I assume that the leaders of the group probably wanted to get to the graveyard sooner than the rest of the procession. Soon after they had entered the side street the group was met by gunfire from ahead. The group turned and ran back towards the rest of the procession. Tyron says that as they ran back the firing continued and he could hear the swishing sounds of projectiles passing above his head. He then noticed that Bully, who was running ahead of him, was losing his step. He grabbed hold of him and helped him along. Once off the side street they ran into the premises of a certain house near the stadium. He had by then noticed that Bully had been shot in the back of his head and was getting weak. At first he left he left Bully in an outside toilet (the only toilet, of course), but before going out to look for a vehicle so as to take him to hospital he took Bully out of the toilet and placed him on the floor of the house on the premises with the owners; consent. He managed to persuade the owner of the property next door who had a motor vehicle to convey his companion to hospital. On the way to hospital they were delayed at a police roadblock for what Tyron Austin thought was about 15 minutes before they could get to Settlers Hospital, where it was confirmed that Bully was no more. During his testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, sitting in East London, Mr Kohl said that Bully had been a member of the Student Representative Council at Mary Waters.

Bully’s demise was reported at the Grahamstown Police Station to a senior police officer by Mr Kohl personally, but, according to him, no inquest was ever held to establish which security officer was responsible for the shot that prematurely ended his son’s young life.[2]

Just over two months after the tragic passing of Bully the state responded to the growing resistance against its repressive laws, strengthened by the formation of the United Democratic Front in 1983, by declaring a country-wide state of emergency on 21 July 1985. Regulation 3 of the regulations made in terms of the Public Safety Act[3] and gazetted[4] simultaneously with the declaration of the state of emergency, authorised a member of a force to arrest, without a warrant of arrest, or cause to be arrested, any person whose detention is, in the opinion of such member, necessary for the maintenance of public order or the safety of the public or that person himself, or for the termination of the state of emergency. The arrested person could then be detained, without trial, under a written order signed by any member of a force, for a period not exceeding 14 days.[5] That 14-day period could be extended by the Minister of Law and Order in terms of reg 3(3), which read:

‘The Minister may, by written notice signed by him and addressed to the head of a prison, order that any person arrested and detained in terms of ss (1) be detained in that prison during the further period mentioned in the notice.’

The Minister could accordingly extend the initial detention of a detainee for a period until, for example, the date upon which the state of emergency would be lifted, as he did in Minister Gugile Nkwinti’s case.[6] These draconian regulations made it possible for the state to detain political activists, young and old, for lengthy periods of up to three years without ever having been charged with any offence. Some, if not all of the members of the Grahamstown Youth Movement mentioned above and who were with Bully on that fateful day were among those who suffered the injustice of detention without trial: We salute them!

I have tried to tell the story of Bully’s life extensively not for opening up old wounds that might already have healed, but rather for the younger generation to know that someone had to die for them to have the privileges they now enjoy and not to forget our painful past.

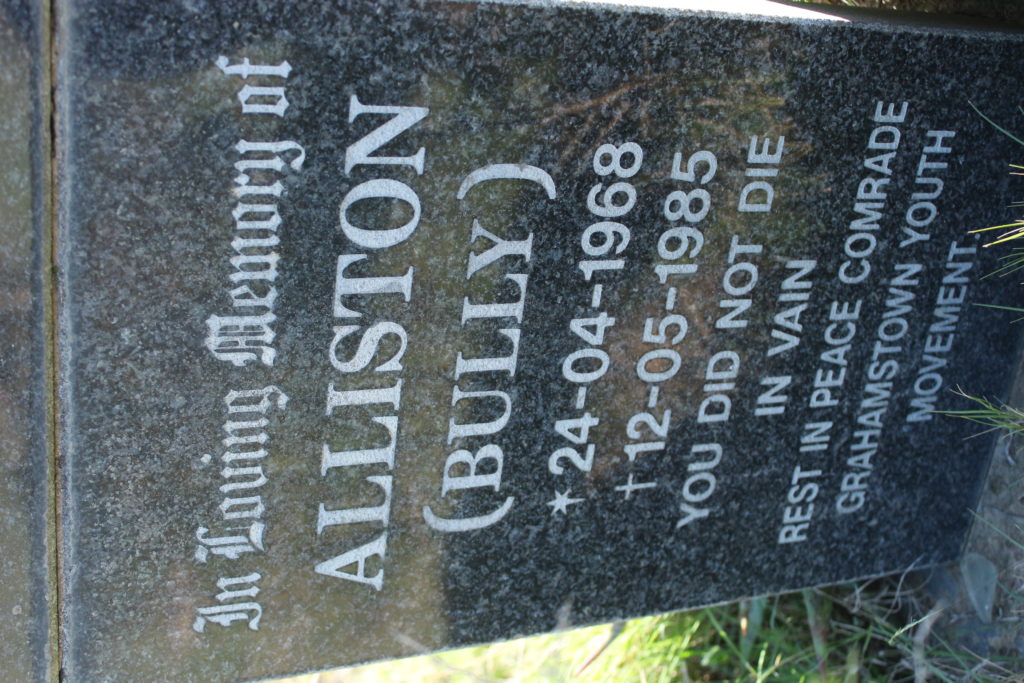

Last week I had occasion to visit Bully’s grave with his father. The apt inscription on his tombstone reads:

‘YOU DID NOT DIE IN VAIN. REST IN PEACE COMRADE.

GRAHAMSTOWN YOUTH MOVEMENT’

Indeed Bully and others before and after him did not die in vain. Nor did those who suffered the indignity of detention without trial suffer in vain. The freedom they demanded was ultimately delivered on 27 April 1994, when all South Africans eligible to vote, freely exercised their vote. As to the education system, the multiple education departments that existed in 1985 were at least brought under one ministry until recently split into basic and higher education. However, the high number of cases of a violation of the right to basic education that find their way to the courts is disconcerting. These cases relate to failure, mainly by provincial education departments, to deliver books timeously or at all, or failure to appoint teachers.

I have tried to tell the story of Bully’s life extensively not for opening up old wounds that might already have healed, but rather for the younger generation to know that someone had to die for them to have the privileges they now enjoy and not to forget our painful past. (Many people died, but just bringing it closer.)

Of Bully and other heroes of the struggle for our liberation the preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa[7] declares:

‘We, the people of South Africa, recognise the injustices of the past’ and ‘honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land’.

The preamble continues with a commitment to –

‘Heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental rights;

Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person; and

Build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations.’

The society to be established was to be built on the foundation of the values entrenched in section 1 of the Constitution, which include human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms, non-racialism and non-sexism, and a multi-party system of democratic government, to ensure accountability, responsiveness and openness. Before the transition to a democratic dispensation our society was divided was unequal and divided along racial lines and where discrimination on the basis of race, gender and class was the order of the day.

If the Constitution is a bridge away from a culture of authority; it must lead to a culture of justification, where every exercise of power is expected to be justified, in which the leadership given by government rests on the cogency of the case offered in defence of its decisions, not the fear inspired by the force at its command.

In its postamble the interim Constitution[8] declared that it provides ‘a historic bridge between the past of a deeply divided society characterised by strife, conflict, untold suffering and injustice, and a future founded on the recognition of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence and development opportunities for all South Africans, irrespective of colour, race class, belief or sex’. Professor Ettienne Mureinik commented as follows on this historic bridge:

‘If this bridge is successfully to span the open sewer of violent and contentious transition, those who are entrusted with its upkeep will need to understand very clearly what it is a bridge from, and what a bridge to.’[9]

He went further to explain that the bridge was from a culture of authority, where Parliament was elected only by a minority, and taught the doctrine that what Parliament said was law, without a need to justify even to those governed by the law. He said if the Constitution is a bridge away from a culture of authority; it must lead to a culture of justification, where every exercise of power is expected to be justified, in which the leadership given by government rests on the cogency of the case offered in defence of its decisions, not the fear inspired by the force at its command. The new order, he said, must be a community built on persuasion, not coercion. I add, in relation to the culture of justification, that if every exercise by the state of public power must be justified in the new order, then the state’s failure to do what it was supposed to do must also be justified. (See cases involving failure by education authorities either to appoint teachers to deliver school books.)

The vision of our Constitution and the Bill of Rights entrenched therein is the transformation of what had been a divided and unequal society to a united citizenry with equal opportunities afforded to all. As was said by acting Chief Justice Moseneke, the Constitution has a transformative mission.[10] Albertyn and Goldblatt say this about transformation:

‘We understand transformation to require a complete reconstruction of the state and society, including redistribution of power and resources along egalitarian lines. The challenge of achieving equality within this transformation project involves the eradication of systemic forms of domination and material disadvantages based on race, gender, class and other grounds of inequality. It also entails the development of opportunities which allow people to share their full human potential within positive social relationship.’[11]

The Constitution enjoins the judiciary to uphold and advance its transformative mission. Our courts have been clothed with the authority to formulate and implement measures that are directed at remedying past discrimination. But in doing so, due care must be taken, particularly when substantive equality is sought to be achieved, to ensure that the dignity of others is not unduly invaded.[12] Chaskalson CJ made the following observations about the transformation project:

‘The difficulties confronting us as a nation in giving effect to these commitments are profound and must not be underestimated. The process of transformation must be carried out in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution and its Bill of Rights. Yet, in order to achieve the goals set in the Constitution, what has to be done in the process of transformation will at times inevitably weigh more heavily on some members of the community than others.’[13] [14]

In September 2014 the Constitutional Court observed that our society ‘has done well to equalise opportunities for social progress, though past disadvantage still abounds’. I’m inclined to agree. The other day a member of the panel of accountants that participated in a television discussion on the state of our economy and what can be done to rescue the situation was prepared to admit that ruling party has had some successes in government. He mentioned that before the present government took over our economy was growing and this enabled us to invest in infrastructure and build houses for the poor, thereby creating jobs; payment of social assistance could be extended to cover child grants, etc.

I also agree that past disadvantage still abounds. Poverty and unemployment among black communities pose a serious risk to the country. A post on the Mawarian Alumni Association website reads:

‘Today many people are enjoying the fruits of their battles but few seem to care what happened to those who sacrificed their education and lives for the cause. Some, like Bully, paid with their lives, but I can only imagine the frustration of those who are still among us must be suffering when they witness what is happening to their dream. (OUR DREAM!!!).’

This illustrates the resignation or despondency that occupies the minds of many people. Our beloved country is in a crisis because of bad decisions. In a recent graduation speech the vice-Chancellor of Rhodes University, Dr Sizwe Mabizela, observed that-

‘Many in our society feel trapped in a state of powerlessness; in a state of hopelessness and in a state of helplessness.’

But he said that ‘we cannot afford to lose the hope that sustained us in the dark days of apartheid’ and that ‘we cannot afford not to imagine a better society and a better world than the one which we pray we inhabit temporarily’.[15]

I concur!

The significance of the formation and subsequent activities of the Grahamstown Youth Movement was that although they were conscious of the fact that the education offered at Mary Waters was superior to Bantu Education (at least I thought so when I was at Mary Waters) they risked the wroth of their parents in order to join the call for the scrapping of inferior education. In doing so they stayed true to the call made by Bantu Stephen Biko back in 1971 when he spoke about black solidarity. He said that what we should at all times look at is the fact that we are all oppressed by the same system even though we are oppressed to varying degrees. The one criterion that must govern us, he said, is commitment.[16] I suggest we rise, unite and take part in the discussions taking place around the country on its and our future.

In closing, let me once more quote the Vice-Chancellor of Rhodes:

‘Our country is in desperate need of quality leadership: good leadership, caring leadership, compassionate leadership, bold and courageous leadership, moral and ethical leadership; a leadership which, in the words of Eleanor Rooseveldt, does not only inspire confidence in people but one that inspires people to have confidence in themselves; the kind of leadership which-

“is not a function of material wealth, high office or status, or bestowed by a degree or qualification, but one that must be earned through ethical conduct, impeccable integrity, visionary endeavour, selfless public service and commitment to people and responsibilities.”’[17]

So, as he says, choose your leaders with wisdom and forethought.

I thank you!

[1] See the preamble to the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

[2] The name of a specific security officer has been mentioned, but no judicial process was held to confirm it.

[3] Act 3 of 1953.

[4] Proc R121 published in Government Gazette 9877 of 21 July 1985.

[5] Reg 3(1) and (2).

[6] Nkwinti v Commissioner of Police & others 1986 (2) SA 421 (E)

[7] Act 108 of 1996.

[8] Act 200 of 1993.

[9] Ettienne Mureinik: A bridge to where? Introducing the interim Bill of Rights: South African Journal of Human Rights, 1994 vol. 10 p31.

[10] South African Police Service v Solidarity obo Barnard 2014 (10) BCLR 1195 (CC) para 29.

[11] Albertyn and Goldblatt: Facing the Challenge of Transformation: Difficulties in the Development of an indigenous Jurisprudence of Equality (1998) 14 SAJHR 248 at 249.

[12] South African Police Service v Solidarity obo Barnard 2014 (10) BCLR 1195 (CC) para 30.

[13] Bel Porto School Governing Body & others v Premier, Western Cape & another 2002 (3) SA 265 (CC) para 7.

[14] See e.g. South African Police Service v Solidarity, above fn 12.

[15] Vice-Chancellor’s Welcome Address, 2017 Graduation Ceremonies.

[16] The Definition of Black Consciousness by Bantu Stephen Biko, December 1971, South Africa.

[17] Ibid.