Book review by Gillian Rennie

my mother, my madness by Colleen Higgs (published by Deep South)

Several themes surface in Colleen Higgs’s chronicle of her mother’s last years. There are those any daughter might recognise (the bond of loyalty, the bondedness of reality) and there are those anyone who has witnessed a decline towards dementia would recognise (irascible dishevelment, irrational attachments). This is unsurprising, considering the layered and complex emotions provoked by any and all of these.

But there is one thread weaving through my mother, my madness, through these diary entries, these years, these lives, stitching them together even while their seams loosen. It is the thread which threatens to throttle not only the daughters of mothers; it is the emotional fabric of children everywhere and their parents anytime. How tightly do I hold on? How carefully do I let go? In fact, how do I even begin to let go? The answer is, as Higgs notes on 7 October 2009, “an odd concoction of love, guilt, duty, anger, resentment, longing”.

Although Higgs’s prose is spare and does not call attention to itself, it nevertheless offers metaphoric richness like plump raisins in a light dough for readers seeking depth of flavour. This is just one way my mother, my madness is deceptive: its apparent simplicity carries complex freight. One metaphor that moved me is the recurring observation – now exasperated, now mystified, now matter-of-fact – that yet another pair of nail clippers is missing.

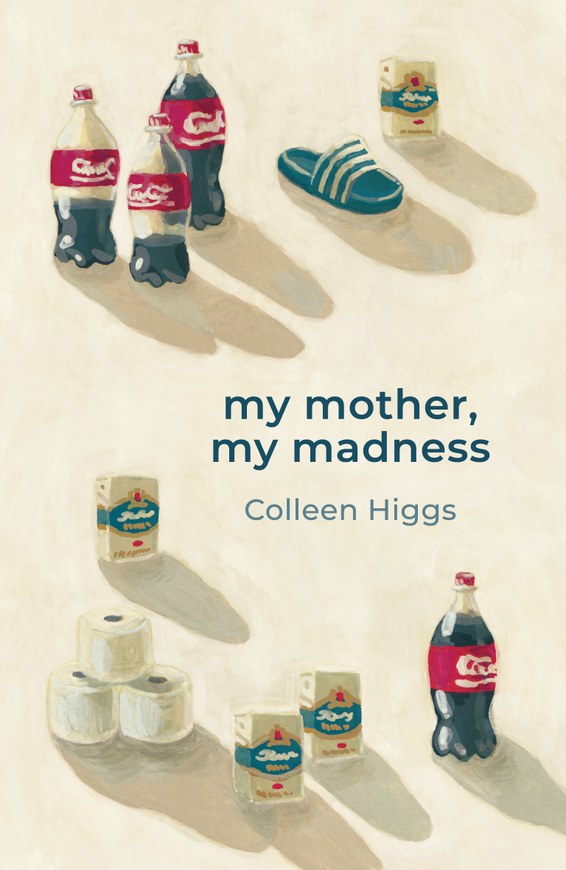

These disappearances are mentioned in passing, often enough to notice but not nearly as often as the mother demands Coke or cigarettes or toilet paper all in boggling quantities. These three most frequently requested grocery items quickly constellate into a shadow for both daughter and reader. So the recurring disappearance of nail clippers becomes comforting – a signal that a daughter knows she needs the right tool if she wishes to trim dead matter from her life. my mother, my madness began life as a secret blog as Higgs wrote her way through her mother’s last 10 years. Edited and now in book form, these entries become a threnody for love alive and love absent.

Higgs is candid about her own depression, the value of (the right sort of) psychotherapy, her own parenting anxieties, the ravages of addiction, the debilitation of dementia. But these are just the overt themes she wrestles with in her diary entries. Metaphysically, my mother, my madness is busy with something larger than all of these: ambiguous loss.

A psychic phenomenon first articulated by psychologist Pauline Boss, ambiguous loss refers to something we had and which has not gone exactly but is now not available to us. A child who has disappeared and remains unaccounted for. A soldier who goes to war and does not return home. A parent with dementia.

For Higgs, however, there is more to her ambiguous loss than the decline of her mother towards dementia. There is the matter of a mother’s love. How much can a daughter reasonably hope for? How does a daughter reconcile the suspicion that there was less than she hoped for? How does a daughter be a good daughter to that mother? Even referencing her is shadow work. We encounter her variously as “my mother”, “Sally” and “my mom”. Only once that I noticed did she get to be “mom”.

In the last years of her life, this mother’s carers classified her as a non-compliant patient, one who refuses to take prescribed medication. This development comes as no surprise: she has for decades already been a non-compliant mother.

As Higgs writes on 11 November 2009: “The after-effects of inadequate mothering have a long shadow; it becomes a lifelong condition one has to learn to live with.“

We witness her learning to do this, taking the time it takes.

Eventually, space of another kind opens out in Higgs’s life and she finds herself softening and opening towards this mother. On 15 September 2013, she records an inner peace.

“I do what I have to for her, I don’t take it personally. I find I love her, I remember that I love her.” But peace comes dropping slow and less than a year later a terse entry for 4 May 2014 records: “Drowning quietly… I’m full of rage, desperation.” The shadow, the shadow.

Sally died in March 2017. That’s when Colleen Higgs writes this two-word sentence: Oh Mom. But that’s not when this poignant, slow-moving book ends.

As the founder and publisher of Modjaji Books, Colleen Higgs has been making rain for South African writers and readers for a long time. So it’s a good season when her own words swell the stream.