By LILLIAN ROBERTS

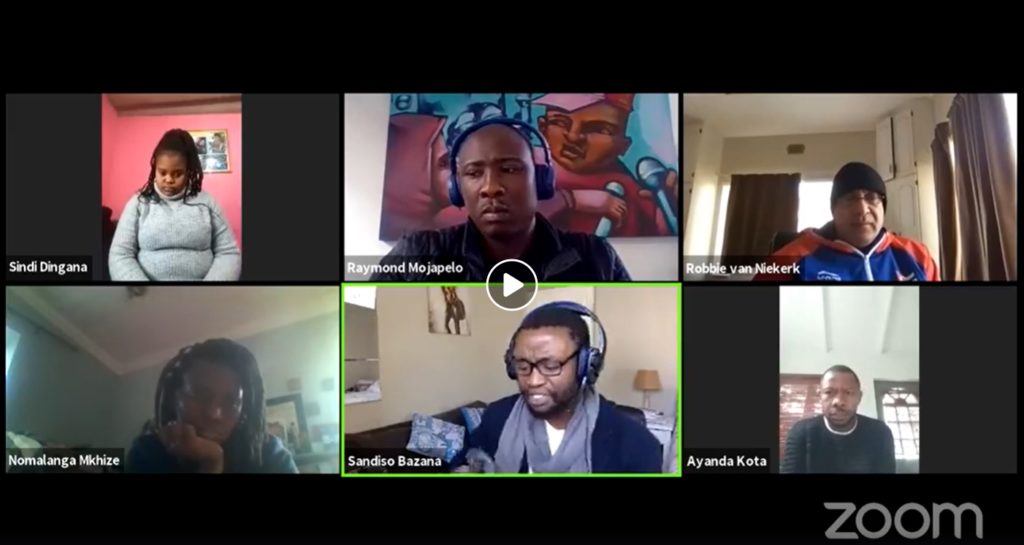

#BlackLivesMatter was the focus of the second in the Makhanda Community Forum series and RMR89.7 Station Manager hosted a discussion on the topic ‘Black lives matter in Makhanda’ with a mostly local panel:

- Sindi Dingana, Manager of Upstart Youth;

- Ayanda Kota, Unemployed Peoples Movement activist;

- Sandiso Bazana, Lecturer and Researcher in Organisational Psychology;

- Nomalanga Mkhize, historian and Makhanda resident;

- Robbie Van Niekerk, Chair of Public Governance at the University of Witswaterstrand’s School of Governance.

A moment of silence was observed for those killed in racially motivated attacks. Sindi Dingana spoke first about how for Upstarters, Black Lives Matter translated to scarce resources and uncertainty about their futures.

Ayanda Kota started from Steve Biko’s definition of Black and quoted Kwame Nkrumah’s thoughts on neocolonialism. Using examples of the evictions in Durban, Cape Town and police brutality in response to student protests at Rhodes, or service delivery protests, Kota argued that in South Africa, the government itself is anti-black.

“The political elite in this country continue, together with the state, to put their crushing knee, and the full weight of state machinery on black bodies. You’ve got a government that is anti-black. You’ve got a state that is anti-black,” Kota said.

Sandiso Bazana referred to his early life in Mthatha, and class-based inequalities. He spoke of the psychological death, the ‘struggle to breathe’ in proximity to whiteness in metropolitan areas, as well as physical death, as in cases such as George Floyd’s.

Nomalanga Mkhize spoke about the power of class.

“Yes I experience racism, all over the place as a black person, but my experience of the racism is somewhat mediated by the fact that I can opt out of having to have direct confrontation, either with the state or with white people, I can buy my way out of it.” She further explained nuances of place, class, gender, and race within South Africa, and Makhanda.

Robbie Van Niekerk spoke about social organising, and the importance of an initiative such as National Health Insurance to address the “faultlines of inequality in our society”.

“16% our of population enjoys 50% our of total health spending, and the 84%, mainly back majority are reliant on the other 50%,” Van Niekerk said. “So that makes us perhaps the most unequal healthcare system in the world…”

Mojapelo directed an audience question to Kota asking whether the government was not in fact doing its best given that it had to negotiate policies such as NHI with “powerful forces” in society and internationally that pushed back.

Kota cited a Corruption Watch episode on the healthcare system highlighting unsanitary conditions, misuse of funds and fraud. Kota said there needed to be more participation by working class local communities for projects such as the NHI. He said the centralised nature of decisions and excessively long implementation time remained a problem.

Responding to the position that the government is anti-black, Van Niekerk disagreed and said rather that “our policies and strategies are not up to the task of fundamentally transforming our society”.

“We have adopted a neoliberal policy framework since the mid-1990s, that… [has]allowed for an elite to be entrenched and has led to the further impoverishment of the black majority masses,” Van Niekerk said. He said mobilisation around #FeesMustFall had put decolonisation on the agenda, and had asked middle class people what privileges they were willing to give up.

Bazana responded said while social policy could be modified, the response of the police and the elite to blackness was generated at a psychological level.

Dingana, asked whether the young people at Upstart spoke about black consciousness, said as tomorrow’s leaders, they were encouraged to voice how they feel and speak about what is important to them on platforms such as their RMR show.

Asked how whites could positively affirm the #BlackLivesMatter movement, Mkhize said, “If you want to be helpful to black people, bring what you have, but don’t try to be the centre of the story.”

Africa had the longest human occupation on the planet with it’s own normative values and traditions.

“You can’t cling on to being white, or cling onto colonial ideas about what Africa is. If you can’t speak an African language, or you’re too terrified to go and make friends with black people, if you can’t do all these things, well then you don’t belong in Africa.”

An audience member asked whether multilingualism in schools was a way to promote diiverse values.

Mkhize’s response was that it was the intention with which language was being used. She cxited the example of some farmers who may speak IsiXhosa fluently, “but he speaks that Xhosa fluently to tell you in your own language that you are black”.

African intellectualism in the community needed recognition, along with the shift away from English being the marker of intellect.

Kota cited Marikana, the Collins Khosa case, state-capture, and 4/10 people unable to afford food daily as evidence of an anti-black government.

Van Niekerk said the problem was framing it as a ‘poverty’ problem and not an inequality problem.

“The problem is lack of distribution of wealth; the problem is lack of distribution of resources, and that who still has those resources, who’s monopolising those resources, and how those resources are distributed.”

He cited the Freedom Charter, including the principle that no one should go hungry. He ended the forum by saying, “I think its about how the new politics of accountability comes on the basis of hopefully a resurgence of new ideas about organisation, and going back to Steve Biko and Matthew Goniwe and reclaiming some of these ideas.”