By POELO KETA

The South African state does not have the funds to adequately cushion the working class during the Covid-19 crisis, according to Professor Lucien van der Walt, director of the Neil Aggett Labour Studies Unit at Rhodes University.

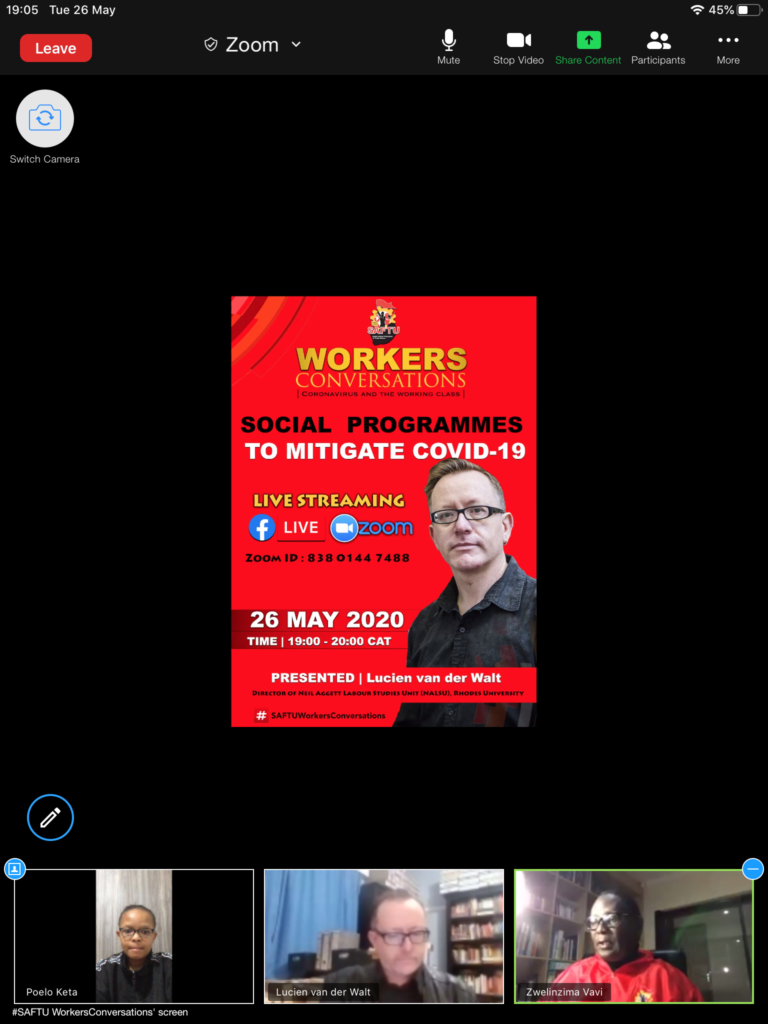

Van der Walt was interrogating the Government’s Covid-19 social security measures at a well-attended online conversation hosted by the South African Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu) on Wednesday.

While the state’s social welfare grants and social insurance measures were intended to cushion the working class, “the state cannot and will not provide welfare on a scale that can emancipate us”, he said.

“This is because the state does not have the funds. It’s in debt, hammered by the economic crisis, hammered by quite a lot of looting, and it has been under huge pressure even before the crisis,” he added.

The social grants, which are non-contributory and needs-based, are very small and focused on people who cannot work. Usually, people who are healthy, unemployed and between the age of 18 and 59 do not get any support. However, during the pandemic, the Social Relief of Distress grant allows those who are not covered by other grants or the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) to receive R350 per month for six months from May.

The supplementation of the grants raises the child social grant (paid to the caregivers of around 12.5 million children) to R740 per child in May 2020. From June to October 2020, child social grants will be decreased to their original amount (R440 per month), but caregivers will receive an additional R500 per month.

A payment increase per caregiver means that instead of a household with three children receiving an additional R1500 per month, they will only get an additional R500 – the same amount as a family with one child.

All other grants will be augmented by R250 per month for six months with a special Covid-19 Social Relief of Distress grant of R350 per month for those who are not covered by other grants or the Unemployment Insurance Fund.

Van der Walt said there had been a problem in the administration of the promised measures. By 25 May, only ten people had received the R350 social relief grant while 2.6 million people had been approved. “This is partly because of corruption, partly because of demoralisation of the state, partly because of what the state is and what it’s fundamentally geared to do and where it puts resources,” he said.

The initial package of relief measures was aimed at supporting households by expanding the Unemployment Insurance Fund, but as economists have shown, about 45% of workers are not eligible for the fund.

Informal sector workers also do not qualify for UIF, and only one in five receives income support through the child support grant. The shortfalls leave at least 8 million people without any form of direct income support.

Currently, many South African’s have lost their jobs and the job security of many others is uncertain. State aid, Van Der Walt explained, will not allow the working class to survive in the current context without going back to work. The state was not able or willing to provide the kind of support that would allow workers to not go back to work.

“We need to think about a return to work and use that return to reactivate union branches, revive union work and safety committees, rebuild relations with communities including running relief schemes like food schemes and enabling community-based organisation,” he said.

There has also been a nationwide crisis of food parcels not being allocated properly and many people living in poverty going to bed hungry. “The food parcel budget for the Eastern Cape is enough to feed 1 in 10 destitute households. There are more than 260 000 destitute households in the province and the parcel system is 250 000 parcels for the whole country. Essentially, if you divide it equally, Port Elizabeth would only get 4 320 parcels a month. It’s very limited,” Van der Walt said.

However, Van der Walt acknowledged that the South African state had committed significant funds to emergency relief for businesses, soft loans, rolling out of JoJo tanks and some spending on online learning for higher education.

“Municipalities are going to get extra money for water supply, sanitation and efforts to expand hospitals, as lockdown does not get rid of infections – it simply slows them so you can buy time.”.

Taken as a whole, however, Van der Walt said that the welfare mechanisms put in place, the social grant expansion, and the social insurance spending is not going to be enough for the working class.

“It’s being administered badly and this exposes the fault lines in our society both around capitalism and the state,” he concluded.

There were more than 50 Facebook participants in the online conversation and 32 tuned in on Zoom, including the vice-chairperson of the Millennium Labour Council, Zwelinzima Vavi, who recently recovered from Covid-19.

When the floor was opened for questions, Warren McGregor asked about the union response to the pandemic.

Van der Walt responded, “At Rhodes, the Fedusa union was actually very vigilant and it prevented the university from opening for a week until there had been proper sanitation. Some unions have failed, but there have been some inspiring examples even from unions that are traditionally quite moderate.”

Ayanda Nabe, the Municipal and Allied Trade Union of South Africa’s (Matusa) media officer and co-ordinator of the National Union of Care Workers of South Africa (Nucwosa) expressed her concern that the profits of big capital remained untouched while employed were paid by government subsidies.

Van der Walt responded, “This is part of the problem with neo-liberalism – we essentially have quite an open economy and it is quite easy to move money in and out the country. So the government and many other governments are worried about what to do with big capital because it can move its money fairly easily.”

Nabe later told Grocott’s Mail: “Big businesses make billions out of South Africans, they exploit South Africans, pay them little money and then they take the profits and transfer them to overseas companies. During this time of Covid-19, our government claims that they will subsidise the poor – but, how do they subsidise the working class? It is a fallacy to believe that their interest is in helping the working class. Their interest rather, is in helping business.”

Saftu will hold another discussion as part of its Workers Conversations series on ‘Education in the context of Covid-19’ on their Facebook page and on ZOOM on 28 May at 7pm.