We are currently celebrating the 150th anniversary of Grocott’s Mail, but there is a good argument to be made that we should in fact be commemorating its 189th year of existence. Grocott’s Mail began publishing as a newspaper on 11 May 1870, but it later took over and incorporated The Graham’s Town Journal which had been in print since 1831.

The Graham’s Town Journal , set up by 19-year-old Louis Henri Meurant, was the first newspaper in the Cape Colony to be established outside Cape Town when it hit the streets on 30 December 1831. The paper thrived as Grahamstown’s economic and cultural importance grew, becoming the second biggest city in the colony with a population of about 5,000 by 1845.

While the rough and tumble of the newspaper business in the early decades of Grahamstown saw printing presses open, close and change hands on a fairly regular basis, in far off England a young printer named Thomas Henry Grocott found himself apprenticed to the Liverpool Mail in May 1854.

When the Great Eastern Star of Grahamstown made him an offer to join the newspaper in Grahamstown he left Liverpool in December 1863. He must have left behind many friends, colleagues and family, but it was the teachers of the Myrtle Street Chapel Sunday School that presented him with books and a beautifully handwritten note dated 2nd December 1863 with the following words:

We understand, that, in a few days, you intend to leave Liverpool for South Africa.

As fellow teachers with you in Myrtle Street Chapel Sunday School in this town, some of us for many years, cannot allow you to leave England without expressing our very earnest desires that every prosperity, temporal and spiritual, may attend you in the future.

As a small token of our very good wishes and esteem, we beg of you to accept the accompanying volumes of “Livingstone’s Travels in Africa”, “Macaulay’s Essays” and “Thomson’s The Land and the Book”, which we trust may interest you, and serve also a remembrance of your old friends.

Thomas Henry worked for the Eastern Star for several years as he got to know Grahamstown and its people. He married a local woman, Eliza Jane Miller, in a ceremony conducted by the Rev Alexander Hay at the Ebenezer Baptist Chapel on Hill Street on 26 July 1866. They eventually had three children: William Ellington, Ida Sarah and Emma Eliza.

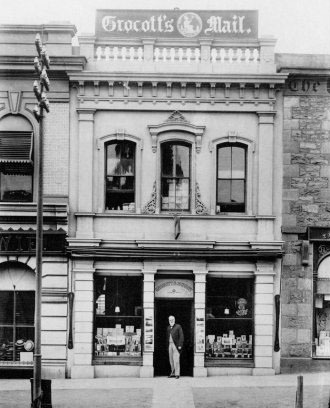

When Thomas Henry felt that he had enough experience under his belt, he set up his own printing business on Church Square in 1869. Grocott’s Steam Printing Works operated from No. 52 High Street where currently the Woolworths retailer runs its commercial operations.

It is interesting to note that Grocott’s Mail, like several similar enterprises at that time, started life in Grahamstown as a printing business and only later expanded into publishing newspapers.

Grocotts Mail is born

On 11 May 1870, Thomas Henry printed the first edition of Grocott’s Free Paper describing it as “An Advertising Medium for Town and Country” – despite the fact that five newspapers, including the Graham’s Town Journal, were already being published in town.

An advertising medium it was, carrying prominently on its front page an advert for: Overcoats, Reefers[1], Wrappers, Inverness Capes[2] and warm winter hosiery. Right at the top of the page was an announcement for a lecture at the Ebenezer Baptist Chapel and the subject of the lecture was “England” with illustrations of Torquay and Liverpool, specially painted for the lecture.

Grocott’s was printed every Wednesday as a free newspaper only until 2 January 1872 when it became the Grocott’s Penny Mail, distributed twice a week on Tuesdays and Fridays. Steam was introduced to power the machines and allowed for increased production.

The editorial for the first edition described the change as “the outgrowth of the Free Paper taking its stand as a regular news-sheet.”

As a news organisation, Grocott’s Penny Mail grew rapidly and was soon being distributed throughout the Cape Colony, the Orange Free State, the Transvaal Republic and to missionary subscribers as far as the Zambezi River.

The editorial said it all, “Everything will be done to make the Penny Mail a complete record of everything important to be known.”

In July 1882, publication of Grocott’s was increased to three times per week – Monday, Wednesday and Friday and it became the first newspaper in the country to publish serialised stories. In August of that same year, Thomas Henry Grocott became a founder member of the National Press Union of which he was President from 1902 until his death in 1912.

In 1892, Richard Sherry, who started at Grocott’s at a very early age and who “displayed acute business acumen”, was appointed partner in the firm and the company became known as Grocott and Sherry. He was an enigmatic figure. Little of him is known other than that his wife (unnamed) died after they had been married a very short while and that he never remarried but dedicated his life to the company until his death in 1931.

The year Sherry became a partner in the business, the printing works moved further down the block from No. 52 to No. 40 High Street.

A massive Industrial Arts Exhibition to celebrate Queen Victoria’s jubilee was held in Grahamstown in 1898. At this exhibition the Grocott and Sherry printing business was awarded two medals of excellence and displayed a pedal powered, state-of-the-art business card printing machine.

Also displayed at the Exhibition was the first linotype machine which was promptly bought and installed in the printing works early in 1899. Thomas Henry Grocott’s only son, William Ellington Grocott was the first person to operate it.

Grocott’s Mail covers war

The South African War, previously known as the Anglo-Boer War, between 1899 and 1902 marked a high point for the Grocott’s Penny Mail. It had the latest equipment and an editor formerly employed by the Times of London to ensure the best quality printing and a war to cover that made it riveting reading.

In September 1899, the newspaper launched ‘special editions’ to cover the war whenever there was news to report, even if it fell outside the normal printing schedule. Grahamstown residents would know there was a special edition on sale if ‘two prolonged shrieks’ were heard from the steam whistle at Grahamstown Roller Flour Mills on Hill Street. It is said that the whistle was audible in a radius of 13 kilometres.

There was a clear need to know what was happening in the country and especially in the Albany region, so people bought newspapers and business was good. As many as five editions per night were printed with the latest war news while a weekly war summary carried telegraphed reports from 18 field correspondents.

Although Grahamstown was firmly ensconced within the British side of the war, not all residents concurred with the way the war being conducted. The town’s two newspapers of the time, Grocott’s Daily Mail and The Journal (previously The Graham’s Town Journal) had very different editorial standpoints that threatened to spill over into the courts.

There were tensions among residents and life was more chaotic than usual as people sent their children from upcountry to the relative safety of schools in Grahamstown and soldiers were constantly on the move.

A devastating fire caused the roof to collapse and severely damaged the front shop of the Grocott’s building but left the printing works largely operational in 1905. It was rebuilt in the following year with new floors, shelving, glass cabinet and windows.

The Grocott’s and Sherry business had secured its position in local community life when it found itself obliged to print a special memorial edition. Disaster struck a train on the Blaauwkrantz Bridge on the line to Grahamstown from Port Alfred on 22 April 1911. Twenty-eight people were killed and 22 were injured when a truck carrying stone to build the cathedral overturned and caused passenger carriages to derail and tumble onto the rocks below.

The rail tragedy had a great impact on the confidence of Grahamstown residents, even though business was generally good.

In the following year, 1912, there were several proposals to celebrate the centenary of Grahamstown, but they were not universally welcomed. There was much debate about a proposal to erect a monument on the spot where Colonel John Graham and Captain Andries Stockenström took the decision to locate the future city of Grahamstown.

The debate was heated and largely played out on the pages of the Grocott’s Penny Mail. Acrimony centred around the design of the monument and the vast amount – two hundred pounds – that the Grahamstown Council would have to pay.

Professor George Cory, who proposed the monument in the first place, thought it was “a most beautiful design” and Dr Selmar Schönland said it would be an “ornament to the town”.

On the other side a rather harsh comment in the newspaper said that it was “The most hideous thing you could possibly put up in any town”.

The monument was built, but it was technically never completed as certain aspects remained to be dealt with later, and never were. The Journal published a special supplement with many photographs of Grahamstown to mark its centenary.

Soon after the muted celebrations, the clouds of war in Europe threw ominous shadows over this British outpost. The turmoil of the Great War drew many young men from their routine lives in Grahamstown to the muddy trenches of the Somme. Too many of them did not return alive.

If the war was an unprecedented calamity for the families of those who lost their lives, it was good for the newspaper business.

Grocott’s Penny Mail grew to eight pages and featured Punch cartoons, war maps and special supplements. But it also carried news of dreadful personal heartbreaks.

A Mrs E.A. Pattison of Sidwell wrote a letter to Messrs Grocott & Sherry explaining that she was sending a block of her sons’ photos that was used in The Cape Times together with a hand-written sketch from October 24, 1914 to October 24 1916 about how her boys, Charles Joseph and Victor Reginald, had fought and lost their lives in Europe. She then asked that their names be added to the Roll of Honour pamphlet.

The War ended and Grocott’s Mail celebrated with Grahamstown, but tragedy was not over.

Returning soldiers brought back with them the so called “Spanish ‘Flu” and about 1 000 people in the Albany District lost their lives – a terrible way to end the first half a century of Grahamstown’s preeminent newspaper publishing enterprise.

[1] Reefer – a close-fitting usually double-breasted jacket or coat of thick cloth

[2] The Inverness cape is a form of weather-proof outer coat. It is notable for being sleeveless, the arms emerging from armholes beneath a cape.

https://www.grocotts.co.za/2020/05/22/consolidation-in-the-second-fifty-years-1920-to-1970/